—This story is a co-publication with The Delacorte Review.

It is the coldest of cold cases, a case so old the detective in charge of the investigation wasn’t born at the time of the homicide. The victim was initially known as Jane Doe number one, the first female homicide victim of 1947. Her anonymity was soon transformed into notoriety and her case evolved into the nation’s most infamous unsolved murder. London has Jack the Ripper. New England has the Boston Strangler. Los Angeles’ iconic homicide is not known by the moniker of the perpetrator, but the victim—The Black Dahlia.

The murder of Elizabeth Short has spawned numerous books, countless newspaper articles, several movies, in addition to video games and podcasts. The horrific homicide has sparked such enduring fascination that the crime has been transformed into kitsch. There is Black Dahlia lingerie, Black Dahlia perfume, Black Dahlia T-shirts, and a number of other schlocky items. At the Biltmore Hotel, where Short was last seen, the bar serves a Black Dahlia cocktail. A Michigan death metal band is called The Black Dahlia Murder. Unlike other crimes, there is no statute of limitations on murder and a homicide investigation is never closed until it is solved. While most decades-old murders slip into obscurity, the Black Dahlia case attracts so much attention that the LAPD has continued to assign the homicide to a specific detective since the lead investigator retired in 1960.

“After all these years, I still get about one call a week,” says LAPD Detective Mitzi Roberts, who has been in charge of the case for a decade. “Some are from people who’ve done a ton of research and have a theory. I get a lot of calls from people with repressed memories, who tell me the killer was their dad, or their uncle, or their neighbor, and on and on. Then there are the real nut jobs who claim to have solved the case based on astrological number or pyramids.”

She is pestered so often that her captain has advised her not to do any more interviews because they take too much time away from her current investigations. The question of why this case has fascinated so many for so long has intrigued Larry Harnisch and sent him on such an intensive and serpentine journey of research, interviews, and archival study that some consider him Los Angeles’ most knowledgeable Black Dahlia authority. When asked why there is still an obsessive focus on the case among crime buffs, he says, “I’ll defer to the theory of the original detectives, who came up with three reasons. One, it’s unsolved; two, the nickname; and three, the horrible nature of the crime. Take away any one element and nobody would care today. And I’ll add one more element: noir. This was post-World War II Los Angeles and the whole noir thing is very big now. That’s kind of given the case new life.”

The nickname alone, he says, was not enough. In Los Angeles, there had been the White Orchid murder, the Red Hibiscus murder, the White Carnation murder, and the White Flame murder, but none remained the cynosure of attention. There have been countless bizarre unsolved murders in Los Angeles and most of them have been forgotten. While other Los Angeles murder victims had been brutalized and their bodies mutilated, Harnisch acknowledges there was something sui generis about what the killer had done to Elizabeth Short. Her body was found in a weed-webbed lot in South Los Angeles, surgically severed in two, washed and scrubbed, posed, and completely drained of blood. An eerie grin was slashed along the edges of her mouth.

Harnisch has studied the case off and on for twenty-four years. He has interviewed more than one hundred-fifty people, ranging from the first officer on the scene, to family members of Short, to a former boyfriend, to detectives assigned to the investigation, to the woman who discovered the body. The office in his small South Pasadena home is crammed with five metal file cabinets, twenty boxes of file folders, and four bookcases lined with hundreds of books, all focused on the Short homicide or Los Angeles history. Harnisch is writing a book about the case, but the homicide and the investigation are only part of his focus. His research began when he was a copy editor at the Los Angeles Times and he was writing a 1997 fiftieth anniversary story on the killing. He had so much additional material that when the story ran, he decided to write a book. After three drafts, engaging in countless online battles with people writing about the case whom he constantly fact-checks, and struggling to find a publisher, there are days, he says, when he wished he never heard of the case. His initial outline for the book was narrowly focused. He simply wanted to tell a good crime story and to create an accurate biography of Short, tracing her life from small town Massachusetts, to California, to her death. He never imagined that he would unearth a murder scenario and a suspect who would intrigue LAPD detectives.

Harnisch did not grow up in Los Angeles with iterative reminders of the Dahlia case. He was raised in Illinois and Arizona and moved to Southern California when he was hired by the Los Angeles Times. In the summer of 1996, he was conducting research for a detective novel he intended to write and was looking for a “random, nasty old crime” he could employ as a plot device. During his search he recalled reading something about the Black Dahlia years earlier. He didn’t know her name and this was the pre-internet days, so he couldn’t simply Google her. After conducting some initial research at a local library, he realized that the fiftieth anniversary was coming up in January. He passed along the tip to a Times assistant city editor, expecting him to assign the story to a reporter. The editor, however, asked, “Do you want to do it?” Harnisch, who had always wanted to be a writer, responded, “Hell, yeah.”

At the Times morgue, he obtained all the clips on the case, photocopied them, and placed them in chronological order. The editor wanted “a noir stroll through the clips,” but after perusing the articles, Harnisch realized that boilerplate anniversary stories had been written by reporters on previous anniversaries. “Doing another story like that didn’t interest me. I decided to do the story like it was breaking news, like a second day story. I decided I’d report the story; I’d go out and interview people.”

To know who to interview, he needed to conduct more research. He visited the downtown library and photocopied all the microfilmed Dahlia stories from the three other major newspapers in Los Angeles at the time—the Examiner, the Herald-Express, and the Daily News. After creating a roster of everyone named in the stories—detectives, patrol officers, suspects, family members, witnesses, and reporters—he created a list of people to interview. Again, this was before online searches were possible, so he had to scour voter registration records, Department of Motor Vehicles databases, telephone books, newspaper clips, and other sources. He eventually pared the list down to about a dozen of the people he believed were the most important to interview. Then he had to determine who was still alive

Norton Avenue crime scene, LAPD files.

Norton Avenue crime scene, LAPD files.

After tracking down and interviewing Betty Bersinger, the woman who found the body on Norton Avenue in South Los Angeles, Harnisch discovered that one of the first myths that had accreted around the Dahlia story did not match the reality. Jack Webb, who created and starred in Dragnet, wrote The Badge eleven years after the murder, one of the first books that chronicled the crime. “Along a dreary, weedy block without a house on either side, a housewife was walking to the store with her five-year-old daughter, scolding her a little because she wanted to play in the dew-wet lots. Halfway up the block, the mother stopped in horror at something she saw in one of the lots. ‘What’s that?’ the child asked. The mother didn’t answer. Grabbing her hand, she ran with her to the nearest neighbor’s house to call the police.” Bersinger told Harnisch a different story. Sitting at her kitchen table, he felt disoriented by the juxtaposition of this sweet elderly woman who proudly displayed drawings emblazoned with “I LOVE GRANDMA” on her refrigerator, recounting how she stumbled upon the mutilated body. At about 10 a.m., she was pushing her three-year-old daughter in a stroller—not just any stroller, but a Taylor-Tot stroller, she was proud to point out—to a repair shop to pick up her husband’s shoes. Bersinger and her husband had recently purchased their home for $11,000 in a middle-class neighborhood of primarily newly married couples with young children. She was heading south on Norton Avenue, negotiating the shards of broken glass on the sidewalk that lined the vacant lots.

“I glanced to my right and saw this very dead, white body,” she told Harnisch, her voice cracking. “My goodness…it was so white. It didn’t look quite…like anything more than perhaps an artificial model. It was so white and separated in the middle. I noticed that dark hair and this white, white form.”

“I glanced to my right and saw this very dead, white body,” she told Harnisch, her voice cracking. “My goodness…it was so white.”

Short was face up, her gray-blue eyes were open, and she had been posed with elbows bent at right angles, her hands over her head, and her legs were spread with her knees straight. The pathologist concluded that she had died from blows to the head and the loss of blood from the gashes in her face. The chunk of flesh that had been sliced from her thigh was later discovered to have been a rose tattoo. Harnisch asked Bersinger a follow-up question, but she refused to answer and said she would only tell him the story once. The memory was too disturbing.

“Right from the beginning, this shows you the force of folklore,” Harnisch says. “Webb’s story is like a mini-morality tale: A little girl doesn’t listen to her mommy and makes this horrible discovery. People thought because Jack Webb was tied into the LAPD it was all true. Nobody can tell this story straight.” Harnisch scowls and grips his knees. “Everyone wants to fuck with it.”

Some writers claimed she was lured to Hollywood from the East because she was an aspiring actress. She wasn’t. Others wrote that the newspapers gave Short the sobriquet. They didn’t. A few have intimated she was a hooker. She wasn’t. Or that, at the very least, she was promiscuous. She wasn’t. Some writers contended the original detective team was inept. They weren’t. She’d been called a war widow. She wasn’t.

Will Fowler, a reporter for the Examiner at the time, told Harnisch that he had been the first reporter at the scene and had arrived before the police. Fowler claimed there were no officers to prevent reporters and photographers from tromping through the crime scene and interfering with the evidence. Shortly before police arrived, Fowler, who wrote a memoir, Reporters, told Harnisch that he had closed Short’s eyes and later helped load the bottom half of Short’s body into the coroner’s vehicle. Later, Harnisch tracked down retired LAPD patrol officer Wayne Fitzgerald who, along with his partner, were the first cops on the scene. He contradicted almost every element of Fowler’s account. During an interview Fowler quoted Napoleon: “History is an agreed upon lie.” Fitzgerald contended that when he arrived there were no reporters or photographers.

“The first thing we thought was that it was a mannequin, that someone was playing a trick on us because there was no blood,” Fitzgerald told Harnisch. “Then we realized what the hell we had. We started calling all our supervisors, telling them this was something big.”

Harnisch created a timeline of when reporters, photographers, and detectives arrived by studying the shadows on the crime scene photographs. On January 15th, the date the body was discovered, he jammed a broomstick into the dirt on his front yard, spread out a large sheet of paper, and with a felt tip pen traced the progression of the shadows—a primitive sun dial—and compared them to the shadows in the photos to garner a rough idea of who was at the scene and when. After encountering these early erroneous accounts, he vowed that everything he wrote would be exact, backed by authenticated sources, and he ended up spending an inordinate amount of time, which stalled his own research and writing, challenging the accounts of other writers. He is grateful he began his research decades ago, long before the case generated renewed interest in the Twenty-First Century, because many of those he interviewed are now dead.

About a dozen patrol officers, sergeants, command officers, and detectives descended upon the scene, in addition to numerous reporters and photographers. This was one of the last big stories in Los Angeles pre-television and the competition among the four papers drove the coverage. There were more than a half-dozen editions a day and editors prodded reporters for scoops so editions could be updated. Daily News reporter Jack Smith, later a revered Los Angeles Times columnist, wrote that the frenzied coverage was “The Front Page come to life.”

“I happened to be working on the rewrite desk of the Daily News that morning and drew the story when our police beat phoned in the first bulletin,” Smith wrote in a column years later. “Within the minute I had written what may have been the first sentence ever written on the Black Dahlia case. I can’t remember it word for word, but my lead went pretty much like this: ‘The nude body of a young woman, neatly cut in two, at the waist, was found early today on a vacant lot near Crenshaw and Exposition Blvd.’ I tore the copy out of my typewriter and took it up to the city editor, who was eager to get the story moving into type. He raced through the two lines, pencil poised, and wrote in a single word.” Smith later discovered that the editor, who had no idea what Short looked like, added “beautiful” to describe the victim.

Examiner reporters were the most aggressive and their unorthodox and often unethical approach led them to uncover leads before the detectives. They even aided the police in determining the identity of the victim. Detectives had planned to mail her fingerprints to the FBI in Washington, but an Examiner editor suggested using the paper’s “Soundphoto” machine, which was similar to a fax, to transmit the fingerprints to the Hearst Washington Bureau and then hand deliver them to the FBI. Examiner reporters and detectives discovered that Elizabeth Short’s prints were on file because she had applied for a clerk job at Camp Cooke in California during World War II and had been arrested by Santa Barbara police for underage drinking.

Once Short was identified, reporters scurried to find out as much about her as possible—on deadline. An Examiner rewrite man, Wain Sutton, used a heartless tabloid ploy to obtain background. As City Editor Jimmy Richardson sat in a swivel chair beside him, Sutton called Short’s mother, Phoebe, and said that her daughter won a beauty contest in Southern California. The late Pulitzer Prize-winning sports columnist Jim Murray was a rewrite man for the Examiner at the time and sat next to Sutton. He told Harnisch in an interview that he was “still appalled” and the “incident was sharply etched in his memory.”

“Wain called the mother and asked all these questions and took all these notes,” Murray recalled. “I sat there and listened to the poor, dear mother telling him about her school-day triumphs. I can still see him put his hand over the mouthpiece of the old-fashioned upright phone and say, ‘Now, what do I tell her?’

“Richardson screwed up his one good eye and said, ‘Now tell her’

“’You son of a bitch,’” Murray said, imitating Sutton.

Still, Short’s mother refused to believe her daughter was dead. When police officers from her small Massachusetts town showed up at her front door, after the LAPD contacted them, she finally accepted the grim news.

Examiner reporters beat police to the locations where Short had stowed all of her belongings shortly before she was killed. Reporters interviewed an acquaintance of Short and discovered that she had checked luggage that contained all her belongings at a bus station in Los Angeles. Richardson informed Jack Donahoe, the head of LAPD’s Homicide Squad about his finding and said he would tell him where the suitcases were—under one condition. He wanted the cops to open them at the Examiner office. Donahoe balked. Richardson responded: “No deal, no suitcase.” Donahoe reluctantly agreed, Richardson wrote in his book, For the Life of Me. At the Examiner, detectives opened the trunk, which contained Short’s clothes, photos of her, and letters from boyfriends, which the paper printed. Reporters and detectives raced to track down the boyfriends identified in the letters. During World War II, crime surged in L.A. and generated such interest that the Examiner ran a daily tally on the front page. On the day Short’s body was discovered, the paper reported two murders, thirteen robberies, and forty-seven burglaries.

The FBI, who had been called into the case to provide forensic assistance, noted in their files the problematic behavior of the reporters. “Throughout the entire investigation, the reporters have talked to witnesses and published facts which were bound to hinder the investigation of the local department,” the agent in charge of the FBI’s Los Angeles office wrote to the director. “Reporters are at the Detective Bureau and it is not possible for the investigators to have confidential telephone conversation or even read mail without having some news reporter looking it over to see if it relates to this one.”

Ten days after Short’s body was found, the killer mailed an envelope of Short’s belongings to the Examiner. Using letters clipped from a page of movie ads, he addressed the envelope. Possibly as a taunt to the detectives, he included the phrase: HEAVEN IS HERE! The envelope included Short’s birth certificate, Social Security card, newspaper clippings, and a ten-year-old address book, which listed seventy-five men. Police launched a massive search and tracked down many of them, but most only knew her briefly and the search yielded nothing significant. They were unable to obtain fingerprints from the envelope because it had been brushed with gasoline. Other letters from senders who claimed to be the killer were delivered to the LAPD and the papers, but they were never authenticated.

Detectives were also inundated with dozens of false confessions during the first few months after the murder and they interviewed a steady stream of men—and a few women—who claimed to be the killer. A former member of the Women’s Army Corps told detectives, “Elizabeth Short stole my man so I killed her and cut her up.” One confessor was asked by skeptical detectives to pick out Short from a series of photographs. He could not and then tried to stagger off. Detectives threw him in the drunk tank.

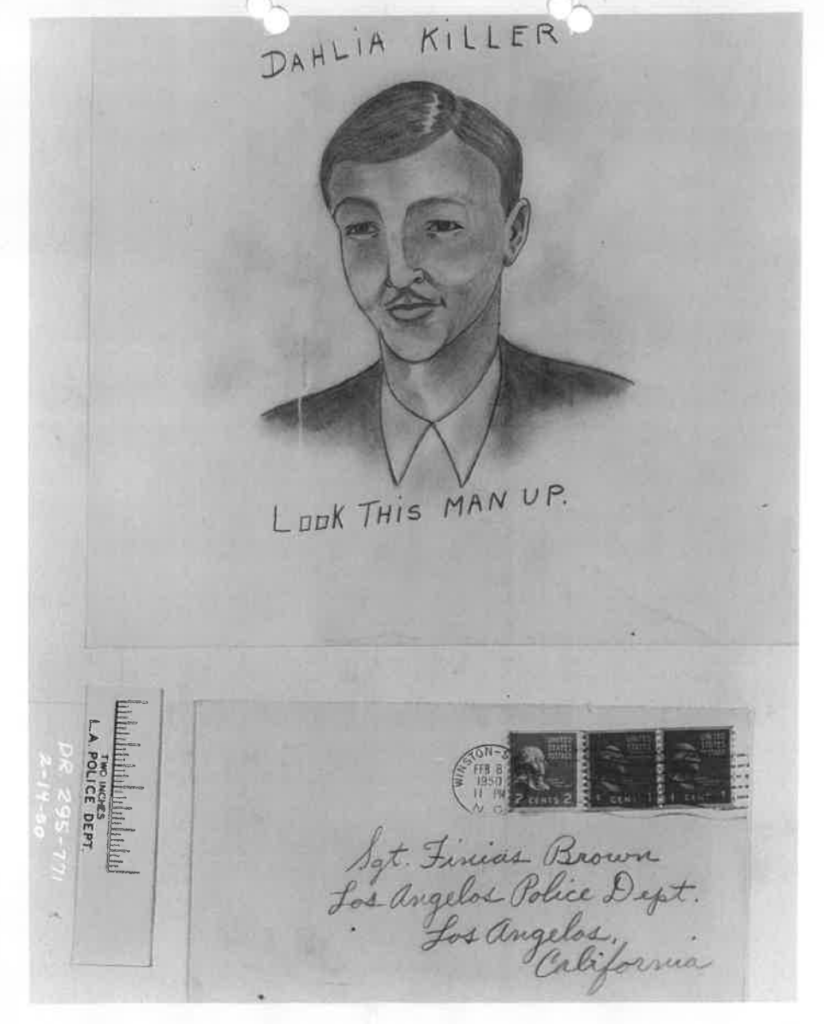

Public tips in Black Dahlia case, LAPD files.

Public tips in Black Dahlia case, LAPD files.

Among authors, the case has resonated for decades. John Gregory Dunne employed a fictional account of the Dahlia murder in his 1979 novel True Confessions, which portrayed the victim as a prostitute. Dunne and his wife, Joan Didion wrote the screenplay for the movie, which starred Robert De Niro and Robert Duvall. After experimental film director Kenneth Anger’s book Hollywood Babylon II, was published in 1984, featuring lurid crime-scene photos that exposed the grotesque nature of the crime to a new generation of readers, it created wide-spread interest in the case. Best-selling author James Ellroy was eleven—eight months after his mother was murdered—when he received a copy of The Badge as a birthday present from his father. He read the Dahlia section more than a hundred times, he wrote in his memoir My Dark Places. His obsession with the case culminated in his 1986 novel, The Black Dahlia, which hinted that the victim was involved in stag films. The book was made into a widely-panned Brian De Palma film. The Dahlia case helped Ellroy cope with his own tragedy and his frequent nightmares, he wrote, enabling him to experience the horror and grief over Short’s killing that he hadn’t been able to express over his own mother’s murder.

“He’s a journalist, he lets the facts guide him, and he doesn’t have any agenda other than the truth.”

Anne Redding, chair of the Justice Studies Department at Santa Barbara City College, has researched the homicide for more than thirty years and uses it as a centerpiece in her Study of Murder class. She became increasingly frustrated by the all the sloppy analysis, bogus theories, and inaccuracies surrounding Short’s life and death. She began following Harnisch’s blog about the case, which he launched after writing the anniversary story, and was immediately impressed. “It was so refreshing to find someone who was sticking to the facts and the original documents,” she says. “He’s a journalist, he lets the facts guide him, and he doesn’t have any agenda other than the truth. I haven’t seen anyone come close to what he’s done. I believe he’s the single most authoritative expert on the case.”

Harnisch spent three decades as a newspaper copy editor, ensuring stories contained no inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and were grammatically correct, and he brings this punctilious approach to his Dahlia research. When asked about an element of the investigation, he is often reluctant to answer, and instead says, “Let me check my files.” He then lunges out of his chair, disappears into his office, roots through the photocopied newspapers clippings, inquest reports, and investigative files, and returns with a precise answer. An intense man who chooses his words carefully, he wears wire-rimmed glasses, has neatly parted gray hair, and a high forehead that dissolves into furrows when discussing the many myths and mistakes promulgated by writers. He lives in a house befitting a man immersed in the past. The living room in his 1910 bungalow is cluttered with his great-grandmother’s china cabinet and mirrors; his grandfather’s tool chest, which he uses as a coffee table; his mother’s piano; a Maxfield Parish lithograph that his grandfather gave his grandmother when they married; and on the mantle his grandparent’s candelabras and an antique German wind-up clock.

As Harnisch delved deeper into Short’s murder, he wanted to make a donation on her behalf and consulted family members. They recommended Heading Home, a Boston emergency shelter for homeless women and low-income families. Now every January 15th he sends a check. He also spends the evening wandering around the lobby of the Biltmore Hotel, where Short was last seen, paying homage to her and ruminating about the case. Several times, Harnisch visited her grave in Oakland and left flowers.

“What keeps me going is that I promised myself I would clear up all the lies and myths and try to reclaim Elizabeth Short from the Dahlia freaks. I feel a responsibility. The family has gone through so much and all writers have ever done is rip them off. They deserve to have somebody tell the story accurately. That’s the least I can do for them and for Elizabeth Short, someone who changed my life.”

***

When Harnisch began researching his book, he had no interest in attempting to solve the murder. Those who claimed to have identified the killer, he felt, were deluded. He made a discovery, however, that altered his perspective.

During his reporting for the fiftieth anniversary story he interviewed legendary FBI profiler John Douglas. In recent years, the efficacy of profiling has been called into question, but in the 1990s, many considered it a valuable investigative tool. Douglas asked Harnisch what he knew about the neighborhood. Harnisch didn’t know much, but he thought it was an interesting question. Douglas explained that the street where the body was dumped was a curious choice for the killer. Although the block had not yet been developed, there were houses nearby. In a half hour, the killer could have transported the body to the beach or the mountains; add another half hour and he could have reached the vast expanses of the Southern California desert. Instead, he left the body in a busy residential area. “Someone is going to look out a window and see you,” Douglas told Harnisch. “You’re going to get your ass caught.” Douglas speculated that the killer wanted to shock and horrify the residents, sending the message that Short was a slut. The killer, Douglas surmised, had some connection to the neighborhood.

After the article ran and Harnisch began researching the book he intended to write, he was haunted by Douglas’ supposition, so he embarked on a search to find out everything he could about the 3800 block of Norton Avenue and the surrounding neighborhood. He hoped to discover the link between the killer, the crime scene, and the neighborhood. Harnisch decided to start from the beginning, when the area was part of a Spanish Rancho—Rancho La Cienega o Paso de la Tiejera. He read a history of the ranch and interviewed a group of scholars at Cal Poly Pomona who had conducted a detailed study of the area’s architecture and history. In addition, he met with Walter Tim Liemert, the son of the man who developed the housing tract, located in the neighborhood named after him—Liemert Park. At the city archives, he spent months searching for information about the area, studying Police Commission meetings from the 1930s and 1940s, and perusing all the city paperwork centered on the neighborhood. Harnisch discovered that mob boss, Jack Dragna, lived four-and-a-half blocks from the crime scene, so he had to determine if there was an organized crime connection to the murder.

If he ever encountered anything significant, he believed that it would “stand out like a beacon.” Nothing related to Norton Avenue did stand out, however, but he was not discouraged.

“I absolutely love research,” he says. “I’d rather research than eat. Although I’d uncovered nothing significant, I found all this L.A. history fascinating.”

When a Dahlia enthusiast heard about Harnisch’s investigation, he sent him a box filled with photocopies of newspaper articles about the crime, a transcript of the inquest that contained most of the autopsy notes, a homemade documentary, a copy of Short’s grades from elementary school, and a dim photocopy of the marriage certificate of her oldest sister, Virginia Short. Nothing seemed significant, so he forgot about it. During the summer of 1997, his family was out of town, so he had some extra time to take a more thorough look at the contents of the box. When he studied the marriage certificate, he discovered the couple was married in Inglewood. Harnisch perked up when he noticed that a witness to the ceremony listed an address that looked like Norton Avenue, but he wasn’t sure because the certificate had been photocopied numerous times and was smudged and hard to read. The original was filed in Sacramento, the state capital, so Harnisch, still not wanting to get his hopes up, sent a check and ordered a copy. About a month later, while he was talking to his wife during a break from his copy editing duties, she told him he had received a letter from the state. He asked her to open it up and tell him the name of the street the witness, Barbara Lindgren, listed. “Norton Avenue,” she told him.

Harnisch pulls a dusty cardboard box out of his office, fishes out a Manila folder, removes a copy of the marriage certificate, and points to address—3959 Norton Avenue. “That’s only a block from where Short’s body was found,” he says, running his finger along the address. “This was a component nobody had ever looked at. Although I wasn’t quite there yet, this was definitely interesting. Now everything depended on finding out who was Barbara Lindgren.”

Harnisch now had a connection between a witness to Virginia Short’s wedding and the crime scene. He wanted to interview Short and her husband in an attempt to determine the identity of Barbara Lindgren, but they were dead. The clips at the Times and phone book directories from the 1940s were no help in locating Lindgren. Finally, he spent afternoons in the dim subbasement of the Los Angeles County Hall of Records, leafing through plat books where property deeds were recorded. This is where Jake Gittes in the movie Chinatown discovers that a civic kingmaker has been surreptitiously buying up San Fernando Valley scrubland for rock-bottom prices because he has insider knowledge that the land will soon be worth a fortune when an aqueduct brings water to the area, enabling the property to be developed. Harnisch found the books for the 3900 block of South Norton Avenue and he worked his way through them until he reached the 1940s. Eventually, he found the owner of the house on 3959 Norton Avenue, the woman on the deed who paid the property taxes—Ruth Bayley. Hurrying to the Times morgue, he searched the clips for Ruth Bayley and what he eventually found shifted his role—from writer to sleuth.

***

The marriage certificate indicated there was a link between the Short family and South Norton Avenue. From studying the microfilmed Times clips he discovered that Ruth Bayley, who owned the house, had a daughter whose married name was Barbara Lindgren. She was the matron of honor at the wedding of Elizabeth Short’s oldest sister in Inglewood. A story about Ruth Bayley’s husband revealed something even more interesting to Harnisch—Ruth had been married to Walter Bayley, a Los Angeles doctor, a surgeon with the skill to have performed the bisection of Short. And his medical office, where he specialized in performing hysterectomies and mastectomies, was only a few blocks from the Biltmore Hotel. The lead detective on the case, Harry Hansen, told the Grand Jury that he believed that Short’s killer had surgical expertise.

Removing a cardboard box from his office, Harnisch searches for Hansen’s Grand Jury testimony. Flipping through files—muttering, “Hansen, Hansen, where is Hansen?”—he locates a folder, fishes out testimony, and points to the relevant passage. Hansen tells the jurors that he had worked cases where bodies were mutilated and bisected but the Short murder was different.

“I have a little pet theory of my own. I think that a medical man committed that murder. A very fine surgeon. I base that conclusion on the way the body was bisected….It is unusual in the sense that the point at which the body was bisected is, according the eminent medical men, the easiest point in the spinal column to sever…he hit it exactly.”

John “Jigsaw John” St. John was assigned the Dahlia file after Hansen retired and he kept control of the case until he pulled the pin in 1993. I shadowed him on his last day on the job when I was a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, and during lunch at a dim, smoky steakhouse near downtown, I asked him about the Dahlia case. St. John, who wore Badge No. 1, spent 43 years as a homicide detective and investigated more than 1,000 murders and twelve serial killers. He sipped his V.O. and water and told me that he did not believe the person who committed the murder was a serial killer. His “signature” was unique he told me, combining a number of homicidal elements that he had not been seen since the murder. Some of those elements, he said, have never been revealed by detectives in order to weed out the false confessors. The real killer, he believed, only killed once.

As Harnisch was fruitlessly attempting to track down Barbara Lindgren, he ventured to create as thorough a biography of Bayley as was possible in those days before genealogical websites and online searches. The clips revealed that Bayley had left his wife and family in 1946 because of his burgeoning relationship with a female physician he worked with, Alexandra Partyka. Harnisch could not interview Partyka, Bayley, or his wife because they had all died, so he ended up talking to numerous retired doctors who had either attended medical school with Bayley at USC or worked with him at Los Angeles County Hospital, and later researched his years as a surgeon in France during World War One. And because his will was contested, Harnisch was able to study the probate files from the Hall of Records, which listed the contents of his office, down to the serial numbers of his typewriters, and all of his debts.

Harnisch removes from his files a 1948 Examiner article on the dispute over Bayley’s will and shows it to me. “Intimidation by a young woman colleague caused Dr. Walter A. Bayley, physician, to disinherit his wife, the widow Mrs. Ruth A. Bayley, she claimed yesterday in a will contest suit, filed in Superior Court. Mrs. Bayley, who lives at 3959 South Norton Ave., asserts that while associated with Dr. Bayley in practicing medicine, Dr. Partyka threatened to expose and ruin him if he returned to his wife.”

Former colleagues and relatives expressed to Harnisch how shocked they were at how Bayley’s personality drastically changed toward the end of his life. An interview with Bayley’s former secretary was of particular interest. She told Harnisch that she was stunned that Bayley and Partikya used to pick up dinner to go, listen to classical music at their medical office, and eat dinner while watching surgery films. This interview and the Examiner article galvanized Harnisch.

“Now I find out he had some kind of secret and lived in constant fear of being exposed. And he spends his evenings watching surgery films. That’s off the charts weird. Now I feel I’m on the right track.”

Harnisch obtained Bayley’s death certificate and one of the causes of death is listed as encephalomalacia. He wrote to medical school professor, a board certified psychiatrist, the author of an article in a psychiatric journal on the condition, and related what he knew about Bayley and the Dahlia murder.

“Enchephalomalacia is a structural lesion in the brain…softening of brain tissue,” the psychiatrist wrote to Harnisch. “The location of the lesion and the cause as well as when it occurred can have a significant impact on the behavioral manifestations caused as a consequence of the lesion. There are people with this lesion without any psychological pathology, and there are others who have significant pathology which may include bizarre violence…”

On a recent evening, Harnisch visits Dr. James Fallon, a professor emeritus of neurobiology at the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine, tells him about Bayley’s shift of personality and presents the psychiatrist’s assessment. Fallon, who is familiar with the Elizabeth Short murder, agrees that the location of the lesion is the key. As they discuss the case, they reveal antipodal personalities. While Fallon has an ebullient mien and manner, clearly enjoys discussing the bizarre nature of the case, and asks if Harnisch has explored his book’s movie potential. Harnish, solemn and staid, appears offended, and tells Fallon he’s not interested and wouldn’t allow a film to be made “that treated Short like a piece of meat.”

Fallon returns to the subject at hand and asks Harnisch if he has a copy of the autopsy notes or knows the section of the brain where the lesion was identified. If the autopsy had been conducted by the Los Angeles County Coroner, Harnisch says, he could have obtained a copy because it’s a public record, but a pathologist at the Veteran’s Administration conducted the postmortem. Federal documents, he tells Fallon, are much more difficult to obtain, the V.A. refused his request, and all he has is the death certificate.

Bayley’s lesion and drastic personality change could be the result of, “Frontotemporal dementia from a series of little strokes,” Fallon says. Frontotemporal dementia primarily affects the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. “With this condition you could see a radical change in personality,” says Fallon, who has written extensively about the neural circuitry of criminal behavior. “The drive for violence and sexuality can come up and get worse and worse. But it wouldn’t necessarily affect his sensory or motor skills and he could still do surgeries. So, the pathology lines up.”

The probate records revealed, Harnisch says, even more significant clues. When I asked him to explain, he hesitated and then refused. “This is one thing I have that nobody else has. I don’t want other people following my trail. I’ll just say it was very helpful.”

When he finally tracked down Barbara Lindgren, his initial investigation into Bayley was almost complete. Lindgren told Harnisch how scandalized the family was when her father left them for Partyka. The drastic personality shift at the end of Bayley’s life “wasn’t anything I could have ever dreamed of happening,” she told him. When he asked her about Elizabeth Short, she became wary. She agreed to serve as the matron of honor at Short’s sister’s wedding, she told Harnisch, “because there wasn’t anybody else.” When he suggested that such a role indicated a close level of friendship, she was very dismissive and refused to elaborate. He asked if her mother ever discussed the murder of Elizabeth Short and Lindgren said she had never mentioned it. At the end of the conversation, she implored Harnisch in an anguished tone not to tell anyone how to find her.

“This seemed very strange,” Harnisch says. “The story was such big news, the body was found down the street from her mother’s house, and the family knew Short’s sister. Her reaction seemed too defensive, too rehearsed. It was like she was waiting for someone to ask her about Elizabeth Short and she had a pat denial ready.”

“The story was such big news, the body was found down the street from her mother’s house, and the family knew Short’s sister.

Harnisch had a series of building blocks that led to a viable suspect; now he had to stitch them together and create a plausible scenario. This is what he theorized: Lindgren was the matron of honor at the marriage of Virginia Short and Adrian West, who Harnisch learned quite a lot about from interviewing their son, Elizabeth Short’s nephew. West was the ultimate boy scout, Harnisch says, a devout Presbyterian. He and his wife knew the Bayley family well and Harnisch surmises that when Elizabeth Short, who had been couch surfing and virtually homeless for the past year, had been dropped off at the Biltmore Hotel, after a sojourn in San Diego, with no place to stay and little money, she might have recalled some advice from West or her sister.

“They might have said if you’re ever down and out in L.A. and need help, call the Bayley family. That’s the kind of thing Adrian West would have done. He was always trying to help people. Short might have called Barbara Lindgren, but she had recently moved to the Midwest. So, then she might have called Walter Bayley, who was listed in the phone book, and they could have ended up in his office, which was a short walk from the Biltmore.”

Elizabeth Short, archival.

Elizabeth Short, archival.

Harnisch adds one more variable to his hypothesis. The profiler, John Douglas, speculated that the killer was probably angry at some residents on Norton Avenue and intended “to put the fear of God into that neighborhood.” Harnisch recalled this when he learned that Bayley had adopted two girls and then had one biological son whom he doted on and who’d been killed. In 1920, the son was riding a bike when he saw his younger sister was about to step off the sidewalk. He rode toward her, to prevent her from wandering into a busy street, when he was hit by a truck. His father was devastated. “Walter was our only son—the only child of our flesh and blood,” Bayley said in a newspaper story. “Our hearts and soul were wrapped up in him…I have seen much of death—but I never understood it before.” A few years before his death, Bayley disinherited the two people living on 3959 South Norton Ave—the daughter who Bayley might have blamed for his son’s death and his estranged wife, who was supposed to supervise the girl. Bayley’s son was killed on January 13 and Short might have been killed on that exact date, Harnisch says, because she disappeared on January 9th and her body was found on January 15th.

“If she met him on the pretext of getting help, she would have pulled the sob story about having a son who died. Unlike the other pigeons she was trying to con, he would have actually asked how he died because he was a doctor. So now they both have something in common—dead sons. Maybe he figures out she’s lying, it pissed him off, and he erupts…”

On a recent sunny afternoon, Harnisch takes me on a stroll down Norton Avenue to illuminate some of his claims. We start at the house of Betty Bersinger, the woman who found the body. The neighborhood was all-white in 1947, but now is predominantly African American with some Japanese residents who have sculpted bonsai trees in their front yards. The homes are well kept, the lawns trimmed, and the shrubbery pruned. We follow Bersinger’s path, from her gray stucco house with a postage stamp front lawn, down the sidewalk to the lot where Short was found. At the time, the street was undeveloped because the war had stopped construction, and Short was found on an empty lot, but now at the location there is a beige stucco house with Italian cypresses shading the lawn. We walk one more block to the home where Bayley’s estranged family lived at the time, a single story home with gravel instead of a front lawn, edged with purple and yellow lantana, and a broad front porch.

I’ll never say I’m a hundred percent sure. I still don’t have all the details I’d like and I’m still hoping to get more.

“As you can see,” Harnisch says, “it’s an easy walk from the crime scene to Walter Bayley’s house—only one block. So, it’s clear that Bayley has a connection to the street where Short is killed. The Short family and the Bayley families know each other. He’s a surgeon with mental problems who underwent a drastic personality shift. He had the strange habit of watching surgery films at night. He has a secret and lived in constant fear of being exposed. I’ll never say I’m a hundred percent sure. I still don’t have all the details I’d like and I’m still hoping to get more. But it makes a neat package, doesn’t it?”

In the 2001 documentary James Ellroy’s Feast of Death, Harnisch presents his theory of the case during a dinner hosted by Ellroy, who has studied the murder for decades and has an encyclopedic knowledge of L.A. crime. He called Harnisch’s theory “the most plausible explanation of the murder “that I’ve heard…the theory is great. It’s just about watertight in most ways.”

LAPD Detective Brian Carr, who was in charge of the Dahlia case at the time, was more equivocal at the dinner, but still found all the coincidences relating to Bayley and the murder intriguing. “And when you run into coincidences in a homicide investigation, you want to go, ‘Wait a minute.’ And that’s what it made me say, ‘Wait a minute.’”

Rick Jackson, who spent a decade in LAPD’s elite Robbery-Homicide Division and was the assistant officer in charge of the department’s Cold Case Unit before he retired, is familiar with Harnisch’s theory. He also said the coincidences piqued his interest. “The location between the Bayley house and the crime scene, his medical ability, his obsession with watching surgery films, and some other things Harnisch came up with make Bayley an interesting suspect. Harnisch doesn’t have the smoking gun, but his theory definitely has to be included in the most likely theories.”

***

In 2003, Harnisch was sanguine about his book. He had almost completed his second draft, Ellroy was interested in writing the introduction and was going to set up him up with his agent. Then another book, Black Dahlia Avenger, was released that “blew everything out of the water,” Harnisch says. The author, Steve Hodel, who fingered his father as the killer, wasn’t the first writer to make this claim. Janice Knowlton, author of Daddy was the Black Dahlia Killer, based her assertion on repressed memories that had recently surfaced. Mary Pacios who grew up near Short in Massachusetts and wrote Childhood Shadows, suggested that Orson Welles, who appeared to saw a woman in half during a magic trick, was the killer. While these authors could be easily dismissed, Hodel’s background gave him immediate legitimacy—he is a retired LAPD homicide detective. His father, George Hodel Jr., was a dashing physician who hobnobbed with actors and artists, lived in a house designed by Lloyd Wright, Frank Lloyd Wright’s son, in Hollywood, and operated a downtown venereal disease clinic. Hodel’s investigation began when he was retired and living in the Pacific Northwest. He was given his father’s photo album shortly after his death, which was filled with pictures of family and friends, including several unidentified women. Two of the photos, he was convinced, were of Elizabeth Short. This launched Hodel’s investigation. He discovered that two years after the Short murder, George Hodel was tried for molesting his 14-year-old daughter, Tamar. She also claimed that nineteen other people, including many of her classmates, had molested her. Testimony during the trial revealed that she had previously accused her father of killing Short. Tamar’s mother, however, testified that a psychiatrist had told her that her daughter was addicted to telling “fantastic stories. He described her as a pathological liar.” The jury acquitted the doctor.

In addition to Short, Hodel claimed in the book that his father also killed Jeanne French a month later, which was called by the newspapers the Red Lipstick Murder because of the writing on the body. As a result of wide-spread corruption in the LAPD, Hodel claimed, the murders were covered up and never solved. Hodel’s book contains numerous assertions about his father and the Dahlia case, some that are authenticated, some that are speculative; nonetheless, the book received widespread attention and immediately eclipsed Harnisch’s theory. Black Dahlia Avenger was soon a commercial success—a New York Times bestseller—but the reviews were mixed. In Los Angeles, the book was savaged.

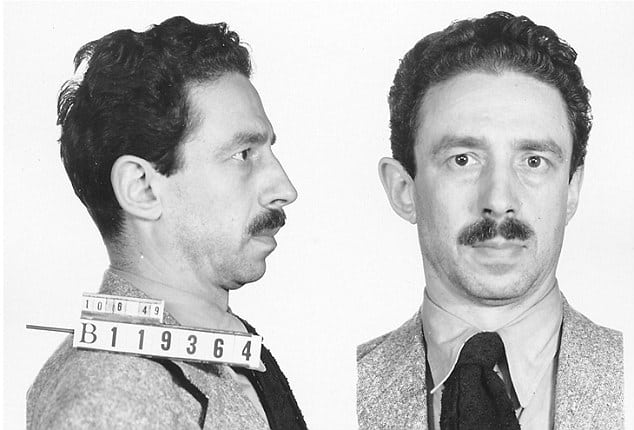

Black Dahlia suspect, George Hodel, LAPD.

Black Dahlia suspect, George Hodel, LAPD.

A Los Angeles Times reviewer called the book a “piece of meretricious, revolting twaddle, which amounts to evidence manufacturing…” The reviewer for the L.A. Weekly wrote, “Why would a retired LAPD homicide detective with twenty-four years of experience write such gobbledygook.” A Washington Post writer was the only one to mention an alternative theory of the case: “A more likely scenario, however, is the one put forth by Larry Harnisch. His research takes us to a deceased surgeon named Walter Bayley. He had family connections to Elizabeth Short: his daughter knew Elizabeth’s sister and brother-in-law. Bayley had an office a few blocks from the Biltmore Hotel, the last place where Short was seen alive. Harnisch argues that Short, destitute and alone on a cold January evening, sought refuges in his company. At the time, Harnisch, says, the surgeon was suffering from a severe form of dementia. Harnisch further speculates that after killing her, Bayley placed Short’s body a mere 45-second walk from the house where his estranged family lived, because he wanted to frighten and intimidate them. …Steve Hodel completely dismisses Harnisch’s theory in Black Dahlia Avenger. Yet the loose chain of circumstance he assembles to prove his father’s guilt is less convincing still. It may well be that, barring the dramatic appearance of a written confession, the Dahlia will remain the stuff of Angeleno myth.”

The two photos Hodel was convinced was Short, the photos that launched his investigation, were soon called into question. Detectives in the LAPD’s Cold Case Unit said the photos bore no resemblance to Short. Harnisch, who was in touch with the Short family, received an email from one of her sisters who saw the pictures in a magazine article about Black Dahlia Avenger, and stated they were certainly not Short. Hodel later acknowledged that that one of the pictures was of someone else, but still insists the second photo was Short.

Hodel recently talked to me about the book during lunch at a restaurant perfectly in tune with the city’s infamous noir-era homicide—Hollywood’s Musso & Frank Grill’s, opened in 1919, which still serves dishes that were on the menu when Short was murdered: grilled calves liver, Welsh rarebit, liver and onions, lamb kidneys, and oyster stew. A hefty man with a white mustache and goatee who is wearing a Panama hat, Hodel reflects on the painful period after the release of his book when his integrity was questioned. “It was so partisan,” he says, picking at his chicken pot pie. “It was very difficult to be subjected to all that negative exposure.”

Hodel believes his reputation was salvaged by a surprising revelation by a newspaper columnist and the support of Stephen Kay, an assistant Los Angeles County district attorney. Kay, who had worked with Hodel on some cases when he was a homicide detective, wrote, while emphasizing that he was not speaking for the D.A’s office, “The most haunting murder mystery in Los Angeles County during the 20th century has finally been solved in the 21st century.” If George Hodel were alive, Kay wrote, he would file two counts of murder against him for the Dahlia and the Red Lipstick murders. Kay, however, later insisted that he did not agree with Hodel’s contention of a police cover-up.

When Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez questioned D.A. Steve Cooley about the case, he said that Kay had presented Hodel’s theory in a closed-door presentation, but he “wasn’t close to being convinced.” Still, he allowed Lopez to peruse the previously unreleased 1949 grand jury files, which chronicled an investigation headed up by D.A. Detective Frank Jemison. “I opened a dusty old box, and it was like exhuming a body,” Lopez wrote. “My stomach turned when I came to photos of the corpses of Elizabeth Short…and Jeanne French…Flipping past those photos, a number of smaller mug shots slipped out of the stack, and looking up at me, his eyes dark and narrow, was Dr. George Hodel.

“So, he was a suspect.

“OK, but so were a lot of people. Det. Jemison had compiled a list of 22 suspects, with Dr. George Hodel among them.”

Hodel was initially considered a suspect because Jemison compiled a list of all L.A. doctors who had been accused of sex crimes. The D.A. had bugged Hodel’s home and he was recorded saying, “Supposin’ I did kill the Black Dahlia. They couldn’t prove it now.”

Later in the recording, however, he announces that he is probably being bugged, and Lopez speculates that Hodel was taunting investigators. Jemison wrote in his summary that an acquaintance of Hodel claimed that one of his girlfriends was Short, but added that the informant was later committed to the State Mental Institution at Camarillo. Jemison concluded in his summary: “See supplemental reports…and hear recordings, all of which tend to eliminate this suspect.”

Lopez studied the files and read Hodel’s book, but he remained unconvinced. “Hodel draws sweeping conclusions, but when I began to investigate all I found were shadows…” He never “put the two of them together, let alone prove a murder.” Still, Hodel was elated by the release of the D.A. files. His research, he believed, was redeemed. He appeared on numerous network crime shows, CNN’s Anderson Cooper interviewed him, and he soon eclipsed Harnisch as the go-to guy on the Dahlia murder.

After fingering his father for the two murders, Hodel later claimed he was one of the Twentieth Century’s most prolific serial killers. He attributes at least twenty-five murder to George Hodel, including the eight Northern California Zodiac killings, in addition to homicides in Chicago, Texas, the Philippines and a dozen in Southern California. In five other books Hodel describes his investigation into these killings. He has been unable, however, to interest law enforcement authorities in following up on his claims.

After fingering his father for the two murders, Hodel later claimed he was one of the Twentieth Century’s most prolific serial killers.

After Black Dahlia Avenger was released, the book attracted so much attention, the LAPD brass allowed Hodel to present his theory to the Cold Case Unit. Detective David Lambkin, who was head of the Unit at the time, said that Hodel lost credibility as a result of the numerous other murders he attributed to his father. His evidence was simply not convincing, Lambkin says. In addition, one of the Los Angeles homicides Hodel attributes to his father was extensively investigated by the Unit, Lambkin says; the case was solved, the killer was identified, and he was not George Hodel.

“His dad was one of the suspects in the Dahlia murder, don’t get me wrong, but Hodel went way overboard,” Lambkin says. “If you read the book without delving into it too closely, I can see why you might buy into what he claims. There’s a lot of conjecture, but by the end of the book it’s stated as fact. I still prefer Harnisch’s theory. He doesn’t bring in all this superfluous stuff to prove his case. He sticks to the facts. And the parts fit better.”

The LAPD’s investigative files for the Short murder are stored in a four-drawer metal cabinet located in a locked storage room on the fifth floor of the Police Administration Building. Only the Robbery-Homicide Division captain and Detective Mitzi Roberts, who is in charge of the case, have the keys to the storage room and the cabinet, “which is stuffed to the gills,” she says. Roberts is diplomatic when discussing theories about the case. Harnisch’s theory “makes a lot of sense…I really like it,” she says. And the fact that Hodel’s father was named as a suspect and is mentioned in the D.A.’s files, she says, is intriguing. But without more definitive evidence, she says, the case can’t be cleared.

Ellroy read Black Dahlia Avenger, was impressed by Hodel’s findings, and wrote an introduction to a subsequent edition of the book. Harnisch was devastated. Later, Hodel says, Ellroy “pissed backwards,” recanted his earlier endorsement, and told interviewers, “maybe I was fooled.” I interviewed Ellroy recently for another story I was writing, and we chatted amiably for about twenty minutes. When I asked him if he preferred Harnisch’s or Hodel’s suspect, he snapped, “I won’t talk about that anymore. There are two things I refuse to discuss: Donald Trump and The Black Dahlia.”

Hodel contends that Harnisch’s suspect, Walter Bayley, had a secret, but it wasn’t murder. A self-published book by a former LAPD Vice detective wrote in 1950 that an abortion doctor’s office was located in a building on West 6th Street—the same building as Bayley’s office. Harnisch points out that this was a hulking eight-story medical building devoted entirely to doctors, so just having an office there proves nothing. Bayley was chief of staff at Los Angeles County Hospital and an associate professor of surgery at USC Medical School, and doctors Harnisch interviewed who knew Bayley, as well as his secretary, insisted that it was highly unlikely that a surgeon with his professional standing would have performed abortions.

About the only thing Harnisch and Hodel agree on is the innocence of Leslie Dillon who author Piu Eatwell identifies as Short’s killer in her 2018 book, Black Dahlia Red Rose. Redding of Santa Barbara City College’s Justice Studies Department says that both Eatwell and Hodel “have fallen into the trap of confirmation bias. They cherry pick information to confirm their view of who the killer was.” Dillon had been taken into custody by detectives from the LAPD’s Gangster Squad, claimed he was held against his will, and questioned for days by a police psychiatrist. He later sued the department. Both Harnisch and Hodel say they have no interest in pursuing Eatwell’s theory of the case because the extensive D.A. investigation, which was initiated as a result of the Dillon debacle, placed him in San Francisco at the time of the killing.

***

After all the attention Hodel’s book received and the defection of Ellroy, Harnisch’s best known advocate, he was extremely discouraged. During this time his marriage dissolved, he moved to a small apartment, and he faced the depressing reality of spending holidays away from his wife and son. With neither the energy nor motivation to finish his book, he put it aside. Instead, he began blogging daily about Los Angeles history for the Times, freelancing occasional articles for the paper, and frequently challenging the accuracy of Hodel and other writers on his Black Dahlia blog. While he wasn’t adding chapters to his book, the research for the blogs provided valuable background when he returned to writing five years ago, shortly before he retired from the paper. His first draft, he realized, had been overstuffed, encyclopedic rather than dramatic. On his second draft he changed the point of view to first person, but he later realized the writing sounded too much like a parody of noir. Harnisch had spent most of his career editing other writers, but after all the blogging he had done, he realized his writing had improved dramatically, so he embarked on another draft, which he is attempting to finish as he continues to delve deeper into Walter Bayley’s background. His final task is to chronicle the last few months of Short’s life, and Harnisch has gone to extraordinary length to track down biographical details.

Short, who was only twenty-two when she died, was raised in the Boston suburb of Medford, the third of five girls. During the Depression, her father, who built miniature golf courses, suffered a financial setback and abandoned the family when Short was six. The family was struggling, so during her freshman year she dropped out of high school and worked as a waitress and movie usherette. A neighbor of the family, Bob Pacios, told Harnisch that Short was “by far the prettiest of the five sisters.”

During the war, Short, who had asthma, moved to Florida to escape the harsh New England winters, and met a pilot, Major Matt Gordon Jr. While he was overseas and flying P-51s in the Burmese theater he wrote and proposed marriage. She immediately accepted. Gordon’s mother later told reporters that Short had sent her son twenty-seven letters in eleven days. In August, 1945, five days before V-J Day, Gordon was killed in a crash and Short never overcame her grief.

Harnisch attended a reunion of Gordon’s unit, the 2nd Air Commandos, in Florida and interviewed a number of his fellow pilots. In his office, Harnisch points out a framed photo of Short, who was called Beth at the time, wearing a green beret, a matching top, and a string of pearls. The picture, which is signed: “To T.J. Love and luck always, Beth,” reveals Short’s gracious nature. “One of the pilots at the reunion let me copy this and told me the story,” Harnisch says. “It turns out that T.J.’s wife wouldn’t write to him, so Charlie got Short to write him and send him the photo.“

Short was working as a waitress in Massachusetts when she received the news of the crash. Gordon’s death sent her spiraling into a deep depression. She drifted around the country during the next year-and-a-half until her death, never held another job, and often stayed briefly with friends and acquaintances. In the summer of 1946, she landed in Long Beach in an attempt to resume a romance with another pilot, Gordon Fickling, who she had met at the beginning of the war. “Everyone wants this to be a noir morality play,” Harnisch says. “The aspiring young actress comes to tinsel town with stars in her eyes and this is what happens to impressionable young women who want to be in the movies. The truth is she came out to Southern California for a man. That’s a lot less glamorous.”

Short family photographs, LAPD files.

Short family photographs, LAPD files.

Harnisch interviewed Fickling but is reluctant to share exactly what he said because so many people have plagiarized his blog and he wants to hold some things back for his book. Fickling and Short spent some time in a hotel in Hollywood, but the romance fizzled. She later wrote to him: “Perhaps Matt was my man. That is why I’ve been so miserable.” He returned to Long Beach, and she spent the next few months crashing at the apartments of acquaintances, telling guys she met sob stories – she was having trouble cashing checks or she was a war widow whose baby had died – in order to cadge money for meals. In December 1946, she ended up in San Diego where she met the cashier at an all-night movie theater. When the woman learned that Short was homeless, she invited her to stay at the apartment she shared with her mother and younger brother. Short spent about a month at the apartment, briefly dating a number of men before she met a pipe clamp salesman by the name of Robert “Red” Manley. They dated for about a week and then she joined him on a sales trip as he headed up to L.A. They spent one night at a motel, but it was an “erotically uneventful night,” a reporter wrote.

Writers have portrayed Short as a promiscuous loser sleeping her way across Hollywood. The truth is, Harnisch says, she was just a young woman traumatized by the death of her fiancée, a lost soul — homeless, grieving, and adrift. Harnisch interviewed Short’s youngest sister, Muriel, who told him she has avoided reading anything about the murder, although her daughters had read a few books “because after all she was their aunt…but my poor mother. There was nothing then in the way of support groups…The family has put so much time into trying to get away from it…trying to put it behind us.”

On January 9, Short made up a story about meeting her sister at the Biltmore, so Manley dropped her there. Harnisch figures she was just trying to get rid of him. Manley was the leading suspect at one time, and Harnisch interviewed a detective who investigated him. He also met with a retired LAPD captain who gave him access to material that had belonged to the head of the Homicide Division at the time of Short’s murder, and obtained the recorded interviews of two Dahlia detectives, neither of which has ever been made public. Harnisch disagrees with the claim made by some writers that the detectives were inept, and the case was compromised by department corruption.

“This was a state-of-the-art investigation at the time. They threw hundreds of cops and investigators borrowed from other departments at this murder. Homicide was the elite LAPD unit and Harry Hansen and his partner were experienced professionals. There was zero corruption in this unit. Yes, there was some corruption in the department, but that was mostly in Vice. But covering up a murder corruption—definitely not.”

The Biltmore, with its Spanish and Italian Renaissance design, Moorish beamed ceilings, lavish frescoes and murals, was the city’s most elegant hotel when Short wandered inside. Harnisch strides through the hotel, built in 1923, and stops at the bar, which serves a cocktail known as the Black Dahlia, made with citrus vodka, Kahlua, and Chambord. Harnisch points out that Short did not drink and the Gallery Bar didn’t exist when she arrived at the hotel.

After her body was found in the South Los Angeles lot, a savannah of-ankle high weeds and yard clippings, the afternoon Herald-Express immediately dubbed the killing the Werewolf Murder, but soon found a more evocative name. Reporters discovered the moniker that made her famous when they learned she used to frequent a drugstore in Long Beach. Customers called her the Black Dahlia, a play on the 1946 movie The Blue Dahlia, and because of her swirling black hair and black clothing.

Harnisch is now researching 1946 Long Beach, trying to create a sense of place he can recreate in his book, and searching old newspaper articles, attempting to discover who spent time at the drug store soda fountain where Short hung out and what they knew about her. “I found out that a woman in the drugstore is the one who named her. She said to a cop who also spent time there, ‘They should call her the Black Dahlia.’ The cop is the one who gave this account to the newspapers. All the articles just say he was a cop. But they don’t take the next step. I got his name and his account. And he wasn’t just a cop with the Long Beach P.D. He was a vice cop. That’s why he was so interested in talking to her. They weren’t just chit-chatting. He was checking her out. Multiply getting details like that with a thousand other details and you’ll see why it’s taking me so long to finish the book.”

Researching the case and portraying it accurately has been so difficult because, Harnisch says, Elizabeth Short was the first to fictionalize her life. When she lived in Hollywood for five months, a roommate was an aspiring actress and Short appropriated her tales of casting calls and studio gossip. She wrote her mother and told friends she was pursuing an acting career, yet she never took an acting class or showed any interest in the movies. She claimed that she worked as a waitress while living in L.A, yet she never held a job here. She claimed to be a war widow, yet she never married her fiancée. She claimed her infant son had died, yet she never had a child. She concocted numerous other sob stories to con men she had briefly met out of a few bucks. What Harnisch does know is that after her fiancé was killed, her life careened out of control, dissipating her ambition and her rectitude. Researching Walter Bayley has been equally difficult for Harnisch. At times, he felt as if he was chasing a shadow. Trying to accurately chronicle the boyhood, career, war experiences, mental decline, flaws and foibles, and the marriage and eventual dissolution of the union of an unremarkable man born in 1880 seemed, at times, like a quixotic quest. Finally, the murder has been the most frustrating pursuit of all. After spending more than two decades investigating the case and Los Angeles history, and researching the victim and a suspect, Harnisch anticipates finally finishing his book next year.

“This is not a story where the victim got justice, the family got closure, and the killer was captured and punished,” he says. “As a result, this is a story that fades to conjecture. This is a story without an ending.”

—Featured illustration by Eleonore Hamelin, courtesy The Delacorte Review