The book smelled old. It must have been sitting on the shelves of the secondhand bookstore for a long time before I bought it. The title was enigmatic: With the Italia to the North Pole. What was the Italia? And who was going to the North Pole? The author was just as mysterious. Who was Umberto Nobile?

I was looking for a mystery to solve—and now I had found one.

When I opened the stiff pages of the ninety-year-old volume to try to find the answers, I felt a slight draft on my hand. An equally old and irregularly cutout newspaper clipping slipped out of the book and fluttered to the floor.

The faded headline of the story answered some of my questions. It read: “Bound for the North Pole. Italian’s Big Adventure. First Day’s Thrilling Experiences.” The story was bylined London, April 16, 1928.

As I fumbled with the book, an old map unfolded itself from the back cover to offer another clue: “Svalbard,” it was titled. Suddenly I could hear the throb of zeppelin engines in my ears.

***

Svalbard is a tiny group of dots in the middle of the Arctic Ocean. In Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, Svalbard is described to Lyra, the heroine of the books, as “the farthest, coldest, darkest regions of the wild.” It is a land of “slow-crawling glaciers; of the rock and ice floes where the bright-tusked walruses lay in groups of a hundred or more, of the seas teeming with seals . . . of the great grim iron-bound coast, the cliffs a thousand feet and more high where the foul cliff-ghasts perched and swooped, the coal pits and fire mines where the bearsmiths hammered out mighty sheets of iron and riveted them into armor.”

It was on Svalbard, I now knew, that I would find answers to my last questions. I caught a Boeing from London via Oslo to Longyearbyen, the “capital” of these remote islands. The two-and-a-half-hour flight time in a modern airliner did make the ends of the earth seem closer. As we dragged our bags across the tarmac to the lonely airport terminal building, the icy wind from the North Pole that cut through our down jackets as if we weren’t even wearing them was a healthy reminder of where we actually were. If that didn’t make us realize how far north we had traveled, on three sides of the tarmac strip were mountains covered in snow, their glaciers glinting fiendishly in the April sunlight. At the end of the runway lay the cold, gray, and deadly waters of the Arctic Ocean itself.

Jutting out of the mountainside above the airport was the gray rectangular entrance to what appeared to be a nuclear bunker. My guess was not far off. It was the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a long-term seed storage facility built to stand the test of time—and the challenges of natural or manmade disasters. The seed vault is the world’s guarantee of crop diversity

in the future; whether any survivors of our civilization would be able to reach it is a question we will hopefully never have to answer.

On the drive into town, it felt like we could slip into Lyra’s Svalbard at any time. The mountainsides above the town are covered by the remains of aerial ropeways that once took coal from mines to the harbor; the mine entrances themselves, which are little more than large holes in the side of the mountain; and a handful of forbidding abandoned factories, rumored to host raves. The grim wooden hostels were now bunk rooms for hikers, and the dingy bars they frequented looked as if they’d seen their fair share of fights. The super- markets warned customers not to bring their guns into the store. I had my picture taken—quickly—by the sign with a polar bear inside a big red triangle on the edge of town. Underneath were the words “Gjelder hele Svalbard,” meaning “applies to all of Svalbard.”

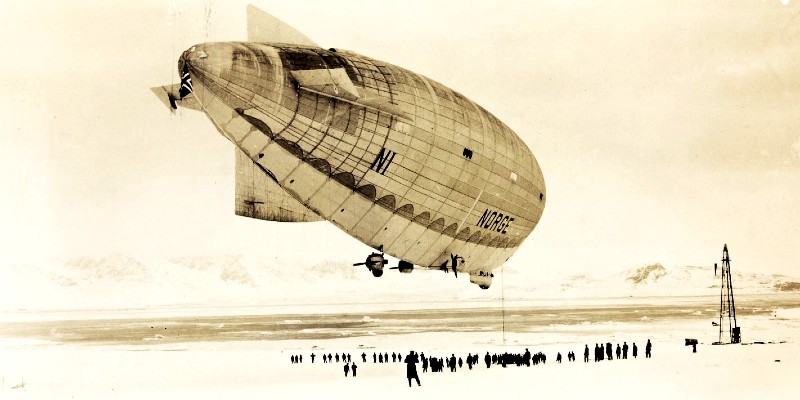

Down by the quayside, past where the scientists monitoring the melting permafrost park their half-tracks, is a small black wooden shack with a sizable wooden cutout of a polar bear looking straight at you. On the front are the words “North Pole Expedition Museum.” Right next to that label is a picture of a zeppelin. Airships had once flown over Svalbard.

Entering the shack is like stepping into a fantasy world. With its faded cuttings, black-and-white pictures, typed notes, and shaky newsreel footage, the museum tells the story of the aeronauts who once upon a time explored the unknown lands of the North Pole by hot-air balloon, airship, and primitive airplane. There is a section about Swedish hero Salomon August Andrée, who decided he would try to fly from Svalbard to the North Pole in a balloon. On July 11, 1897, he and his two crewmen took off for the pole, floated over the horizon, and disappeared. It would be another thirty-three years before their skeletons were found.

Another section of the museum is dedicated to the not- so-derring-do of journalist and all-around chancer Walter Wellman. He attempted three times—in 1906, 1907, and 1909—to fly to the North Pole in a sausage-like airship called the America. In 1909, the America managed to stay in the air for a couple of hours before it crashed. Despite this further setback, Wellman was determined to return the following year with a larger airship, but he never did. His dream of flying to the North Pole died when he heard of Dr. Frederick Cook’s claim to have reached the pole on foot. Instead, the following year he decided to fly across the Atlantic in the America, an endeavor that met with as much as success as his polar flights.

In truth, the exhibition is really about one man and one type of machine: Umberto Nobile and airships. Prodigy, dirigible engineer, aeronaut, Arctic explorer, member of the Fascist Party, opponent of Mussolini, maybe even Soviet spy, and always accompanied by his dog, Titina, Nobile twice flew jumbo-jet-size airships—lighter-than-air craft that he designed and built—on the epic journey from Rome to Svalbard to explore the Arctic. The N-4 Italia was the second of these flying machines.

In 1926, a dirigible he built and piloted, the Norge, became the first aircraft to cross the roof of the world from Norway to Alaska. It may even have been the first aircraft to reach the North Pole. His public falling-out with his famous co-leader, Roald Amundsen, over who should take credit for the flight made headlines across the United States—headlines that were perhaps matched only by the news that when Nobile was invited to Washington, Titina, who had flown over the North Pole with him, had relieved herself on the carpet of the White House itself.

In 1928, he ignored all the omens—and all his enemies—to return again to the North Pole in the Italia, but he never did become the first man to land at the pole from an airship. The crash of his vessel out there on the pack ice made front-page news around the world. The disappearance of many of his men was a mystery that has never been solved, with rumors of cannibalism never fully disproved. His treatment at the hands of Mussolini when he eventually returned to Rome was compared by his supporters to that of Alfred Dreyfus by the French government at the end of the nineteenth century.

This book, then, is the story of Nobile, his friends and enemies, their expeditions, and the airships and airplanes they flew, of the end of the golden age of polar exploration—that era when the pilot replaced the tough man of Arctic exploration in the public imagination and when the zeppelin and the airplane battled it out in the Arctic skies for the future of aviation, a time when some countries even considered banning aviation altogether because it was so dangerous. It is the story of some of the women, such as millionaire Louise Boyd, who up till now have been written out of the tale. It is a story that incorporates the rise of fascism and the struggle against it. It is also the story of a moment in time when many people thought there was a lost continent hidden at the North Pole behind the ice and fog.

Today, in Bedford, United Kingdom, in Paris, in California, and in Jingmen, China, a new generation of airship engineer, pilot, and dreamer is looking to explore the Arctic skies once more.

In Kings Bay, hundreds of miles to the north of Longyearbyen, a huge metal mooring mast was erected to secure Umberto Nobile’s airships. It stands there waiting, still, for the explorers and their airships to return again.

___________________________________