I started writing crime novels back in the dark ages—the early eighties. I had always wanted to be a writer, but somehow other things had gotten in the way of my doing that—two years of teaching high school English, five years of being a school librarian on an Indian reservation, and ten years of selling life insurance, not to mention the births of my two children.

In 1982, at age 38 and as a divorced single mother, I finally gave myself permission to start living that dream. I hadn’t been allowed in the Creative Writing program at the University of Arizona in 1964 on account of my being a girl. As a consequence, my first effort at fiction writing turned out to be a 1,400 page opus, a thinly fictionalized version of my first husband’s and my encounter with a serial killer in Tucson, Arizona, in 1970. Had I been allowed in the class, I might have learned that I needed to leave some things out. Since I wasn’t, I put everything in—hence the 1,400 pages.

Not surprisingly, that effort was never published, even after my agent suggested I cut it in half. The editors who turned the manuscript down said that the parts that were fiction were fine and the parts that were non-fiction were unbelievable and would never happen, even though they already had. And although that manuscript, By Reason of Insanity, never saw the light of day, it was important on-the-job-training. In the course of writing 1,400 pages, the equivalent of three complete novels, I taught myself how to do pacing, plotting, character development, scene setting, and dialogue.

Finally, when that original agent (who is still my agent to this day) suggested I try writing something that was entirely fiction, I did so, or at least I tried. For six whole months I worked on a murder mystery set in Seattle, and it just wouldn’t get past go. Finally, in the spring of 1983, I sent my two school-age kids to Camp Orkila for spring break, while I went to Portland by train to spend five days with a friend from my days in the life insurance business.

I boarded the train with a stack of blue lined notebooks and a fistful of pens. As the train pulled out of Seattle’s King Street Station, I asked myself, “What would happen if I wrote this book through the detective’s point of view?” So I took pen to paper and wrote, “She might have been a cute kid once. That was hard to tell now, she was dead.” And from the moment I wrote those two sentences, I was at the crime scene with homicide cop J.P. Beaumont, walking in his shoes, seeing things through his eyes, hearing what he heard and said, yes, but also what was going on in his head.

J.P. Beaumont and I have been author and character from that day to this. I’m currently at work on Beaumont # 25, Nothing to Lose, due out in 2022. After writing a total of nine Beau books, I learned something important about myself—I have a limited attention span, and by then I was tired of him. When I threatened to knock him off in the next book, my editor suggested I write something else, and so I wrote the first Walker Family Book, Hour of the Hunter.

The Beau books are always written in the first person in a straight, uncomplicated timeline. Hour of the Hunter was written through seven or eight different points of view with an elastic timeline that moved back and forth over seventy years. Writing that was like going on vacation, and when I went back to writing about J.P., he was fun again. So my editor suggested I come up with another character. Enter Joanna Brady.

Writing in the first person requires a particular kind of focus and discipline. The reader only knows what the main character sees, hears, says, or thinks. So for Joanna I decided to use a third person narrative. Beau started out as a middle-aged male homicide cop. I had never been any of those things, so I had to do a lot of research to make that work. For the new series, I decided on a female protagonist who had never been in law enforcement. When I first met Beau, he was a Seattle native, so I had to do a lot of research in that regard as well. With Joanna, I decided to press the easy button and set her stories in southeastern Arizona where I grew up.

Eventually, after years of alternating Beaumont, Joanna, and the Walkers, I hit my attention span limit once more. That’s when Ali Reynolds appeared on the scene. She’s a former television news anchor who has to reinvent herself when both her career and her marriage derail simultaneously. I know a little about reinventing myself. That’s what I did when, in the aftermath of my divorce, I came to Seattle and essentially started over.

One of the advantages of writing in series form is that I’ve been able to watch my characters grow and change over a long period of time. In the first book, Joanna finds herself a widow with a single child to raise. Eighteen books later, she’s remarried, has two additional children, and has just been reelected sheriff for the third time. In seventeen books, all of them written in the third person, Ali Reynold has found her right place, her hometown of Sedona, Arizona, and her right man, a guy named B. Simpson. Together the two of them run a cyber security company called High Noon Enterprises. In the twenty-five Beau books, all of them written in first person, Beau has left Seattle PD and spent years working for the attorney general’s Special Homicide Investigation Team (SHIT). Now retired, he works for a volunteer cold case organization called TLC, The Last Chance.

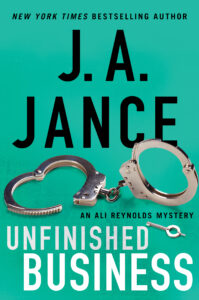

Shortly after I started writing the new Ali Reynolds book, Unfinished Business, I realized it concerned a cold case with tendrils in both Arizona and Washington State. It just so happened that I had a perfectly good cold case investigator named J.P. Beaumont working in the Seattle area. There was only one problem—the Beau books are published by William Morrow at HarperCollins while the Ali books belong to Gallery Books at Simon and Schuster. It took some time to negotiate a peace treaty between the two houses, but eventually I prevailed and received permission for Beau to have a role in the new Ali book.

Since the Ali books are written in third-person, I blithely assumed Beau would show up the same way. Boy was I wrong about that! When he appeared, he utterly refused to do anything in the third person. After telling me in so many words, “My way or the highway,” I gave up—and Beau’s scenes are written in his usual seventy-something, curmudgeonly tone of voice. When I sent the manuscript to my most recent editor at Gallery, someone who had never read a J.P. Beaumont book, she encountered that scene, came to a full stop, and immediately went through the manuscript, changing his portions from first person to third.

I thought maybe if someone else did the changeover, it would work form me, but it didn’t. As soon as I read it, I was dismayed to find that the character who had walked and talked and lived for close to forty years had suddenly morphed into a cardboard cutout. So I wrote back to the editor and told her, just as Beau had told me, “My way or the highway. First person or nothing.” The editor definitely did NOT want nothing, and so scenes involving Beau returned to first person.

For Ali-only readers and for brand new ones, they may hit that first Beaumont section and feel a bit lost for a moment, but trust me, they’ll catch on eventually. And for readers who have been Beau people from day one? I think they’ll be happily surprised to find their beloved character lurking between the pages of an Ali book.

As for me? In the fall of each school year, regardless of grade level, students in my day were required to write an essay about what they did on their summer vacation. What did writing Unfinished Business do for me? It taught me once and for all that characters are not to be trusted. Sometimes, regardless of what authors think, characters have minds of their own.

***