One winter day a long time ago, a handsome woman in her early forties was found dead in a snowbank off a highway in northwestern Pennsylvania. She had been strangled. The homicide was big news around Erie, Pennsylvania, where I grew up. The killer, it was soon revealed, was a man the victim had begun dating after her marriage turned to ashes. For weeks, the crime was grist for newspaper headlines and chatter in barbershops and saloons. It was even featured in the true-crime pulp magazines of the era.

The victim was my mother’s sister.

I recall the coffin being wheeled out of a candle-scented church as a choir sang farewell and my aunt’s relatives stood grim-faced, some with tears on their cheeks. I was in college at the time, old enough to understand that I had been granted wisdom not bestowed on everyone. I understood that a murder spreads an indelible stain, dividing the lives of people close to it into Before and After.

So began my interest in crime. It is an interest that has only deepened with the passage of years. It has compelled me to read scholarly tomes as well as lurid accounts of sensational cases. It has drawn me to courtrooms and prisons and to the death house in Texas, where I witnessed the execution of a pathetic, dirt-poor man who had raped and killed his ex-wife and her niece in a drunken rage.

***

My preoccupation with crime was known to my editors during my newspaper career. Thus, on January 12, 1974, an arctic cold Saturday in Buffalo, my bosses at the Buffalo Evening News sent me to the Federal Building for a somber announcement by the resident FBI agent. The fourteen-year-old son of a wealthy doctor in Jamestown, New York, sixty miles southwest of Buffalo, had been kidnapped the previous Tuesday. Three teenagers had been arrested Friday, and most of the ransom money had been recovered in the home of one of them.

But the boy was still missing.

The FBI agent told reporters that the bureau had entered the case because the victim had been missing for more than twenty-four hours. Ergo, there was a presumption under the Lindbergh Law that he might have been taken across state lines, so the feds were authorized to assist the local cops.

I knew about the 1932 kidnapping and murder of the infant son of legendary aviator Charles A. Lindbergh. So I assumed that horrible crime inspired the law.

Not exactly.

I was surprised to learn that, despite acquiring its informal name from the Lindbergh crime, the Federal Kidnapping Act of 1932 was a reaction to a string of abductions that began before the Lindbergh baby was even born and continued while he was still squirming happily in his crib.

_______________________________________

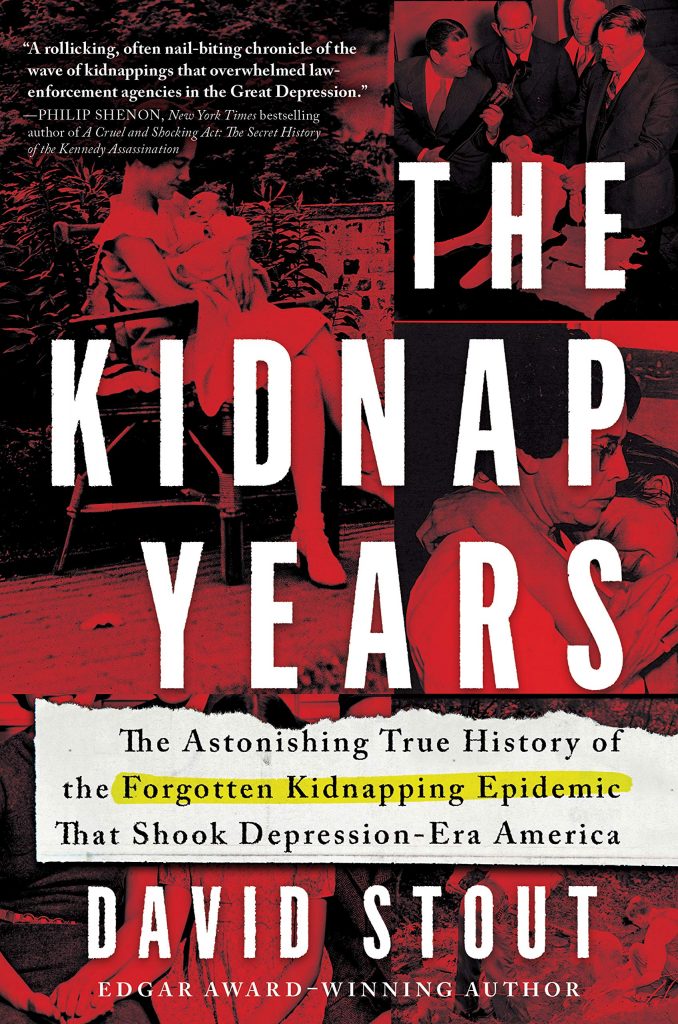

You are reading an excerpt from The Kidnap Years: The Astonishing True History of the Forgotten Kidnapping Epidemic That Shook Depression-Era America, by David Stout.

_______________________________________

There were so many kidnappings in Depression-era America that newspapers listed the less sensational cases in small type, the way real estate transactions or baseball trades were rendered. There were so many kidnappings that some public officials wondered aloud if they were witnessing an epidemic.

In fact, they were.

From New Jersey to California, in big cities and hamlets, men and women sat by a telephone (if the household had one) or waited for a postman’s knock, praying that whoever had stolen a loved one would give instructions for the victim’s deliverance. There was usually a demand for money, sometimes for a fantastic sum, other times for a small amount that might even be negotiated down. It was possible to put a dollar sign on the value of a life.

A family’s ordeal might last for hours and end happily. Or it might go on for days, with the relatives knowing that as time passed, hope ebbed. For some people, the ring of the phone or the knock on the door brought heartbreak and bottomless sorrow—the very emotions visited upon the family in Jamestown, New York, in 1974.

***

There was never much mystery behind the Jamestown case. The instructions for delivering the ransom were simple and unimaginative, giving investigators plenty of time to stake out the drop site and photograph whoever picked up the money. The ransom demand was a mere $15,000, a fraction of what the doctor’s family could have paid.

The amateurish nature of the scheme had caused investigators to suspect early on that the crime was the work of local teenage dim bulbs. Sure enough, teachers at the area high school easily identified the youth who had been photographed picking up the money. He was a supervisor at a teen center where the doctor’s son had said he was going just before he vanished. The voice on a tape-recorded call to the doctor’s home was recognized as that of a nineteen-year-old high school dropout who hung out at the teen center.

When two eighteen-year-olds were arrested, they admitted they’d done something wrong under the guidance of the nineteen-year-old, but they swore they hadn’t signed on for anything that might bring harm to the boy.

Ominously, the nineteen-year-old, in whose home the ransom money was found, kept quiet about the boy’s whereabouts. Searchers combed the snowy woods around Jamestown on Saturday and Sunday until the boy’s body was found lashed to a tree. He had been beaten to death, probably with a metal pipe or a hammer judging by the wounds to his head.

Since the kidnapping and slaying had obviously occurred within New York State, the FBI bowed out, leaving the state prosecutors and courts to mete out justice. The two eighteen-year-olds got off with light punishment. But it was the nineteen-year-old who got the biggest break of all. When he went to trial on kidnapping and murder charges, his lawyer argued that there was insufficient evidence to convict him of murder. After all, no one had seen the suspect with the victim from the time he vanished until his body was found in the woods.

The jurors pronounced themselves hopelessly deadlocked, so a deal was worked out under which the nineteen-year-old pleaded guilty just to kidnapping, which meant a sentence of eight to twenty-five years instead of the twenty-five-to-life term he could have gotten for the murder count alone.

Had I been on the jury, I would have tried to cut through the fog. “Let’s use our common sense,” I would have said. “Of course he killed the kid. If he didn’t, who the hell did?”

But the truth doesn’t always count for much in a courtroom, as some lawyers try to inject reasonable doubt into cases in which there is none.

***

Viewing a time in history from the vantage point of the present is a bit like being in an airplane and gazing at the ground from two miles up. It is too easy to miss the trees while looking at the forest. Most of the kidnappings from long ago are little remembered today, but they defined the times as much as bank robberies and speakeasies and panhandling.

They spurred new laws and new law-enforcement techniques, like criminal profiling. They brought out the best qualities in some lawmen, like endless persistence and ingenuity, and the worst in others: carelessness, cruelty, even brutality.

The kidnappings also helped to expose the corruption, the moral rot, that infected city hall and police headquarters in some communities in the 1930s

Indirectly, the kidnappings also helped to expose the corruption, the moral rot, that infected city hall and police headquarters in some communities in the 1930s, as shown by the fact that some victims were rescued by gangsters while complacent or corrupt police officers watched from the sidelines. Eventually, public disgust helped to spur reforms as people belatedly realized that the mobsters among them were not just colorful rogues but robbers, parasites, pimps, even killers—the kind of people who made kidnapping profitable.

Some people who survived kidnappings were able to treat their times in captivity as excellent adventures (once they had bathed and changed clothes). But most were emotionally scarred, even if they did not realize it at first. Others were damaged for life.

***

As the false glitz of the 1920s yielded to the crushing poverty of the 1930s, kidnappings became so frequent in the United States that newspapers could scarcely keep up with them, as evidenced by a front-page article in the New York Times on Tuesday, July 25, 1933. The article reported the arrest of several Chicago gangsters for the kidnapping of a St. Paul, Minnesota, beer mogul who had been freed after a ransom payment. The article noted that lawmen expected to link the gang to another Midwest kidnapping. And it alluded to an attempted kidnapping on Long Island.

The article was continued on page 4, a “jump page” in newspaper parlance. There was also an article on page 4 about the kidnappings of an Oklahoma oil tycoon and the son of a politician in Albany, New York. There was a report about a Philadelphia real estate broker who was shot dead in a bungled kidnapping attempt. Finally, there was a list, rather like a scoreboard, of some recent cases in which victims were rescued and suspects were apprehended:

Mrs. E. L. (Zeke) Caress, Los Angeles; Dec. 20, 1930, three in prison for life, twenty-two, and ten years.

Sidney Mann, New York; Oct. 13, 1931; three in prison for life, fifty, and twenty years.

Mrs. Nell Quinlan Donnelly, Kansas City; Dec. 16, 1931; two in prison for life; one for thirty-five years.

Fred de Filippi and Adhemar Huughe, Illinois; winter, 1931; two in prison for forty-two years; one for twenty; two others for two years.

Benjamin P. Bower, Denver; Jan. 8, 1932; three in prison for six and one-half years.

James DeJute, Niles, Ohio; March 2, 1932; two in prison for life.

Haskell Bohn, St. Paul; June 30, 1932; suspect awaiting trial.

Jackie Russell, Brooklyn; Sept. 30, 1932; two in prison for four to twenty-five years.

Mr. and Mrs. Max Gecht, Chicago; Dec. 10, 1932, two in prison for life.

Ernest Schoening, Pleasantville, N.J.; Dec. 27, 1932; five in prison for five to twenty years.

Charles Boettcher Jr., Denver; Feb. 12, 1933; two in prison for twenty-six and sixteen years.

John Factor, Chicago; April 12, 1933; two suspects held.

Peggy McMath, Harwichport, Mass.; May 2, 1933; kidnapper in prison for twenty-four years.

Mary McElroy, Kansas City; May 27, 1933; two held; two more sought.

John King Ottley, Atlanta, Ga.; July 5, 1933; guard arrested.

August Luer, Alton, Ill.; July 10, 1933; four men and two women under arrest, after confession by one of the men.2

***

What spawned the kidnapping epidemic? Prohibition, which was ostensibly intended to eradicate domestic violence, workplace injuries, and other social ills associated with drunkenness, has been blamed not just for creating a vast new liquor-supply business for organized crime but for fostering, even glamorizing, a general spirit of lawlessness. But it can also be argued that the approaching end of Prohibition contributed to the spate of kidnappings. After all, what was an honest bootlegger or rumrunner to do when his trade became obsolete?

Or perhaps something much deeper was going on. For all the talk about economic inequality in twenty-first century America, the chasm between rich and poor was far wider in the 1930s. A man was lucky to have a job, any job, while less fortunate men were standing in bread lines and housewives were serving ketchup sandwiches for dinner and boiling bones to make thin soup.

And if a person was born to wealth, he or she might be hated by those on the bottom rung of society. Almost surely, some kidnapping victims suffered because they had what their abductors could never have: money and self-esteem. And freedom from worry, perhaps that above all. Nowadays, people know that recessions come and go, that prosperity will return as surely as the seasons will change. But in the Great Depression, that kind of optimism, that certainty, was inconceivable to many people.

Travel back in time via newspaper microfilm to the 1930s, and you sense the fear and sorrow and violence of those years. In the depths of the Depression, bank robbers roamed the country. They were new Robin Hoods to some Americans, especially those who lost their savings when banks failed or were terrified of losing their homes or farms to foreclosure.

To read the news from that time is to sense that the very fabric of American society was being torn apart.

To read the news from that time is to sense that the very fabric of American society was being torn apart. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous line, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” delivered at his first inauguration in 1933, offered a flicker of hope to a people in need of hope. It just wasn’t true.

“Every day, the children seemed to grow more pale and thin,” an impoverished Chicago city street sweeper said a few weeks after FDR took office. “I was working only four days a week and had received no pay for months.”

The street sweeper was explaining to the police why he fed his starving family meat from a dead pig he had found in an alley behind a restaurant. He sampled the meat, and it didn’t seem to harm him. So his wife and their ten children also ate. Soon, two of his children died of food poisoning. Within days, two more of the children were dead. When the street sweeper told his story, he was said to be gravely ill, as were his wife and some of their remaining children. I wanted to know if the mother and father and their children survived, but I could not find out. Not long after the initial reports, the newspapers in Chicago and elsewhere seemed to tire of the family’s ordeal. Or perhaps the journalists simply lost track; the family was Italian, and the name was spelled at least two ways in the coverage.

Besides, the Great Depression offered countless stories of suffering and death. No need to dwell on the troubles of a lowly street sweeper and his family, not when some broken men were committing suicide and others were abandoning their families and hopping freight trains to nowhere.

***

Not all kidnappings stirred public revulsion. On the contrary, a juicy gangland kidnapping could be as entertaining as a newspaper photo of a slain mobster with his head resting in a bowl of pasta and his blood mingling with spilled wine.

Newspaper reporters and editors indulged in considerable levity as they chronicled the snatches and ransom negotiations involving people on the wrong side of the law. Even the New York Times, that stuffy bastion of good taste and prudery, got into the spirit now and then. Reporting on one case in the thirties, the Times noted lightheartedly that Basil Banghart, a Chicago gangster and machine-gun artist known to friend and foe as “the Owl,” had been sentenced to ninety-nine years in prison for his role in a kidnapping. (A fellow mobster explained Banghart’s nickname: “He had big, slow-blinking eyes—and he was wise.”)

Around the same time, the newspaper noted breezily, another Windy City miscreant, Charles “Ice Wagon” Connors, was kidnapped and “taken for a ride” to a patch of woods where he was shot to death by former associates after a falling out—over money, of all things. (In mob legend, Connors acquired his nickname as a good-natured joke: a getaway car he was driving collided with an ice-delivery truck after a robbery. The historical record is unclear as to whether he got away anyhow.)

The laughter stopped on the night of March 1, 1932, with the most famous kidnapping in U.S. history, that of twenty-month-old Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., stolen from his parents’ home in Hopewell in rural west-central New Jersey. It was called “the crime of the century.” It is hard to imagine, in our age of debunking and social media sniping, the adoration that was heaped upon Charles Lindbergh after his epic 1927 flight to Paris. He was idolized for his great courage in flying alone over the Atlantic Ocean, for his matinee idol good looks, for a half smile that suggested an underlying modesty and not the aloofness that really lay behind the façade.

“Had not Charles A. Lindbergh flown the Atlantic…a federal kidnapping statute might not yet have been enacted,” a commentator observed after the anti-kidnapping law was passed by lawmakers and signed by President Herbert Hoover in June 1932.

Yes, the ordeal of the Lindberghs roused Congress from its torpor. But well before March 1, 1932, it seemed that people who were not necessarily famous nationally but were well-to-do—brewers, bankers, builders, and merchants—were in danger, as were their children.

While there is no empirical way to gauge a nation’s collective emotion, it may be that the kidnapping and slaying of the golden-curled Lindbergh baby caused more grief, revulsion, and yearning for retribution than any other crime against a private citizen, adult or child, ever.

Charles Lindbergh Jr. was an adorable baby. His heroic father was the son of a former congressman. Charles Lindbergh’s shy, pretty wife, Anne, was the daughter of Dwight Morrow, a wealthy banker, former ambassador to Mexico, and briefly a Republican senator from New Jersey before his unexpected death in 1931 at age fifty-eight.

Before the Lindbergh horror, enactment of a federal kidnapping law was hardly a sure thing. The U.S. attorney general, William D. Mitchell, argued against it on grounds that it would increase federal spending and make the states too dependent on Washington.

But with the discovery of the Lindbergh baby’s body on May 12, 1932, things changed literally overnight. On May 13, President Hoover, ignoring the reality that the U.S. government had no jurisdiction over kidnappings, ordered federal law enforcement agencies to aid state and local investigators “until the criminals are implacably brought to justice.”

Representative Charles Eaton, a New Jersey Republican, was similarly outraged, declaring after the baby was found dead that the Lindbergh family was “the symbol of all that is holy and best in our nation and civilization.”

The chaplain of the House of Representatives, the Reverend J. S. Montgomery, offered a prayer for the child, then urged lawmakers to “arouse the public conscience, that a slight atonement may be made, by smiting murderers and outlaws into the dust.”

At the dawn of the 1930s, taking a kidnapping victim across a state line was a smart tactic. In that predigital era, there wasn’t much coordination and cooperation among the police and courts of the states. Most states did not have statewide police forces. Potential witnesses in a state to which a victim was taken were beyond the subpoena reach of courts in a state where the kidnapping had taken place. Laws against kidnapping varied from state to state. Extradition was cumbersome. Fewer than half of American households had telephones.

And sadly, some local cops augmented their modest incomes by taking money in return for not chasing criminals too aggressively.

What became known as the Lindbergh Law was sponsored by Missouri lawmakers Senator Roscoe Conkling Patterson, a Republican, and Representative John Joseph Cochran, a Democrat from St. Louis. A number of kidnappings had taken place around Kansas City and St. Louis. Both cities were influenced by, some would say run by, organized crime. A lot of kidnappings were carried out by professional criminals who had branched out from gambling, bootlegging, and other illicit enterprises.

But some kidnappings were the work of amateurs, driven to desperation because they had no jobs and no prospects. And some people plumbed the depths of human cruelty by posing as kidnappers, sending ransom demands to relatives of the victims while knowing nothing of the victims’ whereabouts.

What made Kansas City, Missouri, and St. Louis such hotbeds of kidnapping? The first city, of course, is next door to the identically named city in the state of Kansas. St. Louis, which sits on the Mississippi River, was even more ideally situated. Kidnappers could take a bridge across the river and be in Illinois in minutes. And for kidnappers with boats, the mighty river offered access to the entire Midwest. Thus, St. Louis, which was known in frontier days as the “Gateway to the West,” could have been dubbed “the Kidnap Turnstile” in the 1930s.

“Kidnapping is the feature crime of the present time,” Walter B. Weisenberger, president of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce, told the Senate Judiciary Committee as he urged federal anti-kidnapping legislation days after the Lindbergh infant was stolen. “It is a crime that men with some of the best brains in this country have gone into, because it offers big returns and reasonable safeguards.”

Some of the best brains in the country? Perhaps Weisenberger exaggerated the intellects of most kidnappers. But there was no denying that they were an industrious lot. The St. Louis police chief, Joseph Gerk, claimed to have collected statistics from cities nationwide in 1931. He told Congress he had counted 279 kidnappings that year, in the course of which thirteen victims were killed and sixty-nine kidnappers captured and convicted.

But those numbers were unreliable, as Gerk acknowledged. He had sent questionnaires to the police in 948 cities but received replies from just 501. States and cities did not routinely share information with one another, as indicated by the limited cooperation for Gerk’s survey.

The day after the Lindbergh kidnapping, a New York Times article offered a partial list of the most recent kidnappings in various states: Illinois, 49; Michigan, 26; California, 25; Indiana, 20.

The day after the Lindbergh kidnapping, a New York Times article offered a partial list of the most recent kidnappings in various states: Illinois, 49; Michigan, 26; California, 25; Indiana, 20. And so on. The following day, attributing its figures somewhat vaguely to “authorities,” the paper reported that more than two thousand persons had been abducted in the country in the previous two years.

No doubt, many kidnappings went unreported, as some of the victims were criminals themselves, grabbed by rival gangsters, then sold back to their own gangs if they were lucky.

And if they weren’t lucky? A Chicago detective testifying before the House Judiciary Committee in February 1932 let the lawmakers imagine what could happen if negotiations fell through. He told of a raid on a kidnapping ring’s lair that included a “torture chamber,” which apparently had been used frequently and which “hinted at almost unbelievable horrors,” as the Times put it.

Items found in the lair included vats of lime, cans of gasoline, and diving suits.

Why diving suits? Apparently, a captive would be stuffed into one, then lowered to the bottom of the Chicago River and “only infrequently allowed to have air,” the Times reported. Upon being brought up from the cold and total darkness, the victim would presumably have been willing to do whatever his captors desired: agree to stay out of his captors’ territory, beg his employers to pay a big ransom, or both.

And here, the inescapable question: were some kidnappers mean-spirited enough to leave victims at the river bottom until the bubbles stopped?

***

Justice was more streamlined in the 1930s. The courts were far less cluttered by appeals; defendants’ rights that we take for granted today did not yet exist. And if numbers are any indication, there was far less ambivalence about capital punishment. In the 1930s, there were 167 executions a year on average, more than in any other decade before or since, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, a Washington nonprofit organization that collects and analyzes data on capital punishment.

Here, some numbers are illuminating—and startling. In 1935, there were about 127 million Americans; in 2018, there were about 328 million. If executions were carried out nowadays at the same rate as they were in 1935, about 430 prisoners would have been put to death in 2018—roughly eight a week. But since the Supreme Court reinstated capital punishment in 1976, after a four-year hiatus, the highest total of executions in a single year was “only” 98 in 1999, as the Death Penalty Information Center notes.

Why such a parade to the gallows, gas chamber, or electric chair at that point in history? Again, there were fewer grounds for appeals. Probably more important, some criminologists argued that the death penalty was necessary to prevent society from disintegrating.

In the 1930s, the 1901 assassination of President William McKinley in Buffalo by an anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, was fresh in the memories of Americans of middle age and beyond. In Europe, dynasties had been toppled and social norms shattered by the Great War. The Russian Revolution had enflamed fears that “radicals” and “Bolsheviks” were working their mischief within the United States. In fact, there were left-leaning Americans who wanted to bring about fundamental changes in government and society, although it is likely that few wanted to see blood running in the streets.

As a proud alumnus of the New York Times, I was struck by the tone of some of the newspaper’s coverage of events during the 1930s.

Riots in “Negro” neighborhoods stirred speculation that communists and other social agitators were responsible. The lynching of “a Negro” typically merited a few paragraphs, especially if it occurred in the South, where lynchings were too common to be newsworthy. If there was much reporting on whether racial unrest might be linked to the evils of segregation, bigotry, and poverty, I missed it. This was a time when the Ku Klux Klan was still thriving—and parading—and not just in the Old Confederacy.

Labor unrest was also blamed on communists rather than the desire of workers to have more job security and benefits, more food on the dinner table, and an extra sandwich in the lunch pail. Strikers and union organizers were beaten by company thugs who were euphemistically called “security guards.”

***

There was a man who both contributed to the harsh law-and-order atmosphere of the 1930s and fed off it. He was a dour Washington bachelor who had to overcome a childhood stutter and began his career as an obscure clerk. But he was anything but an unimaginative paper shuffler. He had a gift for organization. He also sensed that one could acquire power, sometimes great power, by filling a vacuum and by throwing himself into seemingly menial tasks that others avoided.

When he took a low-level job in the Department of Justice, he saw a need for reliable, centralized information on crime. He also saw a national leadership vacuum in law enforcement. He would move deftly to fill it and to compile statistics that would eventually be helpful to criminologists and lawmen across the country—and to himself as he massaged numbers to attest to the importance of his own job.

He would use his considerable talents to become one of the most famous law enforcement officials and arguably one of the most important public figures in American history.