The just-released books that you’re reading now were likely written during Covid lockdown, a period that was weird for authors—this author at least—in the sense that, it wasn’t that weird at all.

In those early lockdown days, my social media feed was, in the most part, a narration of other people’s strange new routines: working from home, staying in pajamas, eating leftovers for lunch, seeing no one. It seemed churlish to hit all caps and respond, YOU DO KNOW THIS IS HOW WRITER’S EXIST ALL THE TIME, RIGHT? Especially churlish when, for one beautiful moment, social media was a nice place to be.

The news was dire, yet this window on the world was rose-tinted. Parents were building epic Lego-scapes with their children, others stitched, most of us baked. Neighbors who had never spoken before were forging bonds and performing symphonies, both literal and metaphorical. Whole symphonies of generosity scrolled across my laptop screen! Which was great news for humanity; a total nightmare for a thriller writer.

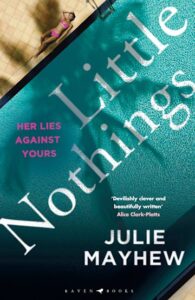

I wrote the first draft of Little Nothings in those first months of isolation—a book led by Liv Travers, a woman with a solitary personality (so far so Covid-friendly) who, after giving birth to a daughter, forms strong bonds with fellow mothers Beth and Binnie. Then along comes Ange—an aspirational new member to their group and a divisive one. On a joint holiday-of-a-lifetime to Corfu, Liv discovers just how narcissistically divisive Ange can be. Duped, then dumped, Liv plots her merciless revenge.

Except she sort of doesn’t. Not really. Not in that first draft.

With a deadly virus tearing through the population, with livelihoods dwindling and small businesses collapsing, and with social media beaconing the message that we must in the face of this be stoic, jolly and above all kind, I couldn’t follow through on my promise to write a book about betrayal, bitterness and wrath. As a kindness, I held back.

I should have been writing a comedy, that’s what I told myself, or else a romance; a happy ever after was what people needed right now. If darkness must feature, then let my story speak to the real-life drama unfolding around us. No plot conjured up in an author’s mind could rival the suspense and horror of the pandemic. It was ridiculous to be playing make believe instead of addressing the immediate truth.

In the end, the truth came to me. I lost my mum to Covid.

My novel draft sat untouched. Not because I didn’t want to write—writing had always been my lifelong way of dealing with everything, no matter how terrible. I stopped work because I was convinced that grief had made me mad and that any words I set down on the page could not be trusted. I asked my publisher to wait.

In the meantime, I read lots, and watched even more, filling my brain with stories that offered escape from my own. By the time Covid dramas started hitting our TV screens (written by peers who had not ignored that call from the pandemic muse) I was ready to see them, eager for connection, for the catharsis of seeing my own experience and emotions being portrayed by others.

But that’s not what I got. I sat through a drama that left me cold, then raging—a drama that didn’t come anywhere close to showing the squalid reality of losing a loved one to the virus, no chance to say goodbye. Maybe it was moving enough to draw tears and plaudits from the uninitiated but for me, it pulled punches. It Disneyfied my experience. And this did not feel like a kindness; it was an insult.

When I eventually returned to my desk, my social media feed was filled with finger-pointing, a daily accounting of our Covid villains, driven by the human desire for people to be wholly good or bad—an environment far more conducive to the thriller writer. My agent’s response to my first, gentle draft of Little Nothings leapt out with fresh meaning, ‘I thought you were really going to go there at the end,’ she said, ‘and I felt let down when you didn’t.’

Though we turn to fiction for escape, there is no requirement that these holidays of the mind be sunny. In crime and thriller, the setting can be warm and exotic, but the characters are likely shady, unsympathetic, violent. And it is this propensity for violence which often provokes criticism from those not so enthralled with the genre. The action is too unpleasant, they say, too gruesome. Fans of these books get called voyeurs.

But it is reductive to cast readers as passive observers, to suggest that their decision to spend hours, days or weeks consuming one story rather than another is basely simple, not nuanced, involved. We go to a book seeking something, and though we are not always conscious of the needs we’re feeding, we are definitely awake to the fact of whether they have been satisfied by the final page.

So, a classic police procedural done well will gift us a sense of order and justice in a chaotic world. A domestic thriller provides reassurance that our own relationships are solid (or else it prods us towards the path of change). Supernatural stories turn the fears that haunt our internal lives into ‘real’ ghosts that we might confront, then exorcise.

And to achieve this satisfying result—this wonderful catharsis—an author cannot play nice, nor pull their punches. They must ‘really go there’—show the reader how bad things are, or were, or can be. Because without this initial acknowledgment of the awfulness of a situation, the journey to redemption and resolution means nothing, a reader feels nothing, only a sense of grievance towards the writer.

At its heart, Little Nothings operates as a revenge fantasy. I had experienced what Liv had—the shame of being dumped by a group of friends. I’d read articles by women describing the unique pain of being excluded, and I had spoken to mothers who were guiding their daughters through their first taste of the toxicity that can grow unchecked within female groups.

For my book to work, Liv had to experience the worst of this, then have her rage be given free reign. Following characters who are willing to do the terrible things that we would never dare to is another truly cathartic offering of the thriller. Within the boundaries of fiction readers can scratch dark itches, understand the perils of inhabiting their shadow selves, before returning to enviably quieter lives, safe in the knowledge that no one got hurt.

To compensate for my tentative start on Little Nothings I wrote a truly brutal second draft, arriving in the end at a final version that sat somewhere between those two takes, evidence perhaps that ‘really going there’ doesn’t mean pushing your characters and plot to unbelievable extremes. The simple ask is not to shy from the material nor emotional truth of a subject, to trust that a reader is willing to travel to hell, just as long as you promise to bring them back again feeling in some way lighter, freer, purged. That journey is exactly what they’ve signed up for. And in offering it to them, there is a kindness.

***

Julie Mayhew’s novel Little Nothings is published by Bloomsbury.