The gentleman thief Arsène Lupin, who is both expert cat-burglar and brilliant detective (as well as a master of disguise), made his debut in the short story “The Arrest of Arsène Lupin” in July of 1905. A year later, author Maurice Leblanc thought, why not feature his genius protagonist facing off with the most famous sleuth of the day, Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes?

As a character, Lupin does not have much in common with Holmes, despite their enormous intellects and penchants for showmanship; if he resembles anyone in British literature, it’s the popular gentleman thief character A. J. Raffles, created by E. W. Hornung (who was, incidentally, Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law) and featured in stories from 1898 to 1909. But both Holmes and Lupin were extraordinarily popular; Holmes, had, in fact, just been brought back by Arthur Conan Doyle, who had attempted to kill him off in 1893. Nearly a decade of mournful, protesting fans led him to publish the flashback novel The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1901-1902, and revive the character altogether with a series of short stories published in The Strand.

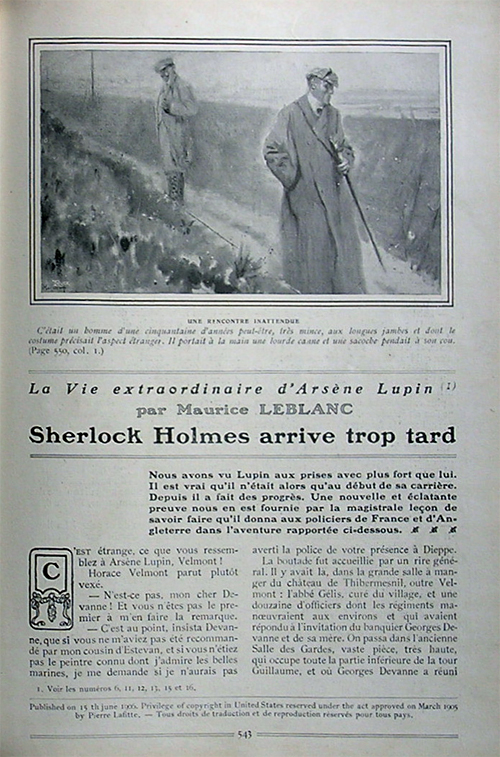

Leblanc no doubt wished to capitalize on this enormous Holmes phenomenon (more than Lupin’s mere creation already had, that is), and published a story entitled “La vie extraordinaire d’Arsène Lupin”: “Sherlock Holmes arrive trop tard” (“The extraordinary Life of Arsène Lupin: Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late”) in the French magazine Je sais tout in June of 1906. In this story, both detectives wind up investigating the same mystery. They discover the same clues, though Lupin gets the better of Holmes towards the end when he steals his watch and gives it back to him with his business card.

Leblanc no doubt wished to capitalize on this enormous Holmes phenomenon (more than Lupin’s mere creation already had, that is), and published a story entitled “La vie extraordinaire d’Arsène Lupin”: “Sherlock Holmes arrive trop tard” (“The extraordinary Life of Arsène Lupin: Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late”) in the French magazine Je sais tout in June of 1906. In this story, both detectives wind up investigating the same mystery. They discover the same clues, though Lupin gets the better of Holmes towards the end when he steals his watch and gives it back to him with his business card.

Since this development had not been authorized by Doyle, according to the Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia, Doyle’s complaints caused Leblanc to change the name of the character. When the story was republished as Chapter Nine in the novel-anthology Arsène Lupin gentleman cambrioleur (Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Thief) his name was rewritten as “Herlock Sholmès.” An English translation of this collection of Leblanc’s stories called him “Holmlock Shears.” Leblanc had also included Watson in these stories, whom he renamed “Wilson.”

Herlock Sholmès made four more appearances in the Lupin canon, all but the last of which appeared in the magazine Je Sais Tout: in La Dame blonde (The Blonde Lady), which was serialized from November 1906 to April 1907, La Lampe juive (The Jewish Lamp), which was serialized from September 1907 to October, L’Aiguille creuse (The Hollow Needle), which was serialized from November 1908 to May 1909, and 813, serialized from March 1910 to May and published in Le Journal.

Through his affable pastiching (fan fiction, might we say?) Leblanc is clear that he has nothing but admiration for the real Sherlock Holmes, and his creator. In The Blonde Lady, Lupin introduces Herlock Sholmès with only the most glowing, and knowing, of presentations:

“He is Herlock Sholmès, that is to say, a sort of miracle of intuition, of insight, of perspicacity, of shrewdness. It is as though nature had amused herself by taking the two most extraordinary types of detective that fiction had invented, Poe’s Dupin and Gaboriau’s Lecoq, in order to build up one in her own fashion, more extraordinary yet and more unreal. And, upon my word, any one hearing of the adventures which have made the name of Herlock Sholmès famous all over the world must feel inclined to ask if he is not a legendary person, a hero who has stepped straight from the brain of some great novel-writer, of a Conan Doyle, for instance.”

Well, as the French might say: l’imitation est la forme la plus sincère de flatterie.

Voila. C’est ça.