One of the joys of writing historical fiction is that you get to meet so many interesting people. And I don’t mean other writers, I mean you get to meet people from history—and not only meet them, but recreate them too, and give them your words and introduce them to readers of today.

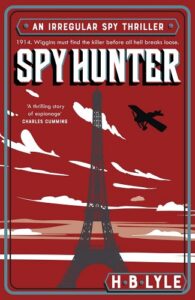

In my Irregular series of books, I took the hero Wiggins from fiction (he was a street-kid assistant of Sherlock Holmes from the Conan Doyle stories), grew him up but then placed him in real history. He does still interact with Holmes but most of the people he interacts with were real. In his latest adventure, Spy Hunter, he becomes entangled with Mata Hari – the ‘exotic’ dancer executed for spying in 1916—just the latest in a long line of colorful characters that peopled the Europe and America of the early twentieth century.

Mata Hari was a legend in her own life-time, a self-styled exotic dancer supposedly trained in India, she used a combination of potent perfume, revealing costumes and a powerful personal charisma to beguile first the music and dance halls of Europe and then the ever-more exclusive salons of the rich. This was the self-created legend, but behind that façade lay a sadder more prosaic truth. Born Margaretha Zelle in the Netherlands, she married an army captain and went with him to Indonesia, then a Dutch colony. The marriage was unhappy, and Margaretha was mistreated physically and emotionally. By the time she divorced, she’d almost certainly contracted syphilis from her husband.

This didn’t stop her remarkable rise in the dance halls of France and beyond, bringing an artistic and semi-respectable sheen to the previously disreputable pastime of ogling women while they danced with little on. Her death, too, became the stuff of legend when she was (probably falsely) convicted of spying against France and executed by firing squad. Almost immediately, stories of the dancer-spy made their way into print and onto the big screen, starring the likes of Greta Garbo and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

While the extent of Mata’s spying is open to debate, the same cannot be said for the two upper-class idiots Wiggins meets in his second adventure, The Red Ribbon. Captain Bernard Trench and Lieutenant Vivian Brandon were a pair of Royal Marines officers who fancied a bit of amateur spying in their down time. Inspired by the Erskine Childers book The Riddle of the Sands, the dynamic duo secured official funding to take a jaunt over the channel, scoping out German coastal defences in 1910.

This involved taking notes, sketches and, of course, photographs. Taking photographs of naval bases, that is. At night. With a flash. Of course, these bumbling fools—more Jonny English than James Bond—were caught, despite Wiggins’s best efforts. They spent the next three years in prison, a rarely remarked upon embarrassment for the British Secret Service.

Many of the other characters Wiggins meets are not so harmless. In the first two books, he falls in with an anarchist gang led by Peter the Painter—a semi-mythical figure of the East End of London, a Latvian, supposedly behind a slew of terrorism in 1909/10 but never actually caught. Even his very existence is sometimes disputed, unlike his friend Yakov Peters—who was acquitted at the Old Bailey in 1911 for his role in the gang murders, and went on to become deputy head of the Cheka, the first incarnation of Communist Russia’s secret police.

It is on the streets of New York in 1912 where Wiggins comes across some of the most colorful characters of his adventures so far. Not only do they have names like Gyp the Blood, Lefty Louie and Big Jack Zelig—these people actually lived up to those names. Gyp and Lefty were two ‘stick men,’ assassins in the employ of Zelig, who terrorized the stuss joints and saloons of Manhattan. Zelig, a tall man with a small hat, lorded it over the Lower East Side until he, too, met a grisly end—shot in the back of the head as he rode north on the 2nd Avenue streetcar.

And it’s not just the gangsters that provided the outsized criminal behavior. Lieutenant Charles Becker of the NYPD, a man mountain and head of a crime squad that patrolled midtown between 23rd and 42nd Streets between 5th and 7th Avenues. The area was known either as the ‘Tenderloin’ because of the rich pickings for anyone on the graft, or more luridly Satan’s Circus to reformers who wanted to clean up the vice capital of America. Becker was convicted of procuring the services of Gyp the Blood, Lefty Louie and Zelig to commit the murder of Herman Rosenthal outside the Hotel Metropole in 1912. It took three years, but eventually Becker went to the electric chair in Sing-Sing as the first— and so far only—American cop to be executed for murder.

Even if you don’t build whole narratives around real-life figures, it can be fun as a writer to drop in the famous and not so famous characters as little cameos. Winston Churchill appears in the three of the books, not as the portly, cigar-wielding older man who led Britain in World War Two, but the younger, prematurely balding, hyper ambitious, rather petulant thruster who was big in the Liberal government before being disgraced after the failed military campaign in Gallipoli (and crossing back to the Conservative party.)

I’ve given walk-on roles to Kennington native Charlie Chaplin, before he made it in the movies and to Captain ‘Titus’ Oates aboard the Terra Nova, on his way to accompany Scott to their deaths at the South Pole. At one point, Wiggins is rescued by a very capable, indeed inspirational, lesbian called Rose Schneidermann who, in addition to being a powerful trade unionist and suffragist, when on to co-found the American Civil Liberties Union.

Not only figures of history, but writers too make an appearance. Perhaps my favourite scene of all the Irregular novels has Damon Runyon—known only as ‘Baseball’ in The Year of the Gun—introduce Wiggins to Arnold Rothstein, the man who fixed the 1919 World Series. Runyon is my favourite short story writer, and I loved imagining what he might have sounded like as a younger man (based on the language of his stories.)

I managed to squeeze in another of my writing inspirations into the same book, the aforementioned Erskine Childers— referred to only as the ‘Civ’, a nod to his job as a civil servant. I wrote about Childers for Crime Reads, but suffice to say that not only was his writing a key moment in spy and adventure fiction, but he also had a crazy life of action, subterfuge and ultimate tragedy—a life that ended, like Mata Hari’s, at the hands of a firing squad.

Finally, as someone who ripped a character from classic fiction and placed him in the real world for a whole series of books, I cannot resist doing it every now and then with other fictional characters. In addition to Wiggins, there’s Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson of course—as older men. In my first book, The Irregular, I also gave a walk-on role to the gentleman thief Raffles and his duffer side-kick Bunny (created, incidentally, by Arthur Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law.)

In my latest book, Spy Hunter, there’s even a role for the chief of the Brussels police, a small man who is very particular about his moustaches and who likes to refer to his brain as the little grey cells.

Now, you don’t have to be a great detective to work that one out.

***