As adoring crowds look on in horror, a popular president is struck by two bullets from a weapon wielded by a lone gunman during a goodwill visit to a newly thriving American city. In the wake of the shooting, law enforcement officials and most of the public are convinced that the man who fired the shots had not acted alone, but that he is simply the tip of a conspiracy initiated by a revolutionary fringe group dedicated to the overthrow of democracy in the United States. Although the gunman is quickly apprehended, he refuses to discuss the incident. Despite vigorous investigation, not even the flimsiest evidence can be found linking any of the radicals to the crime. Although many remain convinced that a wider plot had been afoot, they are forced to reluctantly accept that the conspirators will never answer for their misdeeds.

But then, dark rumors begin to circulate, mostly in whispers, that there may have indeed been a plot to murder the president, but that its origins had been more ominous, that the conspirators had been working from inside the government, and that the killer had merely been a dupe. But here too, although certain damning facts cannot be explained away, sufficient proof to make an accusation is not to be found. Soon afterward, the assassin is dead, with whatever knowledge he might have possessed carried with him to the grave. And so, this most heinous of all crimes passes into history with many questions unanswered, no clear explanation of the facts, and no proof that justice had fully been done.

The shadowy gunman who may or may not have been acting alone is not Lee Harvey Oswald, but rather Leon Czolgosz, and the president is not John F. Kennedy, but William McKinley.

***

It was just after 4 p.m., September 6, 1901, after a speech in the Temple of Music at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, and President McKinley wanted personally to greet the public.

“The Pan” was the largest, most expensive event of its kind ever mounted in an outlying American city. Set on 432 acres and boasting over 150 buildings, the fair contained a dazzling variety of exhibitions and pavilions, from the mundane to the exotic: the Acetlylene Building; Beautiful Orient; Nebraska Sod House; House Upside Down; Trip to the Moon; Philippine Village; Miniature Railroad; and Infant Incubator. Exhibits were devoted to horticulture, forestry, mining, dairy farming, graphic arts, women, and Indians.

In the center of the midway rose a 410-foot, forty-stories-tall Tower of Electricity, officially dubbed Propylaea, with elevators available, for a fee, to take visitors to the top, where, on a clear day, Niagara Falls was plainly visible. Powered through the hydroelectric facility at the Falls to the north, Propylaea was lit every night in a brilliant display visible across the border to what was hoped to be a suitably awed Canada.

The Temple of Music was the Pan’s largest building, fifty yards square, with cylindrical, domed appendages truncating each corner. Predominantly red, with gold and yellow trim, and panels in blue and green, the structure was topped with a dome almost two hundred feet high and festooned with ornate sculptures paying homage to the Great God Music. Inside was seating for two thousand.

Security for the president was tight, certainly by the standards of the day. As both John Wilkes Booth and Charles Guiteau, the man who assassinated President Garfield, had fired from extremely close range, emphasis was on securing the immediate area. Well wishers were forced into a single line, two Secret Service agents, George Foster and Sam Ireland, flanked McKinley, and a special contingent of United States Army and Buffalo police was stationed throughout the venue.

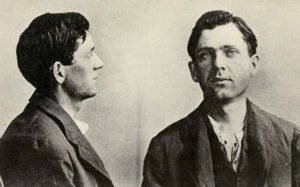

Leon Czolgosz, September 7, 1901, in custody the day after he shot McKinley.

Leon Czolgosz, September 7, 1901, in custody the day after he shot McKinley.

Still, Leon Czolgosz, a slight twenty-eight year old with an outsized bandage wrapped around his left hand, got off two shots at point blank range with an Iver Johnson .32 caliber safety automatic revolver that he had hidden under the wrapping. The first bullet struck the president’s breastbone but didn’t penetrate; McKinley apparently later picked it out of his chest himself. The second, however, perforated the president’s abdomen. The assassin was wrestled to the ground by “Big Jim” Parker, an African-American who was standing just behind Czolgosz on the receiving line. Czolgosz, beaten and bloodied, was hauled off to jail, saying only, “I done my duty.” He was almost immediately identified as an anarchist, a worldwide movement that had already been responsible for a number of assassinations in Europe.

Within forty-eight hours, anarchist leaders were arrested in a number of American cities, most in Chicago, where Czolgosz had visited. Despite intense police grilling, although they admitted meeting Czologsz breifly, they denied all knowledge of the crime. In fact, one of the anarchists, Abe Isaak, published a warning in his newspaper, Free Society, that Czolgosz was likely a police agent. A warrant was also issued for Emma Goldman, the “high priestess of anarchy,” but she wasn’t found until days later. She claimed it would have been idiocy for her to put up a fool like Czolgosz to commit such an act. Eventually, Isaak, Goldman, and the rest were released, and despite pronouncements by the police that the investigation was ongoing, they were never re-arrested.

McKinley was rushed by electric ambulance to the fair’s Emergency Hospital. A gynecologist who had been on the premises exhibiting flowers saw to the president’s wounds and stitched him up. The second bullet, specialists agreed, was lodged in a muscle in his back and was safer left in to avoid the risk of delicate abdominal surgery.

The McKinley assassination was irresistible because so many questions were never adequately answered.

At first, it seemed as if the president would make a full recovery. For a week, he improved steadily, to the point where he was given solid food, and even asked for a cigar. But the bullet was not in McKinley’s back. The wound festered and caused gangrene in the lining of his stomach, and the day after he was given eggs and toast, he became critically ill. Within a day after that, he was dead.

It was only then that some began to ask how Czolgosz was able to get so close to McKinley with two veteran Secret Service operatives standing right there, charged with preventing just that sort of crime. Foster and Ireland claimed to have been distracted, but there were no distractions present. And why was it Big Jim Parker—who, at 6’ 6”, really was big—who tackled the assassin, preventing him from getting off a third shot? There were even those who wondered how distraught Vice President Theodore Roosevelt really was, since the only thing he and McKinley shared was a deep dislike for one another.

And then there was the money, tens of millions of dollars.

***

I’m always on the lookout for an incident where the history can be absolutely accurate and still yield a plot that is both plausible and engrossing. The McKinley assassination was irresistible because so many questions were never adequately answered. One of the reasons I’m drawn to fiction is that I get to explore some theories for which there is not sufficient evidence to do as straight history.

I was also fascinated to write about the anarchists, because the issues that drove them are becoming more and more manifest today. We, as they, live in a period of enormous technological change, major societal disruption, large movements of people from one region or country to another, and the amassing of great wealth by a few. This leads many to insist that the basic institutions of government be altered to accommodate those changes by creating a greater range of opportunity and care for those most at risk, and others to fight ferociously to maintain institutions as they are, or in some cases were. The clashes that inevitably spring from this hardening of points of view must be either resolved to everyone’s satisfaction in part but no one’s satisfaction in full, or society can descend into a cycle of hatred and violence. That was the risk then, and I think it is the risk now. While in writing a mystery, I can never let politics get in the way of the story, incorporating social issues can add a dimension and make the narrative that much more compelling.

***