Jane Austen’s popularity has only continued to grow these past two hundred years—even though the world has changed dramatically, to the point that books written even a few decades ago can seem hopelessly dated. Fans of her novels can site many valid reasons—her razor-sharp wit, her modernization of romance, her unforgettable characters. We may no longer know a barouche from a phaeton…but as much as the details of life change, human nature endures. Austen understood that as richly as any novelist ever has. The clever prose and nimble plots draw readers in, but it’s her deeper insights that make her stories and characters linger so long in the imagination.

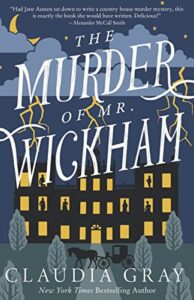

When I sat down to write a murder mystery peopled with Jane Austen’s characters (The Murder of Mr. Wickham), I wondered how quickly the author herself might have seen through the various lies and excuses that surround the crime (as well as the many other secrets that unfold during this fateful house party at Donwell Abbey.) The answer: not immediately, but very soon. Her various villains, antagonists and rogues all manage to deceive the other characters for a while, but when we read through a second time, the clues about their darker inner natures are all too clear. Jane Austen knew whom to look out for.

What is one obvious quality that nearly all of Austen’s rogues have in common? Charm.

Not one of her villains arrives in a black cape, twirling a mustache while making ominous threats. No, every one of them at first appears amiable, attractive, even delightful. John Willoughby of Allenham loves poetry and scenery as much as the sensitive Marianne Dashwood; Mr. Elliott courts his distant cousin Anne with gallantry and wit. Even Austen’s most memorable rogue—the dastardly Mr. Wickham—is at first so courteous and entertaining that no less penetrating a character than Elizabeth Bennet quickly believes even his most outlandish tales about the wrongs done him. When her sister Jane gently points out that they don’t have the full story, Elizabeth protests, “There was truth in his looks.”

But truth is not found in appearances, only in actions: This was a point Jane Austen understood very well and illustrated in every single one of her six novels. Over and over again, the villains are often those most able to delight, beguile, and otherwise deceive those around them.

The female antagonists in her novels are, in fact, some of her liveliest and most engaging characters. Mary Crawford of Mansfield Park may be second only to Elizabeth Bennet in the Austen canon for sheer wit, and she displays finer feelings as well—her regard for the often-neglected Fanny Price is more sincere than self-motivated. Isabella Thorpe in Northanger Abbey may be more transparently ambitious, but she’s both beautiful and winning; even those more experienced than the young Morland siblings can be misled into trusting her.

However, Jane Austen does not portray charm as wicked in and of itself. While charm is often used in her books as a form of concealment, the motives at work are not always nefarious. Also in Northanger Abbey is the wittiest of her romantic heroes, Henry Tilney. He’s debonair, courteous, and gently flirtatious, seemingly unflappable regardless of any trouble around him. Yes, his charm proves to be partly a front—but what Henry is hiding is not some wicked plot but instead the ambition and ill-temper of his father, and the emotional vacuum left in the Tilney household after his mother’s death. Frank Churchill of Emma is even more engaging—far too much so for him not to be concealing something from the characters (and the reader). In that case, Frank is indeed feckless, reckless and somewhat immature…but he means no harm, only hoping to conceal his secret engagement until he has claimed his inheritance and, in turn, his freedom.

Only a small handful of Austen’s antagonists lack charm entirely. They are, without fail, the characters who are not actively working against the heroine but whose personalities create (usually unintentional) conflict. Mr. Collins of Pride and Prejudice has no secret agenda; his desire to marry one of the Bennet sisters may be hilariously misguided, but he genuinely believes himself to be helping the family. He is no plotting schemer, just a awkward, inept young man. Sir Walter Elliott and his older daughter Elizabeth have blighted Anne’s life in Persuasion through their snobbery and coldness, but they do not actively work against her. This would require them taking her into consideration, which they never do. They believe themselves to have saved her from an imprudent match and can’t understand why she doesn’t prefer the more exalted social set they court so assiduously.

So what, then, Austen’s the telltale sign that a character is not to be trusted? Whether a character’s actions match their words. Even minor falsehoods signal that evil—whether great or banal—is at work.

The most famous example of this in Jane’s work comes from Pride and Prejudice, when Elizabeth herself realizes how little of Mr. Wickham’s fine talk reflects his real behavior. When Wickham claims that Darcy has wronged him, he boldly says that he would be glad to face Darcy: “If he wishes to avoid seeing me, he must go.” But when the next ball is held, to which both men are invited, Wickham is nowhere to be seen. At first Elizabeth makes excuses for Wickham’s behavior; only with time and perspective does she realize how anxious he was to avoid the one person who would know him to be a liar.

Isabella Thorpe is also easily caught out. Only somebody as young and naive as Catherine Morland would fail to realize that Isabella’s proclamations of love for James ring hollow, given her frequent flirtations with other men—particularly those with more money. Mr. Elliott in Persuasion may genuinely admire Anne, but not the rest of her family, who he flatters to their fans and insults behind their backs.

Austen’s most sympathetic rogue, Mary Crawford, tells no audacious lies. Her character is almost too open; if she’d dissembled a little more, Mansfield Park might end with Mary’s wedding to Edmund Bertram, not Fanny Price’s. Yes, she glosses over some flaws in her brother Henry’s character, but she doesn’t seem to see this as concealment. If anything, Mary wants to believe that Henry is changed, because she genuinely approves of his potential marriage to Fanny. But it is Henry’s courtship that leads Mary into her one great lie: She pretends to give Fanny a gold chain to wear, an older one she has no use of, when in fact is a gift from Henry. Fanny is horrified when she learns the truth. In that era, such a gift from a gentleman to an unmarried lady was a strong indication that a proposal of marriage would be made—and that woman’s acceptance of the gift was a strong sign that she’d say yes to that proposal. To Mary the fib is harmless, a way of fostering a marriage she thinks would be a fine match for both Henry and Fanny. But the lie entraps Fanny into a courtship she doesn’t want, and a compromising of her dearest principles. Fanny realizes immediately that, although Mary’s heart is not corrupt, her principles are.

So Jane Austen would be too wise to make any snap judgments. She’d watch her suspects closely, evaluating all that they say and weighing it against all that they do. It wouldn’t be long before she saw the differences—and pointed directly at the culprit.

***