When I write, I don’t think in terms of redemption. That feels too calculated. It also feels too biblical and, well, my feet are firmly planted in the evolution camp. I’m right there with the quasi-amphibian tetrapods 350 million years ago, trying to figure out how to consume oxygen and make it work for all the creatures to come.

Life is too messy for a clean redemption arc. And don’t we want more from our novels than reassurance that healing is possible or that the sins can be washed away? That through some act we are transformed? Again, sins. That whole Old Testament/New Testament thing again. I’m not sure it’s that easy. Instead, don’t we want to challenge both our characters and our audiences to grapple with the density of reality so that both characters and readers come to see the world as it truly is and, in turn, decide how to handle that knowledge? What’s wrong with not knowing?

I mean, sheesh, if even half the novels out there featured a redemption arc we would all be bored out of our brains and, by the way, if all these sins are getting cleaned-up why is there still so much misery in the world? And on its face, can we now dispense with the notion that these religious parables, as some sort of instructive toolkit, have done any good over the last couple of millenniums?

If you’re someone who appreciates having a superstructure to explain it all, I won’t judge. But do we really need to have it exuding from all our fictional works too? Estimates suggest that somewhere in the neighborhood of 107 to 117 billion human beings have lived or are alive today, and I don’t mean to oversimplify it, but doesn’t the overwhelming evidence suggest that—despite the influence of churches and religions worldwide—that there’s still a whole lot of misery in our midst?

Basically, everywhere you look?

When I first started writing, I attended a workshop where the presenter encouraged us newbies to develop a “character bible” for our protagonist, antagonist, and main side characters. (Okay, maybe I do have an aversion to the word bible because this process scared the hell out of me.) She had a thick booklet like an extended Mad-Libs exercise and we were supposed to fill in the blanks of our characters’ lives. Among the suggestions was to write down each character’s favorite color in, say, fourth grade. And then note how that color might have changed over time.

Casting no aspersions on other writers who might find this kind of process useful, I almost ran from the room. This kind of data seemed useless, arbitrary. And irrelevant.

How would knowing that “purple” in fourth grade became “orange” in high school tell us anything about the darkness of life that creates true monsters?

I think we read for deeper reasons than that. I consider myself a fairly upbeat guy, but I think one of the reasons we read is to watch others struggle.

Because life is hard. Because life is full of challenges. And because, as David Shields (Reality Hunger, How Literature Saved My Life) wrote, “A book should either allow us to escape existence or teach us how to endure it.”

For me, a good crime novel is riveting and immersive. But combine a good plot with fundamental questions about the meaning of life and you’ve got my full attention. Not flipping the pages faster and faster but slowing down to sip the rich liquor and language of the character’s worldview. And combine those ingredients with a thinking, three-dimensional human being full of jagged edges and self-doubt, it’s like hitting the trifecta.

To wit:

The Lew Griffin Series by James Sallis

Not really crime fiction (at all) because the plot occasionally evaporates faster than a drop of hot water on the surface of the sun, but all six of James Sallis’ remarkable series lean into questions of identity, imagination, existence. Griffin channels Camus, Sartre, Pynchon and host of other visual and musical artists. All six novels are compelling in their own way, but savor Black Hornet in particular, when our slacker black PI Griffin takes in the militant observations of Chester Himes.

The Night Always Comes by Willy Vlautin

The exquisite works of Willy Vlautin feature struggling characters who live on the edge, but for the first time he applies himself to crime fiction in The Night Always Comes. Our main character, Lynette, works multiple jobs, manages a developmentally disabled older brother, and lives in a house with a roof that leaks when it rains. Lynette’s dreams of a better home and taking a step up on the economic ladder run smack into dark choices and a harrowing odyssey. We watch as Lynette develops the ability to be honest with who she is and the choices she made along the way. The writing is spare, talcum dry. If you can’t feel Lynette’s messy world and the bumps on her head as she tries to bash her way to a better world, you live in a glass dome.

Blood on the Tracks by Barbara Nickless

Blood on the Tracks starts out as a thriller, morphs into a mystery, and turns back again into a movie-ready action-packed finish. But “movie” sounds like this story follows the normal arcs. It doesn’t – because it’s a film. It’s no redemption story. It’s more complicated than that. It’s untidy and chaotic–in a good way. It’s ambitious and sprawling. The story swoops from big picture (hey, stop that train!) to intimate. It’s both violent and raw. Blood on the Tracks is about the ghosts of war, racism, class, rank, a harrowing search for identity and, of course, truth and justice. It rolls all those topics, and more, into a multi-faceted manhunt, at first, and clue-finding mystery. Railroad Police Special Agent Sydney Rose Parnell is a complex and interesting character. She’s haunted for many reasons, including the fact that she worked in corpse retrieval during the war in Iraq and she was also involved in a situation covering up certain atrocities over there. Sydney Rose is so relatable because her demons feel real. (This was Nickless’ debut, the first of many outstanding books.)

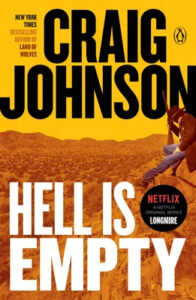

Hell is Empty by Craig Johnson

Hell is Empty is an existential journey that touches on good and evil, life and death, dedications and obligations, mountain peaks of insight, and the depths of misery. The journey is about confronting your monsters, taking on your enemies. It’s more character study than tale of suspense but the slow-motion pursuit up this snowy, rugged peak certainly has its hair-raising moments for Sheriff Walt Longmire—and for us. As Longmire chases an escaped prisoner up and up, it’s Longmire’s conversations with Virgil White Buffalo that make Hell is Empty sing. The climb continues, the peak draws closer, the end is nigh. Along the way, Longmire consults a battered paperback copy of Dante’s Inferno. Climbing higher as he probes the further depths of hell might be pushing the obvious button but not in Johnson’s capable, understated style. The cold closes in, the light plays tricks. “There were shadows ahead, indistinct and nebulous, writhing with the flying snow. I tried to concentrate on the shapes, but as soon as I looked, they would swirl away and dissolve in the dark air.” Sure, Longmire gets his guy but that’s the way I like my stories—open-ended and full of uncertainty.

****