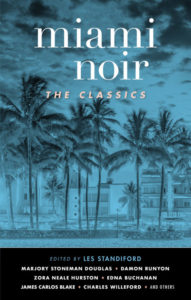

When I wrote the introduction to the original Miami Noir in 2007, I spoke of the relative youth of the city, barely more than one century and one decade old at the time, and of the appropriate fact of the irascible crime story as its reigning literary emblem. There might come a day, I theorized, when Miami—having acquired its art and science museums, and its thriving opera house and shimmering performing arts centers—would have developed the ease and the multifaceted cultural and historical backdrop from which reserved and careful works exhibiting the decorum of literature some purists denote with a capital “L” might be spawned.

But, said I, Miami remained at the time essentially a frontier town, a city on the edge of the continent, inviting all comers, full of fractious delight, where nothing of import had been settled, where no special interest group could yet claim control of politics or culture, and every day brought a new melee between some subset of those on the make and destined for collision. The perfect literary medium to give voice to such a place, I ventured, was the story of crime and punishment.

As I write today, despite the fact that Miami has in the past decade-plus added a downtown performing arts complex to outdo all but the Kennedy Center in DC, a jaw-dropping art museum by the Biscayne Bay, an exemplary science museum, the establishment of the world-renowned Art Basel festival on Miami Beach, and so much more, I am sticking to my metaphorical guns: the operative literary form to portray Miami—the essential aria of the Magic City—is spun from threads of mystery and yearning and darkness.

The lure of Miami remains to this day essentially what it was when Ponce de León and his men crossed the Atlantic in search of streets paved with gold and glistening with waters that spilled over from a fountain of youth. By the thousands, each year, they still come—immigrants, retirees, high rollers, jokers and midnight tokers, by yacht, by raft, by RV, by thumb—all in search of one or another version of the same impossible promise. Who would expect a series of drawing room comedies to emerge from such a scene?

And here is one more consideration: when terrible things threaten in some ominous neighborhoods, in some tough cities, a reader of a story set in those locales might be forgiven for expecting the worst; but when calamity takes place against the backdrop of paradise, as we have here in Miami, the impact is all the greater.

And yet with all that said, when Johnny Temple from Akashic Books first proposed a second volume of Miami Noir, I was doubtful. The sequel was to be subtitled “The Classics,” Johnny explained. Unlike the first collection, which invited original stories from a set of working Miami writers, this was to be a collection of previously published stories in the genre, one to give a sense of how the story of crime and punishment had developed along with the history of the place.

“But we don’t have a history,” I protested to Johnny. “At least not one that includes much story publishing, let alone noir publishing.”

“I don’t believe it,” was the essence of Johnny’s response. “Go to work and get back to me when you’ve got something.”

Though I thought there was about as much possibility as me coming up with a volume of Des Moines Noir, I took Johnny at his word and began the search. Having penned a series of crime thrillers of my own featuring the travails of honest (!) Miami building contractor John Deal, I was familiar with the work of the so-called “Miami School” of crime writers who came to attention in the eighties and nineties, including Charles Willeford, Elmore Leonard, Carl Hiaasen, James W. Hall, James Grippando, Barbara Parker, and so many others. But most of us were writing novels, the paying markets for short crime and mystery fiction having shrunk to relatively nothing by the time.

Furthermore, prior to that great flowering that came with such titles as Miami Blues and Stick and Strip Tease, Miami was simply not much of a writer’s town, let alone a mystery writer’s town. John D. MacDonald had of course immortalized fictional South Florida detective Travis McGee in a series of twenty-one novels published from 1964 to 1985, but McGee operated out of his houseboat The Busted Flush, docked thirty miles up the road at the Bahia Mar marina in Fort Lauderdale, and while MacDonald produced a few short stories set in various South Florida locations, none were set in Miami.

I by chance learned of the work of Douglas Fairbairn back in the early 1980s shortly after I arrived in Miami, when his niece, playwright Susan Westfall, put me onto his matchless thriller, Street 8, which tells the story of used-car dealer Bobby Mead and his ill-fated run-in with a group of Cuban expatriates looking for a warehouse in which to store munitions destined for a Bay of Pigs–styled invasion. I found the book astonishing—in my view the very prototype of nearly all the best Miami crime novels that have followed—and even though Fairbairn, who fell victim to early onset dementia, never wrote another piece of Miami-based fiction, much of Street 8 (Fairbairn’s original title was Calle Ocho but his publishers complained that English-speaking readers would be puzzled and leaned on the author to come up with an alternate title) is told episodically, enabling me to convince Johnny to include an excerpt of this very important work.

In fact, it was that decision which came to form the philosophical cornerstone for this collection, something of the opposite of the original intention. Here is what I mean: while there may be something of an overview of the development of the Miami crime story over the past century to be found in these pages, I think there is a much greater cogency to be found in the overview of the history of a most unusual and distinctive place reflected here. Furthermore, that sense of history is delivered with none of the typically dusty overtones of an all-too-often dry and arcane subject, given that at the forefront of nearly all the tales are questions of life or death.

The Fairbairn material would be the perfect linchpin between the past and the contemporary crime writers, I reasoned, as I set out in earnest on my search for what had come before. I could only hope that there were short stories to be found to illustrate the point.

As I detailed in the introduction to the original Miami Noir, there have been a number of early crime novels set in Miami, including Kid Galahad (1936) by Francis Wallace, about mob-influenced boxing; Leslie Charteris’s The Saint in Miami (1940), an installment in the British series; and several Brett Halliday–penned Mike Shayne novels of the forties and fifties, with Shayne operating as pretty much the lone capable moral force in a tropical landscape long on beauty but short on rectitude.

The Brett Halliday moniker was in fact only one pen name employed by Davis Dresser, who (while spending much of his time in Santa Barbara) wrote dozens of novels of all stripes, but, as it turns out, nary a single short story to be found set in Miami, with the exception of the bordering-on-novella-length piece included in this volume, “A Taste for Cognac,” originally published in Black Mask magazine in 1944. In fact, the story was later published as a stand-alone “dime novel” in 1951 and bundled with another story/novella, “Dead Man’s Diary,” as a kind of omnibus in 1959. While it may test the limit of what can be termed a “short” story, the piece is not only relatively compact, it contains the usual tropes and carries the blunt force typical of a Shayne novel.

Another author high on the wish list was the master of the wise guy form, Damon Runyon. While much of Runyon’s short story work was of course set in New York, he was a widely traveled reporter and correspondent not averse to the occasional Florida trip to inspect how the ponies might be running during the winter and to escape the snowdrifts for a bit. “A Job for the Macarone,” published originally in a 1937 issue of the Saturday Evening Post, is proof of the latter and perhaps the only Miami-based story to be penned by Runyon.

Lester Dent may be best remembered today as the creator of the long-running Doc Savage series, but in the mid-1930s, as that phenomenon was gathering steam, Dent was exploring other possibilities, including a series based around the exploits of a Miami-based detective named Oscar Sail living aboard a schooner anchored in Biscayne Bay. That series never came to fruition, but tantalizing hints of what it might have become are found in two stories published by Dent in Black Mask magazine. “Luck,” included here, was Dent’s original version of the story finally published in 1936 as “Sail,” the latter somewhat diminished by changes demanded of the author by the magazine’s editors. There are some who contend that Oscar Sail came to live on as the prototype for that other live-aboard private investigator just up A1A a few miles, but if John D. MacDonald found Oscar Sail a viable model for Travis McGee, he never said so.

A somewhat anomalous addition to this volume is the segment from the later pages of Their Eyes Were Watching God, the tough-about-the-edges novel published by Zora Neale Hurston in 1937. While an excerpt, it is nonetheless a self-contained one, detailing the dark and tragic end of narrator Janie’s third marriage in the aftermath of a powerful hurricane that sweeps through the Everglades, one very likely modeled after the real-life monster storm of 1928. Given the vivid detailing of an often-overlooked segment of South Florida’s population, the theme-appropriate nature of the book’s climax, and the ever-growing critical stature and influence that Ms. Hurston’s work has gained over the past half century, it seemed to this writer a crime not to include the passage.

The earliest publication in the volume—and perhaps the first piece of Miami crime fiction to be published—comes from the pen of a writer seldom associated with the genre: Marjory Stoneman Douglas, more commonly lionized by conservationists for her classic 1947 work of nonfiction, The Everglades: River of Grass, a book generally given credit for the eventual establishment of Everglades National Park. From 1915 to 1923, however, she was a hardworking reporter for the Miami Herald, which her father had helped establish, and she was also submitting poetry, plays, and fiction to outlets across the country. One of her first big scores was White Midnight, a novella about sunken treasure in the West Indies, for which Black Mask paid her six hundred dollars in 1924. “Pineland,” included here, was originally published by the Saturday Evening Post in August of 1925 and, along with the work of Zora Neale Hurston, provides ample evidence that tough, capable women have populated South Florida for a good long time.

There were a few other short stories from the pre-Fairbairn years that surfaced, but not many, and none, in the opinion of this writer, with a great deal to recommend them. In fact, the efforts of Douglas, Dent, Hurston, Runyon, and Halliday exhibit collectively the archetypal trove for just about everything that has appeared in the genre ever after, including literary excellence.

And while it has seemed to me to be appropriate and even necessary to lend a few words of context to those works penned by those who are no longer with us, I am not so sure I want to put myself in the position of interloper between readers and the still-working colleagues collected here. Better to let the work of these fine and able practitioners do the talking, with the only presumption of the editor being this: I would not have included any of these works if I did not find them captivating, well-wrought, and in one way or another, exemplary.

Which of course leads me to a few last words, given that two of the modern masters included have in fact passed on. It seems impossible that Charles Willeford has been gone for more than thirty years, for the legacy of his work continues to burn bright for all of us in the field and for anyone who has read it. Many in fact refer to Willeford as the godfather of the Miami School, and his in-your-face approach continues to inspire young writers who might have been a bit too cautious before reading Sideswipe or Kiss Your Ass Goodbye. Charles once proudly showed me a copy of one of his novels, sent back to him by a fan, accompanied by a terse note: Just thought you’d like to see what I thought of your new book, it said. The book had been punctured dead center by what must have been a .45 slug, shards of its innards blown out and curled against the back cover in perfect symmetry. He thought it one of the funniest things he’d ever seen.

There were a number of Willeford stories to choose from, but I thought it would be a disservice to an old pal if I were to pick something that lacked an outrageous component. As a promotional line for a film adaptation of the Terry Southern novel Candy once stated: “This movie has something in it to offend almost anyone.” So, included in this volume is “Saturday Night Special.” I’ll add only this: Willeford did not write in order to present models of decent behavior. He simply saw us for what we truly are, and he wrote accordingly.

The last I’ll single out is Elmore Leonard, sometimes referred to as the Dickens of Detroit—but “Dutch,” as he was known to his friends, was also the Maestro of the Miami Academy of Crime. Leonard could effortlessly propel a story almost entirely via dialogue, yet there was never any mistaking that the fuel for his characters’ repartee came from the streets where they lived, whether they be those of the Motor City or of South Beach. And like Willeford, humor played a large part in most of the darkest of Leonard’s Miami proceedings, though in Willeford’s case the guffaws grew out of the macabre, while the humor in the latter’s was more of the eye-rolling type derived from Runyon. The sole Miami-based short story penned by Leonard was not available for this volume, but included here is his chapter created for the peerless pass-along novel of Miami, Naked Came the Manatee, where each author did her or his best to keep a steadily compounding tale going, adding an episode to whatever stage the yarn was at when it landed on the desk. In fact, Leonard’s so-called chapter “The Odyssey,” included here, strikes this writer as a fully self-contained piece that Leonard had already on hand when the invitation to participate in Naked Came the Manatee arrived.

All the above, then, will have to serve as the companion notes for the enjoyment of this volume, though I might offer one final observation. Some of the older stories contain language that, though used as part of the popular parlance of the time, are frankly racist and deeply offensive today. A character in the Douglas story refers to nigras working and living as field hands in close proximity to her home, and in the Dent story there is an offhand reference to a darkie working as a service person in a restaurant. Even the Hurston excerpt uses phonetic reproduction of dialect spoken by the characters that might raise an eyebrow. Yet it has been the editorial decision for this volume to reproduce the stories exactly as they were originally published. This does not constitute endorsement of any failings of an earlier time in history, by any means, but it does permit the contemporary reader the opportunity to consider the shortcomings of another era, and allows for each reader to make independent judgments as to the impact of such upon the whole and upon the continuing value of the works at hand.

Go ye forward, then.

Les Standiford

Miami, Florida

August 2020

___________________________________

Excerpted from Miami Noir: The Classics, edited by Les Standiford, copyright 2020 by Les Standiford, used with permission of the author and Akashic Books (akashicbooks.com).