LIZZIE BORDEN’S SECRET screamed a front-page headline in the Boston Daily Globe’s morning edition for Monday, October 10, 1892. The fourteen-column article that followed rolled out shocking new evidence about the axe murders of Borden’s parents in Fall River, Massachusetts, a crime that transfixed America that year. The secret? Borden, who was awaiting trial for the brutal killings, was pregnant. Her outraged father, Andrew, had been overheard threatening to banish her from their home unless she revealed “the name of the man who got you into trouble.” She refused. A day later both he and Lizzie’s stepmother, Abby, were dead.

More damning revelations followed. The morning of the murders, several passersby had seen Lizzie at the upstairs window where Abby’s mutilated body was found. A rubber cap or hood covered her head, and while the significance of this strange headwear was not mentioned in the article, armchair detectives could deduce it was worn to protect her hair from blood spatter. Other witnesses claimed to have heard Lizzie offering to buy the silence of the family’s maid, the only other person known to have been in the house about the time of the murders. “Keep your tongue still,” she allegedly whispered, “and you can have all the money you want.”

The Boston Daily Globe splashed its Borden “scoop” on the front page of its October 10, 1892 editions.

The Boston Daily Globe splashed its Borden “scoop” on the front page of its October 10, 1892 editions.

The article presented the statements of twenty-five witnesses, filling almost two full pages of a ten-page paper with incriminating evidence: Lizzie’s inquiries about her father’s will. Her animosity toward her stepmother. Her suspicious behavior and strange comments in the hours after the bodies were discovered. The Globe’s star crime reporter, twenty-four-year-old Henry G. Trickey, claimed to have spent six weeks compiling “every fact of importance” in the hands of police and prosecutors. Lizzie Borden would not stand trial until the following June, but the judicial process now appeared to be a formality. She had been convicted in the court of public opinion.

There was, however, a problem with the blockbuster story.

Hardly a word of it was true.

Welcome to a bizarre tale of fake news in the Gilded Age.

***

The Globe’s Lizzie Borden “scoop” is a dark and little-known episode in the history of American journalism, a rock-bottom point for a profession that was struggling for credibility and respectability. The Fall River Tragedy, one of the earliest books to chronicle the Borden case, ranked it as nothing less than “the most gigantic ‘fake’ ever laid before the reading public.”

Newspaper hoaxes were shockingly common in the nineteenth century as publishers vied to out-do rivals and boost circulation with exclusive stories—some accurate, some not. “Faking,” Texas A&M University communications professor Randall Sumpter has noted, “was a rampant journalistic practice.” Mark Twain, Edgar Allan Poe, and Benjamin Franklin all passed off fiction as fact at some point in their careers. The New York Sun’s legendary moon hoax of 1835 offered vivid descriptions of creatures living on the lunar surface, while New York’s Herald once concocted a realistic and alarming report of rampaging beasts in Central Park, in a misguided attempt to warn of safety risks at the park’s zoo. Sumpter, in a book on early journalism training, tells of a Buffalo newsman who acquired fingers from a cadaver, then wrote stories claiming he had discovered them and demanding the police investigate a possible murder.

The Globe’s correction and apology, published the following day.

The Globe’s correction and apology, published the following day.

The Borden story, however, was not a hoax—at least, not a deliberate one perpetrated by the journalist who wrote it. Trickey and his editors were convinced their information was true. They rolled out the allegations in compelling and credible detail, complete with the names, addresses, and occupations of the purported new witnesses. And Trickey, despite his slippery-sounding surname, was the most accomplished and trusted reporter in the newsroom. He had been a journalist since he was sixteen, and his assignments ranged from the crime beat to political affairs, including stints covering major stories in Canada. By the time he tackled the Borden case he had covered more than sixty homicides for the Globe, earning the unofficial title of the paper’s “murder man.” He was impulsive, fiercely competitive, tireless in the pursuit of stories, and above all staunchly loyal to The Globe. “His loyalty was almost a failing,” his employers acknowledged in hindsight. “It sometimes outran his caution.”

___________________________________

This story originally ran in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine (Oct. 2019)

___________________________________

The Globe’s evening edition for October 10 reveled in its success, boasting the story had astounded “all New England” and created mob scenes at newsstands. “Doubts of Lizzie A. Borden’s guilt,” the paper proclaimed, “were shaken.” It had been widely believed that Lizzie must be innocent; the attacker was a tramp or fiend who had somehow managed to enter and leave the house undetected. No young woman from a good family, no daughter of a successful businessman, many people reasoned, was capable of such brutal acts. She was thirty-two years old and respectable, a churchgoer who supported an array of local charities. Suddenly, her scandalous double life had been exposed, along with several possible motives for murder—protecting a secret lover, the shame of a pregnancy out of wedlock, a threatened banishment from the household.

- An artist’s sketch of Lizzie Borden at the inquest into her parents’ murders. (Source: Boston Daily Globe)

- A depiction of Lizzie Borden’s arrest. (Source: Boston Daily Globe)

A case that had horrified the public was now a salacious one as well. The Globe’s scoop “seemed at last to bring into the case the ‘love interest,’” noted Edmund Pearson, a pioneering true crime writer who studied the case in the 1920s, “for which many newspaper reporters had almost pined away and died.” Trickey and his editors, in their zeal to break the story, never bothered to check whether the most sensational allegation—that Lizzie was pregnant—was true.

***

The story unravelled with lightning speed. Borden’s lawyer, Andrew Jennings, denounced the allegations as false and “trumped-up.” Rival Boston papers fought back with stories headlined “A Fake” and “A Tissue of Lies.” Within twenty-four hours, the Globe acknowledged its blockbuster had been “proven wrong in some particulars”—most importantly, about Lizzie’s “physical condition” at the time of the murder. She was not pregnant, the Borden family’s doctor confirmed, and never had been. By the time the late-afternoon edition rolled off the press on October 11, the paper was in full retreat. Much of the information in its original report “is false,” it now acknowledged, “and never should have been published.” A front-page apology was issued to readers and to Lizzie, “for the inhuman reflection upon her honor as a woman.”

The Globe refused to take responsibility for the debacle, proclaiming itself “an honest newspaper” and as much a victim of the false allegations as Lizzie. Its journalists had been “grievously misled” by a “remarkably ingenious and cunningly contrived story.” In a long statement published under his byline, Trickey described how he had purchased the information for $500—about $12,000 today—from Edwin D. McHenry, a private detective who had assisted the police during the murder investigation. Fearing the detective would sell the information to a competitor, Globe editors made no attempt to verify the allegations before rushing the story into print.

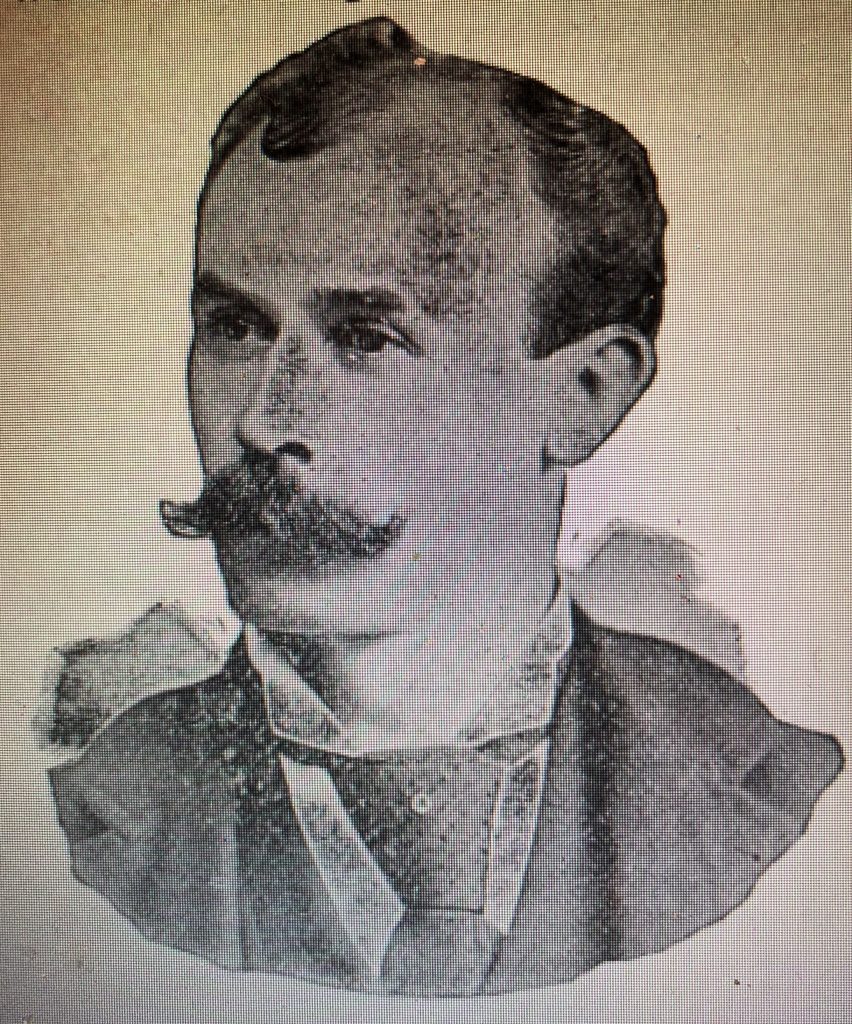

Henry G. Trickey (Source: The Fall River Tragedy)

Henry G. Trickey (Source: The Fall River Tragedy)

McHenry was still owed money for his legwork on the case and he may have seen the Globe’s cash-for-information offer as suitable compensation. He would later claim he planted the bogus story with the blessing of the Fall River police, who suspected Trickey was feeding information to Borden’s defense lawyers. The leak, according to the detective, was an elaborate ruse to catch the reporter passing along tantalizing details of the prosecution’s case. McHenry had demanded twenty-four-hours’ notice if the Globe planned to publish the information—enough time to reveal the hoax and prevent the accusations from appearing in print—but Trickey had reneged on the promise.

Edwin D. McHenry (Source: The Fall River Tragedy)

Edwin D. McHenry (Source: The Fall River Tragedy)

McHenry’s ultimate goal, however, may have been revenge. He and Trickey had clashed while investigating a high-profile murder in Colorado the previous year, and since then, McHenry later admitted, “we had not been on friendly terms.” But when they met again in the wake of the Borden murders, Trickey had begged him for information. “I want something big to scoop this gang of newspaper fellows who are in the town,” he told McHenry. Since Trickey seemed convinced that Lizzie had a secret lover, McHenry invented one. The “unscrupulous” detective, author and lawyer Cara Robertson has noted in a new book on the Borden case, “apparently relished the opportunity of doing Trickey a bad turn.” The elaborate hoax was payback.

Rather than sullying Lizzie’s reputation or prejudicing her defense, the Globe’s story and its quick retraction rebounded in her favor. For her supporters—and there were many, in Fall River and beyond—it was further proof an innocent woman was being persecuted. The avalanche of false evidence muddied the waters, making it difficult to know who or what to believe. “The final result of this wretched affair may well have been to add to the number of those who distrust the newspapers,” noted Edmund Pearson, “and to persuade them that if this damaging story were false, everything which seemed to tell against the prisoner might equally be false.” Cara Robertson is convinced the hoax and its fallout made Lizzie “a figure of sympathy” in the lead-up to her trial. With no eyewitnesses or physical evidence to link her to the killings, a jury deliberated for a little more than an hour before declaring her not guilty.

***

The “Lizzie Borden’s Secret” story, the scoop that never was, ended the career of a man hailed in the press as “one of the best writers upon criminal cases in the world.” A grand jury indicted Trickey on December 2, 1892 on a charge of witness-tampering. The authorities, still clinging to the bizarre notion he was in cahoots with the defense—despite his zeal in publishing a fabricated story that condemned Lizzie—now claimed he had tried to induce a key prosecution witness to leave the country. Trickey fled to Canada to escape arrest, traveling under the name Melzar—his wife’s maiden name—and posing as a salesman. A day after the indictment was announced, as he rushed to catch a train pulling out of a station in the Ontario city of Hamilton, he lost his grip on a handrail and slipped under the wheels. He died almost instantly.

In Fall River, the news was met with disbelief. “Many persons,” noted one Massachusetts newspaper, “were heard to express themselves as believing the story to be a fake.” Even the state’s attorney general was sceptical. Albert E. Pillsbury, who knew the reporter “pretty well,” ordered that inquiries be made to confirm that he was indeed dead. Trickey, he confided to a friend, was a man “capable of a number of things.”

Sources:

Boston Daily Globe, October 10-12, December 3, 5, 7, 1892

Buffalo Evening News, December 5, 1892

Fitchburg Sentinel, December 6, 1892

Gorbach, Julien. “Not Your Grandpa’s Hoax: A Comparative History of Fake News,” American Journalism: A Journal of Media History, vol. 35 no. 2 (2018)

Oakland Tribune, December 5, 1892

Pearson, Edmund. Studies in Murder (New York: Random House, 1938)

Porter, Edwin H. The Fall River Tragedy: A History of the Borden Murders. (Fall River, MA: Press of J.D. Munroe, 1893) Available online.

Robertson, Cara. The Trial of Lizzie Borden: A True Story (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2019)

Sumpter, Randall S. Before Journalism Schools: How Gilded Age Reporters Learned the Rules (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018)

___________________________________

Dean Jobb’s next book (coming in 2021 from Algonquin Books and HarperCollins Canada) recreates the crimes of Victorian-era serial killer Dr. Thomas Neill Cream, who preyed on women in the U.S., England and Canada. He teaches nonfiction writing at the University of King’s College in Halifax. Follow him on Twitter: @DeanJobb