There are few people who know I write poetry as my work is rarely shared and to date none of my poems have ever been published. My work as a crime novelist leaves me completely exposed to critique on multiple platforms, a situation which is tolerable only because I rarely take the criticism personally. A reviewer may attack the quality of my writing, but never me as an individual. Contrary to what some readers may believe, my novels are not autobiographical. I save my personal life for my poems, which means there is nowhere to hide once they are out there in the world. It is therefore not without serious reservations that I am including a couple of my poems in this piece.

Most of my poetry attempts to make sense of some recent emotional upheaval or revisits unresolved incidents from my childhood, but I also use poetry to inform and improve the imagery in my prose, a useful exercise that I started employing when I was writing my first novel. I’ve recently taken this process one step further by studying published works of poetry as I attempt to find new voices for my characters.

I’ve chosen to write my latest novel, a psychological thriller set in London, using first person as the point of view. My narrator, Jessica, is a recovering alcoholic who was forced to relinquish all parental rights after her actions put her seven-year-old daughter’s life at risk. Sixteen years have passed and she is back in London hoping for a second chance. Whether she and her daughter will survive the reunion is anyone’s guess. Jessica is a woman whose life experiences are far removed from my own. If I was going to write from her point of view successfully I was going to have find new ways to explore her troubled mind. I’ve drawn much needed inspiration from Anne Sexton’s poetry. Sexton was known for writing highly confessional poems that touched on everything from her issues with mental health to her desire to take her own life.

My poetry is deeply personal, but as the writing often contains Escheresque phrasing and few concrete images; the reader is kept at a safe distance. The poems tend to be short and while the clues are all there in the text, their true meaning is never presented in an obvious manner. More often than not they deal with the emotional distress and loneliness resulting from broken relationships. The following poem, “Through Doors That Close,” explores the isolation I felt even when I was in a relationship.

Through Doors That Close

All skin and no bones,

I wander your home,

Down stairs that rise,

Through doors that close.

I pad past your past,

Cold-footed on gritty tiles,

Under ceilings that let in skies,

To a room where no one cooks.

Here’s the water,

Here’s the wine,

Here’s the tea.

I sit. You serve.

I sip. You smile.

Outside your gate

The ground gives way.

I fall. You rise.

The poems about my childhood are a certainly a form of memoir, but without the weight of detail they become almost universal in their tonality. I’m conjuring up childhood memories that can’t help but be diluted by distance and time. The result is nostalgic, but rarely sentimental. As is the case with a majority of my written work—social isolation, loss, and the threat of violence are never far away.

Indian River, 1972

It must have been a weekend.

We’re off school and our parents

have been drinking since lunch.

The motorboats are secured on long lines

that stretch tight to the shore.

The boats rock in the waves.

I get dizzy if I stare too long.

The island is all scrubby pine

and bits of debris.

And hot as fuck.

We’d been playing hide and seek,

but the younger ones are starting to whine.

I find a dead horseshoe crab

and flip it on its back.

Flies swarm and a stink fills the air.

A girl says it’s gross.

On the beach the grown ups are digging

in the shallows with shovels.

A burlap sack is nearly full

of clams the size of a men’s fists.

My daddy says I have to be patient

if I want to help catch them.

He points to the wet sand

and tells me to watch for bubbles

They gotta breathe sometime, he says.

That’s when we dig.

I also write poetry for purely utilitarian reasons as I find it helpful to approach highly emotive scenes in my novels first as poetry. It is basically free writing, but in verse. In the absence of the usual constraints there’s an increased chance of stumbling upon unique ways to describe the natural world and human emotions. Unusual word juxtapositions also emerge, an example being bone dust white, a phrase used to describe a child’s breath on a frigid winter morning, which incidentally became the title of my first novel. When I’m free writing poetry it often feels like I’m taking down dictation from an unseen source. Ideas tend to emerge in surprising ways. After I’m finished I get out my highlighter and mine the unedited poems for interesting imagery and phrasing. The poems are then abandoned to the piles of notebooks thrown beneath my writing desk. Though their purpose is fleeting, I never have the heart to throw these poems away.

Writing a novel in first person has thrown up some interesting challenges. I normally write in a fairly cinematic manner, sitting at my character’s shoulder as I take a close third person point of view. As the scene plays out, I am in the position to see everything that happens. Writing in first person is constrained in comparison. I’ve suddenly found myself in my novel’s only blind spot. Aside from the occasional glimpse in a mirror, my narrator remains invisible to me. I only see what she sees. My experiences are limited to the history she has amassed, much of which is disturbing. I’m living in the head of a recovering alcoholic who can’t remember the night her actions nearly cost her daughter’s life. It is imperative that I find this woman’s voice. I need to understand her past, her present, her emotional state, her desires, her fears, her confusion, her guilt, her shame, her addictions, her relationships and her quiet desperation if I’m going to take up residence in her head.

I’m fortunate to have a close friend who is both a published poet and taskmaster. When I was going through a recent crisis of confidence with my writing, he advised me to step away from my novels for a short time and write a poem a day, which I would send to him to review. I have serious reservations about over-sharing, which is probably why most of the poems I submitted were inspired by childhood memories. At one point he grew frustrated and asked why I didn’t write more about what was happening to me in the present day. He sent me the following excerpt from “45 Mercy Street” by Anne Sexton and told me that “this is the kind of shit you should be writing” (his words not mine).

45 Mercy Street (excerpt)

I walk in a yellow dress

and a white pocketbook stuffed with cigarettes,

enough pills, my wallet, my keys,

and being twenty-eight, or is it forty-five?

I walk. I walk.

I hold matches at street signs

for it is dark,

as dark as the leathery dead

and I have lost my green Ford,

my house in the suburbs,

two little kids

sucked up like pollen by the bee in me

and a husband

who has wiped off his eyes

in order not to see my inside out

and I am walking and looking

and this is no dream

just my oily life

where the people are alibis

and the street is unfindable for an

entire lifetime.

I read “45 Mercy Street” in its entirety a dozen times before going on to read a lot more of Sexton’s poetry. My friend’s failed attempt to turn me into a poet had inadvertently introduced me to a unique way of tapping into my narrator’s troubled mind. Sexton was the voice of desperation I’d been looking for. I’ve since returned to my novel with a renewed sense of energy.

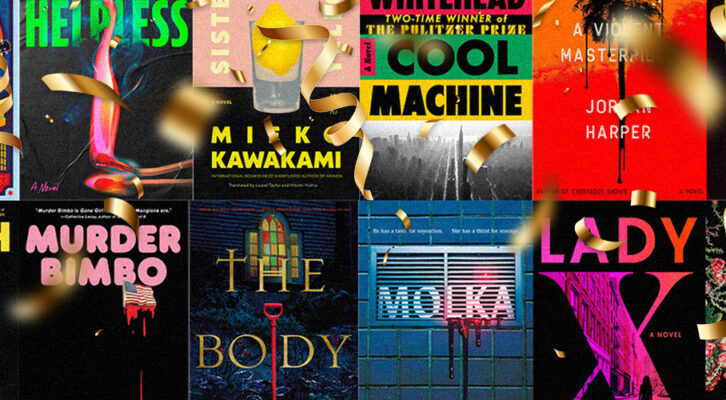

Prose and poetry represent two interchangeable sides to my personality. One keeps me sane and the other helps me make sense of my insanity. One is my public face and the other is my private. One taps into my deepest secrets and the other benefits from the long exhalation that comes from writing without boundaries. I’ve recently come to the realization that I cannot have one without the other. Prescribed or otherwise, I will continue writing poetry. Someday I may even go full Sexton and put together my own collection of confessional poetry. Until then the notebooks will continue to gather beneath my feet as I write novels about troubled women who are just aching to find their voice.