Amelia Earhart climbed into her plane on July 2, 1937 en route to Howland Island in the central Pacific Ocean. She was never seen or heard from again. There are theories. She was a castaway on Gardner Island in the Republic of Kiribati. She was a prisoner in the Marshall Islands. Even with all of our computing capability and satellites 83 years later, we have no idea where she is.

Agatha Christie kissed her daughter Rosalind good night, climbed into her Morris Cowley, and for eleven days, could not be found.. See, her husband cheated on her again, this last time with Theresa Neal. The famous novelist, traumatized so much that she developed psychogenic amnesia, adopted a new personality as Neele and straight-chilled at a spa in Harrogate. She was alive and well—at least not suffering from injuries that could be seen with the naked eye

Regular people disappear all the time. The FBI’s National Crime Information Center’s Missing Person and Unidentified Person Files for 2019 notes that there were nearly 88,000 active missing person records and 609,275 missing person records entered into NCIC, with nearly 300,000 of those being female. In California, 42,454 adults went missing (13,253 adult women) in 2019. From this number, 23 abducted, 471 missing under suspicious circumstance, 2,901 under unknown circumstances, and 36,706 voluntarily missing.

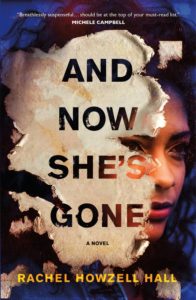

In my new mystery, And Now She’s Gone, new private investigator Grayson Sykes is in the business to find missing things—from girlfriends to beloved Chihuahuas. In her first big case, she’s hired by physician Ian O’Donnell to find his missing girlfriend, Isabel Lincoln. Ian isn’t saying, but something’s happened in their relationship to cause Isabel to flee one last time—and this time, she’s taken the doctor’s beloved Labradoodle Kenny G with her. But Grayson senses that Isabel hasn’t gone far, and it is up to her to twist through this city of 4 million people to find one woman who doesn’t want to be found.

Our smart phones track our locations with satellites, and other than using carrier pigeon, there’s nothing you can do about that. We tag ourselves in social media posts—look at me in the Bahamas, look at this liquid nitrogen-laced smoky cocktail at this restaurant in Beverly Hills, hey, I’m at a cool conference in Taos. We log nearly every interaction on Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat and Instagram. Sometimes, we even receive discounts on tapas or tires because we ‘checked in’ on Yelp. We tell people all the time: I AM HERE. According to Pew Research Center, over 70 percent of Americans use social media, with Facebook being the most popular at 69 percent.

How can you possibly disappear when social media companies, cellphone carriers, hell, The Olive Garden, is tracking your movements, your likes, your spending habits?

Is it hard to vanish?

Los Angeles County is 4,753 square miles with nearly 22,000 miles of maintained roads. There are 10.04 million people and over 15 million registered cars. We have liquor stores and drug stores everywhere. Along with your purchase of Funyans and hand sanitizer, you can purchase pre-paid phone minutes and burner phones. Most importantly, Los Angeles has a Greyhound bus station. You don’t need a credit card or a RealID to buy a bus ticket. Just hop on and be gone. Who’d notice?

It’s not illegal to disappear. If you’re a mentally-sound individual not looking to cheat the insurance companies or running from the law, you can just… go. Is it a nice thing to do, leaving your family and friends behind? Is it ethical? Moral? Perhaps not. But you’re not breaking the law. You have the right to privacy.

Before I wrote And Now She’s Gone, I’d heard author Elizabeth Greenwood on a podcast talk about faking death as she promoted her book Playing Dead: A Journey Through the World of Death Fraud. I was fascinated as she talked about ‘dying’ in the Philippines in 2013. All she needed was a few hundred dollars to purchase a fake death certificate and then money to live her new life without a physical and digital trail.

I’m not the only one fascinated with intentionally vanishing.

There was a short-lived reality TV/game show called Hunted. Contestants had to evade detection for 28 days by trained experts in the FBI, CIA and military intelligence. The prize: $250,000.

Writer Evan Ratliff wrote about his attempts to disappear for a Wired magazine (who then turned Ratliff’s adventure into a contest that went viral). Ratliff left San Francisco with business cards under a fake name, two prepaid cell phones, and a cashier’s check worth $477. For those who found Ratliff, Wired paid a bounty of $5,000. Despite his preparation and deliberation, he was found on Day 16 in New Orleans.

In an upcoming article for Writer’s Digest by David Corbett, I talked about those cameras fixed atop some traffic signals around Los Angeles. Called ALPRs, or automatic license-plate readers, these cameras take pictures of vehicles and their license plates, and the system then stores and tracks your car’s make, model, and color. Civil liberties groups like Electronic Frontier Foundation are challenging the legality of technology like this—they contend, among many things, that these tracking systems are a violation of privacy. And for someone who wants to vanish, these cameras at major intersections make it even harder.

What about you? Would you be willing to leave everything behind—your dog, your kids, your life—to start over as someone else? What’s keeping you here?

***