Experienced park rangers won’t go near the scene of the crime—the site of the White Death disaster, which claimed the lives of nearly one hundred railway passengers and workers. Why not? One reason is that even reaching Stephens Pass, Washington, the site of the deadliest train wreck in American history, isn’t easy. Stephens Pass is in the Cascade Range, and those who want to get there must traverse formidable mountains covered in snow most of the year—from October to July, actually. Not only does the weather present a problem, but so do the deadly drop offs and unforgiving, steep cliffs that would scare a mountain goat. But there’s another reason why folks avoid the accident site. Cliffhangers aren’t the only hazards, so the knowledgeable say. Ghost hunters: put on your hiking boots and snow gear and look no further if it’s ghostly hollows you seek. If the cold doesn’t claim your life before you get there, the fright may.

Strange and bizarre sightings occur at the accident site. Visitors have seen—well, let’s call them people—walking along train tracks and then vanish into the mountain mist. Victims of the crash? No one knows. And that’s not the only supernatural oddity. Want a case of the heebie jeebies? Other travelers have heard haunting sounds, echoes, and strange whispers. Only the howling wind? Something different, unearthly, say witnesses. Visitors also report becoming overcome with ominous and oppressive feelings and emotions—eerie. If you feel goosebumps prickle your skin (not from the cold, though there’s that too), you’re heading in the right direction.

Go ahead, make the climb up the Iron Goat Trail. It’s the only way to get to the accident site—or the scene of the crime, depending on how you look at the historical facts. Just remember that the White Death is not entertainment. The victims of the train catastrophe were real people who died ghastly, needless deaths.

Witness accounts are bone chilling. How did it all start? One word: avalanche!

Charles Andrew, an employee of the Great Northern railway, described the horrific scene:

“It was like White Death moving down the mountainside above the trains. Relentlessly it advanced, exploding, roaring, rumbling, grinding, snapping—a crescendo of sound that might have been the crashing of ten thousand freight trains. The snow consumed the cars and equipment as if they were no more than now-draped toys. The mass of white swallowed everything up in its path and disappeared like a white, broad monster into the ravine below.”

No surprise that the tragedy has been labeled White Death. Maybe it should’ve been called Certain Death. Even the railway workers and common laborers knew that once this railway was built, danger would loom from above. The Cascade Range was a major challenge to climb on foot or one horseback; the idea of engineering and constructing a railway line seemed impossible. That didn’t that stop the Great Northern Railway and James J. Hill, the railroad magnate, from building Stevens Pass in 1891. Arrogance, perhaps? Did he honestly believe man could prevail over the hazardous conditions of nature? Or did greed motivate Hill and his cohort—the need to move freight and passengers across the country in less time, all the while disregarding the obvious danger to passengers and crew. Probably both arrogance and greed.

In the beginning, workers constructed switchbacks through the mountains to ease the steep assent into the mountains. In 1897, they began work on the Cascade Tunnel to ease the way. They believed that a tunnel would be safer to travel through and—get this—reduce the risk of trains coming into contact with avalanches. Opening in 1900, the two-and-a-half-mile tunnel had its limitations. Avalanches continued to occur and block the entrances. Moreover, as trains ascended and descended the mountain, their fire-powered engines would kick off embers and frequently burn the timber and wooded lands in the area near the tracks. A simple backyard physics experiment will easily prove that exposed tracts of land provide little or no protection against sliding snow. With nothing to stop the snow from barreling down the mountainsides—a disastrous example of the snowball effect—it’s no wonder that avalanches like the White Death intensified in strength as the snow plummeted down the deforested slopes.

Let me tell you a haunting story—a believe-it-or-not type of story and a real-life thriller. You decide if a crime was committed.

Let me tell you a haunting story—a believe-it-or-not type of story and a real-life thriller. You decide if a crime was committed.On February 23, 1910, two Great Northern Trains, the Spokane Local passenger train No. 25 and the Fast Mail train No. 27, carrying fifty passengers and seventy-five employees, left Spokane and traveled westbound toward Seattle. The trains ascended the mountains and had emerged from the Cascade Tunnel, exiting on the west end. The weather became angrier and angrier. Snow blizzards and avalanches forced the trains to stop near the small railway town of Wellington. The trains remained under the peak of Windy Mountain just above Tye Creek. The crew could do nothing but wait for snow plows to clear the tracks. Four locomotives equipped with snowplows headed out to help. One got stuck and couldn’t refuel, and another hit a tree stump and was damaged. More avalanches and snow built up blocked the last two plows from reaching the trains. Worse, the railroad’s “shoveler employees” were out of commission. They’d all been fired after mixing it up with the company in a wage dispute. The Wellington telegraph lines went down, and communication with the outside world was lost. Snow continued to rain down, piling up in snow drifts—eight feet high, maybe higher. Six long days passed. Tempers were rising. All anyone could do was to sit tight and wait out the storm.

John H. Churchill, a Great Northern Railroad brakeman, said, “The coal was running short, and the supply in the bunkers was used up, and what little coal we had was needed to keep the trains warm so the passengers would not suffer from exposure. …”

The story gets more harrowing. On February 28 and into the early hours of March 1, the snow turned to rain. Thunder and lightning bombarded the mountains. Witnesses said they’d never seen a storm of this magnitude.

Walls of snow came loose and barreled down the slopes around 4:00 a.m. The barren mountain landscape, denuded of trees as a result of fires caused from the embers of passing trains, provided the perfect conditions for a super-massive snowslide. Once the snow funneled its way into this flattened land corridor, nothing held it back. With gravity at work, there was only one way for the mass of snow to travel and that was down.

Two Great Northern Trains, like sitting ducks, were in the direct path of danger. Most of the people onboard those trains were tucked away in cabins asleep and knew for naught of their fates. The massive avalanche of snow, which was ten feet high (some say as much as fourteen feet high) and a quarter of a mile wide, plummeted down the mountain and struck the two trains, complete with five or six steam and electric engines, fifteen boxcars, and multiple passenger cars and sleepers. Both trains were mercilessly thrown down into Tye River gorge 150 feet deep. Mangled and twisted, the trains were buried under forty to seventy feet of snow.

William Edward Flannery, Great Northern Railroad telegraph operator, who was staying in Wellington, reported that, “At 12:05 I woke up and saw a flash of lightning zigzag across the sky, and saw another, and then there was a loud clap of thunder. The next thing I knew I heard somebody yelling. We got up and climbed down on the bank to where the trains had been knocked by the slide … I saw a man lying on the snow and I went and got him, and put him on my back … and while I started up the hill, another slide hit and knocked me down underneath it, and I lost this man, I was sort of dazed and was underneath the snow some ten or fifteen feet. I started to dig and climb out along the side of a tree, and finally got out, and I was in such a dazed condition that I walked down and walked into the river up to my shoulders, when I came to and realized what I had done.”

Those who feared the worst were, unfortunately, validated. Ninety-six people perished and only twenty-three survived but suffered injuries. Hundreds of volunteers and railway workers came to help dig out the victims. It proved a gruesome task. Some of the bodies were unrecognizable and never identified. The dead were packed onto toboggans and taken down the mountain.

It took only three weeks after the tragedy to repair the tracks. The railroad did take some safety measures. By 1913, the Great Northern Railway completed construction on snow sheds to protect trains from snow slides in problem spots. One of these sheds was even made of concrete. The railroad constructed a second tunnel through Windy Point. But snow slides continued to occur, and the danger to travelers from potential avalanches remained. Not until 1929 did the railroad consider the safety of passengers and crew and reroute their railway by digging an eight-mile-long tunnel through the mountains, the longest tunnel yet.

Remarkably (or maybe not so remarkably given the enormous political power of the railroads at the time), the courts found that the Great Northern Railway hadn’t acted with negligence—much less with criminal intent—despite knowing the railway was constructed on dangerous ground, that avalanches were a problem, and that the locomotives were spewing fiery embers into the forest leaving fires in their wake that cleared the land making avalanches more deadly. Rather, the court decided that the disaster was caused by an act of God. Yet top brass at the railroad must’ve known this type of disaster was going to happen. They simply chose to ignore the risk. Take a look at the corporate symbol of the Great Northern Railway—a mountain goat standing on a rock. How did a railway come up with a logo like that? Just think about what a locomotive of yesterday might’ve looked like climbing rocky mountainside grades and you’ll have your answer. Any rational railroad person knows that trains aren’t mountain goats.

The White Death remains one of the eeriest tragedies ever. Think about it. One minute you’re tucked comfortably in your railroad berth, breathing air, and the next (depending on your views of the afterlife), you’re either buried under a mountain of snow, waking up in the arms of an angel or lost wandering Stephens Pass trying to figure out if you’re dead or alive and hoping you’ll wake up from some horrifying nightmare.

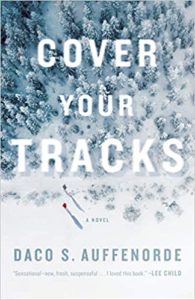

Train wrecks and avalanches are a deadly combination and also the inspiration for a survival thriller. My novel Cover Your Tracks (Keylight Books, October 20, 2020) begins when a train collides with an avalanche while traveling through an isolated section of the Rocky Mountains. Only two people live. The novel explores the seemingly random whims of Mother Nature and how human beings will use every ounce of strength to overcome devastating obstacles to save themselves and those they love.

***