The dictionary defines meta-fiction as “fiction in which the author self-consciously alludes to the artificiality or literariness of a work by parodying or departing from novelistic conventions and traditional narrative techniques.”

I hate articles that begin with dictionary definitions.

It’s a schoolboy technique. Your despotic teacher has forced you to write five hundred words on something you know nothing about. You haven’t got the faintest idea where to start. So you pluck a word out of the title and reach for the dictionary. At least that kills the first few lines of your essay with the added bonus that if it’s in the OED it must be right.

Actually, what I have just given you in these first two paragraphs is my own take on meta-fiction. Here I am on my side of the computer and there are you on the other side of the Atlantic and I have broken down the wall between us, making you aware of me as the writer, questioning my own technique. It’s either entertaining or infuriating, depending on your point of view but I have to say that I’m finding it a wonderfully refreshing way to reappraise the whodunit.

Let me explain.

My latest murder mystery, The Word is Murder, has just been published in the USA. It concerns a detective, Daniel Hawthorne, who has been called in as a consultant to solve a particularly complicated murder in West London. He has decided to hire a writer to produce a book about his investigation. He needs the money and they will split the profits fifty fifty.

The twist is that the writer he has chosen is the author of Foyle’s War and the Alex Rider series…me! I am therefore a character inside my own book, commenting on the action as well as (reluctantly) participating in it. I do not particularly like Hawthorne, at least not to begin with. I find some of his attitudes questionable in the extreme. He is passive aggressive. He smokes twenty cigarettes a day. And he calls me Tony.

As the title suggests, The Word is Murder is as much about writing as it is about murder mystery. It was influenced by two wonderful books that have had a huge influence on me in my career: Stephen King’s On Writing and William Goldman’s Adventures in the Screen Trade. As the author of almost fifty books, I wanted to examine my own craft. How are whodunits constructed? Why do we read them? Are modern trends—cultural appropriation, political correctness—changing the way we approach literature both as writers and readers? I had already written Magpie Murders in which the author of a series of bestselling crime novels was himself killed. The Word is Murder, which is planned to be the first in a ten-book series, was the natural extension.

***

The term meta-fiction was coined by an American novelist and philosophy professor, William Gass, in 1970 but although he was the first to identify the genre, it actually finds its origins long before. Even in the fourteenth century William Chaucer wrote his prologue to the Canterbury Tales, imagining himself into the pilgrimage undertaken by his fictional characters:

So hadde I spoken with hem everichon

That I was of hir felawshipe anon,

And made forward erly for to ryse,

To take oure way there as I yow devyse.(I’d talked to everyone

and quickly became one of their company.

I had promised to get up early with them

and to take to the road as I’m now telling you.)

Don Quixote, written by Cervantes in 1605, takes the conceit several steps forward. The crazed knight is fully aware that he is going to appear in a book and constantly comments on it. In a later sequence he and Sancho Panza visit a printer’s shop where they are disgusted to find a knock-off sequel to their own adventure. Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759) is an elaborate literary joke (though one I always found painfully unfunny) full of self-references, and in the nineteenth century, Thackeray and Trollope regularly interrupt their narratives to address the reader directly.

Bret Easton Ellis made himself the central character of Lunar Park and J.G. Ballard introduced himself into The Atrocity Exhibition but I can’t think of a modern, populist crime novel that has used the tricks and techniques of meta-fiction which is odd because they actually sit very comfortably together. After all, what is a whodunit but an elaborate game between the author, the detective and the reader?

After all, what is a whodunit but an elaborate game between the author, the detective and the reader?The author sits comfortably on top of a mountain, surveying the entire literary landscape. He (or she) knows everything. The crime has actually, necessarily, been solved long before the first word of the book has been written. Every clue is in place. But carefully, the author arranges things so that although the readers cannot feel cheated, the central narrative is obscured. The murderer is both conspicuous and invisible. There is a constant tension between the need to present all the facts fairly whilst at the same time concealing them. (It occurs to me that The Murder of Roger Ackroyd is actually a masterpiece of meta-fiction although Agatha Christie would never have described it that way.)

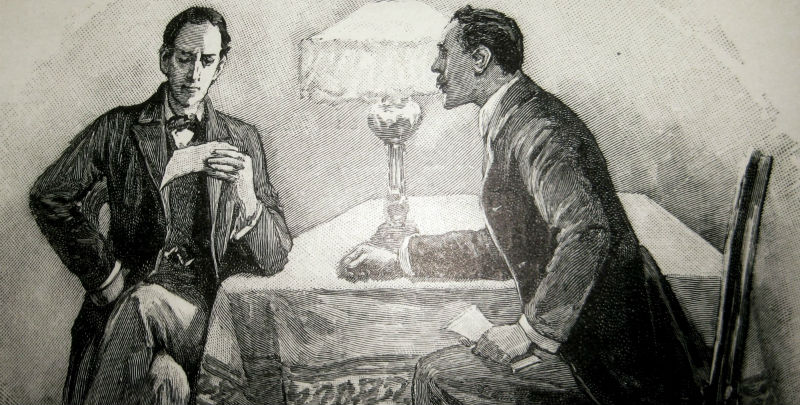

Then there’s the detective, endlessly teasing the reader, knowing everything but revealing nothing. “You see but you do not observe,” Sherlock Holmes famously said, to which my response has always been—so why don’t you tell us? Poirot frequently plays exactly the same trick, mentioning something he has seen or something someone has mentioned that is crucial to the solution but which he infuriatingly refuses to define.

The reader tags along helplessly, always shoulder-to-shoulder with the detective and yet, paradoxically, several steps behind. It was Conan Doyle’s genius to invent the sidekick, the kindly Dr Watson, who takes our side and makes us feel less badly about ourselves by failing, so unfailingly, in solving the crime. Despite some film representations, it’s important to note that Watson is not stupid. Quite the contrary. It’s because he is so intelligent that we trust him to be our guide even though, somewhere in the back of our mind, we know that nothing he ever says, sees or does will help us in any way to solve the crime.

***

When my publishers approached me to write a (hopefully) long-running detective series, my immediate thought was: who would be my detective? Male or female, fat or thin? What ethnicity? Would he/she be depressive, drunk, disabled, married, single, gay? But even asking these questions, it struck me I was only rearranging the furniture, that the books would be little more than a variation on a very old theme. Why would I want to spend seven months writing 90,000 words that led only to “the butler did it”? Why would you want to spend a week reading it?

Meta-fiction has its dangers. At its worst it can seem clumsy and self-important. It can actually distract the reader from the pleasure of solving a good puzzle. But I had enormous fun writing The Word is Murder and I’m already half-way through the sequel, Another Word for Murder. I feel that I’m actually finding something completely new to do within the genre and I’m really looking forward to continuing my association with Daniel Hawthorne.

I just wish he’d stop calling me Tony.