You are the servant of two masters. Loyal to one and lying to the other. Life is a performance and you can never leave the stage. Constantly looking over your shoulder to see if you’re being followed. Because when you’re a double agent if the other side sees through the lies, then it’s a bullet in the back of the head.

Webster’s defines double agent as “a spy pretending to serve one government while actually serving another.” Perhaps they should add that being a double might be the most dangerous job in intelligence work and, if spy fiction is any indication, things usually don’t end well.

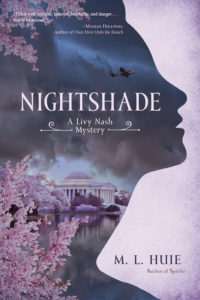

In my book Nightshade, the protagonist Livy Nash, a British spy at the very beginning of the Cold War, is asked to be a double in order to locate her best friend who went missing at the end of World War Two. Before beginning I decided to dip into the trove of fiction and non-fiction double agents and what I found assured me my main character was going to have a rough go of it.

Ben Macintyre is arguably the best writer of espionage non-fiction today. His A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal is an extraordinarily personal account of infamous British defector Philby’s relationship with fellow spy and close friend Nicholas Elliott. Philby’s deception strikes a far more intimate chord as Macintyre explores its impact on Elliott.

But the book I went to first for research is Agent ZigZag: A True Story of Love and Betrayal, his excellent account of charming, enigmatic WW2 British double agent Eddie Chapman. A career criminal, Chapman fled the British police to the Channel Islands in 1939. He was in prison there when the Germans occupied the islands a year later. Hoping to get back to England Chapman offered to spy for the Abwehr, the German secret service. They agreed and had him parachuted into Britain to assist in their sabotage campaign. But ever the opportunist Chapman promptly turned himself into MI5 and offered to spy for them.

Chapman played both sides brilliantly, deceiving the Germans while keeping the British wondering whose side he was really on. He was a professional crook after all, so his handlers at MI5 found themselves constantly questioning his loyalty.

Macintyre’s book is filled with marvelous wartime detail such as how wireless signals were sent, and the individual signatures that let MI5 know Chapman was the actual sender.

Despite his wartime exploits, Chapman landed on his feet. Not only did he survive but Chapman went on to write several autobiographies. His story also inspired the 1966 war drama Triple Cross starring Christopher Plummer.

Fictional double agents don’t seem to fare as well.

If you haven’t read Casino Royale and The Spy Who Came In From The Cold go do that now—right now—because there are MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD.

Ian Fleming’s first 007 novel is notably famous for introducing the world to the cold agent with the license to kill, James Bond. But its most fascinating character is the female spy Vesper Lynd. Besides being hampered with that cumbersome name, Vesper is the first in a long line of damaged women in Fleming’s novels who fall in love with Bond only to meet a bad end. Yikes.

But a second read reveals a woman under duress throughout, for Vesper is a double agent. Bond spends most of the first part of the book complaining that he has to work with a woman. If you can get past that cringe-worthy start then look at the book from her perspective. Vesper seems a perfect ally at almost every moment. Bond dismisses her throughout, but Vesper is just barely keeping it together as she is forced to serve two sides, blackmailed by the Soviets with information they tortured out of her lover, an RAF pilot. Knowing that she will never be free of the spies controlling her, Vesper commits suicide and confesses to Bond in a note.

Vesper’s story teaches us that the constant stress of living as a double often leads to desperate measures.

The Spy Who Came In From The Cold is considered by many to be John le Carré’s finest novel. One could argue for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, but that’s another article. The main character, Alec Leamas, is a veteran and a dedicated agent of Britain’s MI6 obsessed with trapping his East German counterpart, the sadistic Mundt. Control, the head of the Circus, (le Carré’s moniker for Mi6) asks Leamas to “defect” to the East Germans in order to convince them that Mundt is a double agent himself.

Le Carré takes us through Leamas’s performance to convince the East Germans that he is ripe to work for them. Here the master of spy novel reveals the creation of a double, and its innate theatricality. Leamas starts drinking, get fired from the services and begins work at a library where he takes up with a young woman, Liz Gold, who is also a member of the local Communist Party.

Like Bond and Vesper, they too fall in love, and their relationship complicates an already circuitous and dangerous journey for Leamas. And—here comes that spoiler—as with poor Vesper at the end of Casino Royale, Leamas doesn’t exactly ride off into the sunset with his newfound love.

Whether fiction or non, the lot of the double agent is rarely a happy one. As Johnny Rivers sings in “Secret Agent Man,” the odds are you won’t live to see tomorrow.

***