One day in the early 20th century, a man called Andrew Helgelien received a letter from a woman he had corresponded with for a while. The woman was a land-owning widow of means, based in Indiana, but of Norwegian descent like himself. Andrew had first written to her after seeing her personal ad in a newspaper for Scandinavian immigrants. The two of them had hit it off, and were already planning their future together. Enclosed with the letter was a dried four-leaf clover for luck. Little did Andrew know on that day that the woman he was so enamored with would later come to be known as one of the most prolific women serial killers in American history, and that he was to become the victim that eventually exposed her.

Over a hundred years later, on a beautiful, sunny September day, two friends and I made the steep trek up to a long-abandoned tenant’s farm in Selbu, Norway. There were no houses there anymore; just grassy knolls where they once had been, and the area surrounding the small farm had become thickly overgrown ever since its abandonment. The only thing that made the place out as something extraordinary was the homemade plaque that the local historical society had put up and surrounded with a low fence. The wooden plaque read: Størsetjare, Brynhild P. Størseth (Belle Gunness) homestead. This peaceful spot in the Norwegian woods had once been the childhood home of a serial killer.

My friends and I milled around in the clearing for a while, taking pictures and admiring the golden sunlight, then one of us – I can’t remember who – suddenly spotted four-leaf clovers growing around the base of the plaque. One of my friends climbed the fence to pick them, and it turned out to be three lucky clovers, one for each of us. We were immensely pleased with our find as we made our way back home. Only later did we remember Andrew Helgelien and his fate, and realized, with a smidge of dread, that four-leaf clovers from Belle Gunness were perhaps not a token of good fortune. We still kept them, though, and were still pleased. I wish I could say that I still have mine, but sadly – in an effort to preserve it – I pressed it in a book, and forgot which one. I have looked for it many times, but so far had no luck. Perhaps whatever magic it possessed climbed into my head and lodged there like a seed, later to be turned into In the Garden of Spite, my first novel about 19th century female serial killers.

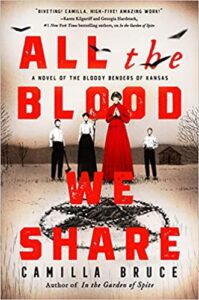

Women serial killers are generally very little talked about. Compared to their male counterparts they have a tendency to slip into obscurity almost as fast as they arrive. For decades, this caused the press to declare every one that emerged the first of her kind, even if she never was. To my knowledge, the first named woman serial killer in the US was Lavinia Fisher, who was executed in 1820. Like the Bender family in my new novel, All the Blood We Share, Lavinia and her husband operated an inn, the Six Mile Wayfarer House, where guests allegedly disappeared after drinking the hostess’ poisoned tea. How much of Lavinia’s story that is true is still up for debate, but what is almost certainly true, is that there were other women serial killers before Lavinia’s days, only they didn’t get caught.

After the arrival of the internet, our collective memory has become much better, but there is still a tendency to overlook women serial killers, even if one would think that their rarity would make them more – not less – worthy of attention. It is as if we are still clinging to the idea of women as inherently good and nurturing to such a degree that we collectively balk at them being capable of cold-heartedness and violence, despite ample evidence to the contrary. Men are supposed to be the predators, while women are destined to be prey, and it seems to be very hard for people to flip that narrative. Never in history has this been more pronounced than in the 19th century, where strong Victorian ideals dictated what a woman was. Maybe that is just why they fascinate me so much, the unruly members of what I think of as ‘the arsenic squad’ – named after the ladies’ of the era’s favorite method of killing.

I don’t think any of the female killers of the 19th century considered themselves feminists in the slightest. They did what they did for a variety of reasons, most frequently financial gain, but that doesn’t mean that their actions didn’t oppose, or shake up, the contemporary female ideal. The Victorian woman was supposed to be ‘the angel in the house’; mild tempered and always sunny. She was considered to have a childlike intellect and a delicate constitution. For this reason, many people didn’t think women even capable of violence, let alone murder. When women nevertheless killed, it became a problem for society that almost overshadowed the crime itself, causing many murder cases to end up in acquittal by default, or an insanity verdict – because how else could one explain that a delicate angel turned to murder? This is particularly noticeable in cases where the accused had some standing in society – like Lizzie Borden – but it trickled down to the lower classes as well. In the case of Belle Gunness, there were even rumors that she had secretly been a man all along, because it was just too unthinkable that a woman of means and a mother of three had killed and dismembered for years. It just wasn’t supposed to be in her nature.

The Victorian prejudices weren’t necessarily a bad thing for women killers, though. It is very easy to hide in plain sight if society deems you toothless. Belle Gunness, for instance, lamented in a letter to a suitor how she needed a man to take care of her farm so she could dedicate herself to the house and her children, as any good woman should. She also pretended to be too delicate to do the butchering in the barn herself. Kate Bender, who spearheads All the Blood We Share, went the other way and used her sexuality as a lure at a time where this was mightily frowned upon. Kate also took advantage of the spiritualism craze that raged in the 1870s to try to make a name for herself, realizing – perhaps – how this was one of the very few ways a woman could break free from the mold. And as puzzled as we may be today that women were considered to be so incapable of murder, it baffled the murderesses as well. The very prolific serial killer Jane Toppan, surprised by her own insanity verdict, commented in the Boston Post: “How can I be insane? When I killed the people, I knew I was doing wrong.”

As a writer, women serial killers of this era call to me just because of their double transgression: that against the victim, and that against the contemporary ideals. Just by doing the things they did, they challenged a rigid system and the perception of their gender, and I find that enormously fascinating. There is also the added of bonus of working with true crime that happened so long ago that no one who were directly affected are still alive. There are no more open wounds, and that, I think, makes it easier to explore the real events without running the risk of doing harm.

I didn’t think of any of these things on that beautiful September day when I visited Belle Gunness’ childhood home – all my books were still in the future, but perhaps there was some luck in that four-leaf clover after all, because working with this material has been an eye-opener, not just into another time, but into our own time as well. Though a lot has changed, some things have not: men are still predators, women still prey – and as long as that is the case, perhaps it isn’t entirely unhealthy with a little reminder that sometimes, it is the other way around.

***