The Emmanuel Baptist Church of Capp Street was cursed from the start. In 1878, the church moved from a rented hall on 22nd and Folsom to more permanent digs at 22nd and Capp. A short time later, the church’s first pastor, Reverend Charles Hughes, slashed his own throat with a straight razor. His replacement chose a more common method of suicide and shot himself in the head. Two ministers. Two suicides. You’d think that Mission residents would’ve burned the place to the ground after that and called it a day, but the church kept going.

The third pastor, Isaac Milton “I.M.” Kalloch, was young and politically connected. His father, Isaac Smith “I.S.” Kalloch, a minister himself was a higher-up in the powerful Workingmen’s Party, which had won almost every seat on the Board of Supervisors on the strength of its really ugly anti-Chinese campaign. Rampant racism made the elder Kalloch a favorite to win the mayoral race of 1879.

But Charles and Michael de Young backed another candidate and started slinging the mud in the Chron’s editorial pages. In August 1879, the Chron ran a story “severely animadverting upon the character and moral standing” of I.S. Kalloch’s dead father. It was on. Kalloch responded by calling the de Youngs “bastard progeny, born in the slums and nursed in the lap of a prostitute” during a speech at the Metropolitan Hotel.

Now this whole de Young “Mama was a whore” rumor came from an 1874 story in the competing San Francisco Sun. After the Sun ran the rumor, Charles de Young shot it out with the Sun’s editor on Market Street. The newspapermen managed to miss each other, but a young boy was shot in the leg. The Chronicle sent the kid $100 and nobody went to prison. Five years later, Kalloch not only read from the story but threatened to reprint it in the Workingmen’s Party newsletter.

On August 23, 1879, Charles de Young went by carriage to the Metropolitan Church where Kalloch was addressing a gathering. He sent a messenger to get Kalloch. When Kalloch emerged from the church, de Young put one shot in his chest and another in his hip, making this a Victorian era drive-by. As de Young tried to escape, a crowd of people overturned his carriage and pulled him out. “He was dreadfully kicked and bruised,” according to a wire story. De Young got himself arrested just to survive. The Chronicle had to station armed guards around its offices to keep mobs from trashing the place.

“The city is intensely excited,” the Deseret News of Salt Lake City reported. “There was never a time when San Francisco was more angry.”

Kalloch survived the shooting and won the mayoral race. Charles de Young was released on bail and hid out back east until things died down. But when he came back to San Francisco, he published a pamphlet bashing Kalloch all over again. De Young just kept at it. Until I.M. Kalloch, the son and pastor of the cursed church, stormed the Chron’s offices on April 23, 1880, and shot Charles five times, dead.

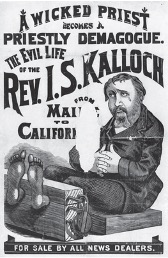

A pamphlet slandering mayoral candidate i.S. Kalloch likely distributed by chronicle publisher charles Deyoung. Image is by courtesy of Hamilton Henry Dobbin Collection at the California State Library.

A pamphlet slandering mayoral candidate i.S. Kalloch likely distributed by chronicle publisher charles Deyoung. Image is by courtesy of Hamilton Henry Dobbin Collection at the California State Library.

I.M. Kalloch was acquitted in March 1881 in a trial where several witnesses were jailed for perjury. Mayor I.S. Kalloch was indicted for taking bribes in 1882, but beat the case and served out his full term. Charles de Young was downplayed if not erased entirely from civic and family histories. His brother Michael took over the paper and became part of a shooting scandal of his own barely three years later. Emmanuel Baptist Church hit a gruesome trifecta with two suicides and a murderer, but even with three deaths in less than three

years, the little church somehow endured.

The congregation moved to a new building on Bartlett Street between 22nd and 23rd in 1890, and things stayed quiet for nearly five years. When the Reverend John George Gibson took over the church in 1894, his predecessor didn’t even have blood on his hands. But the curse came back, and this time it was bloodier than ever.

On Saturday, April 13, 1895, a group of church ladies was decorating the pulpit for the next day’s lavish Easter Sunday celebrations when one of them found the blood-drenched body of a young woman in a small library storeroom.

“The girl had been assaulted and her remains had been cut and hacked,” the Spokesman-Review of Spokane, Washington, later reported. The victim had also “been gagged by the assailant” with “a part of her underclothing” that was jammed down her throat “with a sharp stick.”

At first, the churchwomen thought the body was 21-year-old Blanche Lamont, a popular member of the congregation who had been missing for 10 days. However, the body was later identified as Minnie Williams, a woman who liked the church enough to journey from Alameda by ferry for services. Lamont only stayed missing for another day before a search of the church grounds uncovered her body at the top of a rickety staircase in the church’s ominous bell tower. She was “stripped of her clothing with her hands clasped upon her breast,” according to the Chron. Unlike Williams, Lamont was not mutilated beyond “the marks of fingers that had been pressed deep into the tender flesh” and the damage done by 11 days of decomposition. The cursed church could now add a double homicide to its litany of misfortunes.

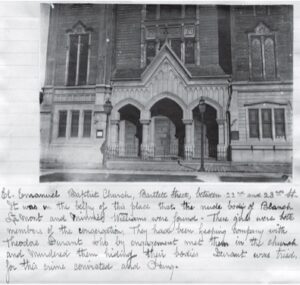

The cursed Emanuel Baptist church on Bartlett Street between 22nd and 23rd Streets where proto serial killer Theodore Durrant brutally murdered Blanche Lamont and Minnie Williams in 1895. Image courtesy of Hamilton Henry Dobbin Collection at the California State Library.

The cursed Emanuel Baptist church on Bartlett Street between 22nd and 23rd Streets where proto serial killer Theodore Durrant brutally murdered Blanche Lamont and Minnie Williams in 1895. Image courtesy of Hamilton Henry Dobbin Collection at the California State Library.

Police quickly arrested W.H.T. “Theodore” Durrant, a medical student and superintendent of Emmanuel Baptist’s Sunday school, who was identified by several eyewitnesses as the last man seen with both victims. Durrant denied killing the two women, but Williams’s purse was found in Durrant’s coat during a search of his house. A pawnbroker later testified that Durrant had tried to sell him one of Lamont’s rings days after her disappearance. Durrant’s two-month trial moved a lot of newsprint as the Chron and Examiner used it to boost readership during the early days of their century-long rivalry. Durrant himself received bags of fan mail, much of it from female admirers. While Durrant captivated the public, his often-contradictory testimony didn’t convince the jury—the only audience he really needed to sway. The jury found him guilty in just 22 minutes on November 1, 1895.

Durrant’s final public appearance came in San Quentin’s death chamber on January 7, 1896.

“I am an innocent man,” Durrant protested from the gallows at 10:34 a.m. “I bear no animosity toward those who have persecuted me, not even the press of San Francisco, which hounded me to the grave,” he added during a four-minute speech that was described as “poorly constructed” by the press he excoriated. A few minutes later, Durrant was dead.

“After the drop, Durrant did not struggle,” the Deseret News reported. “In fifteen minutes, he was cut down; the neck was broken by the fall.”

After the murders, Mission residents called for the cursed church to be burned to the ground, but again it endured. Even the earthquake of 1906 and the fires that followed failed to take down the building. The church was finally dismantled plank by plank in 1915. City College’s Mission Center stands on this site today.

____________________________________