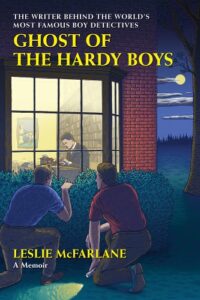

Excerpted from Ghost of the Hardy Boys: The Writer Behind the World’s Most Famous Boy Detectives, by Leslie McFarlane

___________________________________

This example of calmness in the face of disaster didn’t really help. It was all very well for Dave Fearless to meet catastrophe with aplomb. He could count on Bob Vilett and Captain Broadbeam to haul him to the surface, while Pat Stoodles lent encouragement by bellowing “Heave-ho, bejabers!” I couldn’t count on anyone—except, perhaps, Edward Stratemeyer.

It turned out that I could count on Edward Stratemeyer. Before the week was out a long envelope brought another outline, accompanied by a letter explaining his “other plans.” He had observed, Stratemeyer wrote, that detective stories had become very popular in the world of adult fiction. He instanced the works of S.S. Van Dine, which were selling in prodigious numbers as I was well aware. S.S. Van Dine was neither an ocean liner nor a living man but the pseudonym of Willard Hungtington Wright, a literary craftsman who wrote sophisticated stories for Mencken’s Smart Set.

It had recently occurred to him, Stratemeyer continued, that the growing boys of America might welcome similar fare. Of course, he had already given them Nat Ridley, but Nat really didn’t solve mysteries; he merely blundered into them and, after a given quota of hairbreadth escapes, blundered out again. What Stratemeyer had in mind was a series of detective stories on the juvenile level, involving two brothers of high school age who would solve such mysteries as came their way. To lend credibility to their talents, they would be the sons of a professional private investigator, so big in his field that he had become a sleuth of international fame. His name—Fenton Hardy. His sons, Frank and Joe, would therefore be known as…

The Hardy Boys!

This would be the title of the series. My pseudonym would be Franklin W. Dixon. (I never did learn what the “W” represented. Certainly not Wealthy.)

Stratemeyer noted that the books would be clothbound and therefore priced a little higher than paperbacks. This in turn would justify a little higher payment for the manuscript—$125 to be exact. He had attached an information sheet for guidance and the plot outline of the initial volume, which would be called The Tower Treasure. In closing, he promised that if the manuscript came up to expectations—which were high—I would be asked to do the next two volumes of the series.

The background information was terse. The setting would be a small city called Bayport on Barmet Bay “somewhere on the Atlantic Coast.” The boys would attend Bayport High. Their mother’s name would be Laura. They would have three chums: Chet, a chubby farm boy, humorist of the group; Biff Hooper, an athletic two-fisted type who could be relied on to balance the scales in the event of a fight; and Tony Prito, who would presumably tag along to represent all ethnic minorities.

Two girls would also make occasional appearances. One of them, Iola Morton, sister of Chet, would be favorably regarded by Joe. The other, Callie Shaw, would be tolerated by Frank. It was intimated that relations between the Hardy boys and their girl friends would not go beyond the borders of wholesome friendship and discreet mutual esteem.

I got the message. There was to be no petting, as it was known at the time. None of the knee-pawing, tit-squeezing stuff that was sneaking in to so much popular fiction, to the disgust of all right-thinking people. Wholesome American boys never got a hard-on. (Why was that?)

I skimmed through the outline. It was about a robbery in a towered mansion belonging to Hurd Applegate, an eccentric stamp collector. The Hardy Boys solved it.

What a change from Dave Fearless! No man-eating sharks. No octopi. No cannibals, polar bears or man-eating trees. Just the everyday doings of everyday lads in everyday surroundings. They didn’t go wandering all over the seven seas, pursued by imbecile relatives. They stayed at home, checked in for dinner every night like other kids. They even went to school. Granted, they didn’t appear to spend very much time at school; most of the outline seemed to be devoted to extracurricular activities after four and on weekends. But they went.

I was so relieved to be free of Dave Fearless and his dreary helpers that I greeted Frank and Joe Hardy with positive rapture, and I wrote to Stratemeyer to accept the assignment. Then I rolled a sheet of paper into the typewriter and prepared to go to work.

Then I paused and gave the project a little thought. The sensible course would have been to hammer out the thing at breakneck speed, regardless of style, spelling or grammar, and let the Stratemeyer editors tidy it up. Bang it out, stuff the typed sheets in an envelope and put it in the mail, the quicker the better, and get going on the next book. In this sort of business, at the payment involved, time was money, output was everything.

Writers, however, aren’t always sensible. Many of them enjoy writing so much that they would go on doing it even if deprived of bylines and checks, which is why agents are born. The enjoyment implies doing the best one can with the task in hand, even if it is merely an explanatory letter to the landlord. (There is no special virtue in this. Writers just can’t help it.)

It seemed to me that the Hardy boys deserved something better than the slapdash treatment Dave Fearless had been getting. It was still hack work, no doubt, but did the new series have to be all that hack? There was, after all, the chance to contribute a little style, occasional words of more than two syllables, maybe a little sensory stimuli.

Take food, for example. From my boyhood reading I recalled enjoying any scenes that involved eating. Boys are always hungry. Whether the outline called for it or not, I decided that the Hardy boys and their chums would eat frequently. When Laura Hardy packed a picnic lunch the provender would be described in detail, not only when she stowed it away but when the boys did. And when the boys solved the mystery of the theft, Hurd Applegate wouldn’t stop at a mere cash reward. He would come up with a lavish dinner, good for at least two pages of lip smacking. Maybe even belches.

And then there was humor. There hadn’t been so much as a snicker in the whole Dave Fearless series. This stood to reason: a man-eating shark is no laughing matter. Next to food, however, boys like jokes. Why not inject a few rib ticklers into The Tower Treasure? Chet Morton was described as a “fun loving lad,” and, as he was supposed to be “chubby,” it followed that food interest might be maintained by making him a glutton. The cast of characters also gave passing mention to Chief Collig, head of the Bayport Police Department, and his associate, Detective Smuff. While the outline did not suggest that these lawmen were comical fellows, it did seem that anyone named Collig had to be a pretty stodgy cop and that Smuff would simply have to be a dunderhead.

I could hardly wait to get at them.

But why go to all this trouble? If The Tower Treasure was a little better written than the usual fifty-cent juvenile, who would get the credit? The nonexistent Franklin W. Dixon. If better writing and a little humor helped make the series a success, who would benefit financially? The Stratemeyer Syndicate and the publishers. The writer who brought the skeleton outline to life wouldn’t get a penny even if the books sold a million—which, of course, seemed impossible at the time.

So what? I decided against the course of common sense. I opted for Quality.

___________________________________

Excerpted from Ghost of the Hardy Boys: The Writer Behind the World’s Most Famous Boy Detectives, by Leslie McFarlane. Published by David R. Godine Publisher. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.