It started out so innocently, like childhood itself. Instead of naming crime fiction books so people knew that’s what they were reading—sticking a word like killer or murder or even crime in the title—the words started changing. Publishing is a self-reflexive medium, so when a gargantuan hit just happens to be called Gone Girl the marketers and the authors and all of the other foot soldiers in the battle for the next bestseller latch upon the magic word: Girl.

Girl is the perfect word for inspiring curiosity and fear in psychological thrillers: since the Bible, or the Greek myths, the protection of girls has been paramount to holding a society together. Girls, after all, become women, and women birth and raise the next generation, keeping civilization going. So the question here is not why did girl instantly become so popular, but how it reflects on our cultural preoccupation with keeping women—made even more impotent and infantilized by being labeled girls—under patriarchal control.

For now, let’s keep it light: we know that there are way too many girl books for you to remember which ones you’ve read, or someone recommended to you, or you saw, say, on CrimeReads and thought that’s my next read. No worries, I’m doing some heavy lifting for you: two lists of books with girl in the title which should abate confusion for a little while. Bookmark it, print it out and laminate it, or cut-copy-paste it somewhere in your phone. You’re welcome.

Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn (2012)

Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn (2012)

This was indisputably the title that started it all, attached appropriately to the book that transformed thrillers from airport books for middle-aged people to the hippest, slyest, most subversive reads around. Flynn’s previous outings were both solid, but Gone Girl was and is something special: it’s a critique of helicopter child-rearing (our narrator, Amy, is the daughter of authors who wrote a series of books called Amazing Amy), of the barbed territory of dating and falling in love, and, most importantly, of marriage. Flynn is expert at finding tender spots and probing them, whether it’s being falsely accused, being exposed as an adulterer, or secretly resenting the sacrifices all marriages require.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, by Stieg Larsson (2005)

Larson’s book predates Flynn’s but since the translation of the Swedish title is The Man Who Hated Women let’s not count it as a girl book until it came out in English. Larsson introduced the world to an extraordinary heroine, Lisbeth Salandar, in the books that would come to be known as the Millenium series. Salander is a brilliant computer hacker, an excellent fighter, and a general, take no prisoners kind of woman—there is not much girly about her. The first few books in this series suffer from a surfeit of exposition, but Salandar and journalist Mikael Blomkvist make an explosive team, taking down one of the most powerful families in Sweden—and they are just getting started.

Final Girls, by Riley Sager (2017)

The trope of the final girl was first identified by Carol Clover in her brilliant analysis of slasher and horror films, Men, Women, and Chainsaws. She observed that in most of these movies there is a heroine who survives the ordeal—whether it’s a masked serial killer, a run-of-the-mill bogeyman, or a figure who cannot be caught because that interferes with the creation of more movies and minimal work creating a villain. The final girl is also the witness to the chaos that comprises the meat of the novel: the murders, the chases, the hiding in closets and attempts to open windows painted shut. The image Sager provides of the final girl which I felt somewhere deep in my hippocampus: a figure of exhaustion and triumph, of a woman who successfully fought off a monster, usually with her arm up in the air Statue of Liberty style.

All the Missing Girls, by Megan Miranda (2016)

Miranda’s book is gimmicky: it’s told partly in flashback and narrated by several different characters, which I find to be a level of complication not necessary in good crime fiction. It’s an artificial way to build suspense, a not-that-subtle manipulation between the point of view characters and the reader. Grumbling aside, Miranda’s creepy small town thriller is one of the better books about girls missing or gone of the past few years, and that’s a stiff competition.

The Second Girl, by David Swinson (2016)

The Second Girl, by David Swinson (2016)

When I first met David Swinson (whom I do not know well at all so this is not favoritism), he mumbled the name of his forthcoming book because he was so sheepish about being on the girl train. His book does indeed involve around a girl who is kidnapped in the wake of the previous snatching of a girl—hence, the name. But Swinson is a very canny writer with an endless well of life experience (he managed rock bands for a time, and then he was a cop in Washington D.C.) and smarts to lift his simple seeming story into a much more sinister book.

An Anonymous Girl, by Greer Hendricks and Sarah Pekkanen, (2019)

Hendricks and Pekkanen excel at those books where everyone who has power is rich and amoral, but so seductive that the innocent heroines are taken in by these sadistic yet not traditionally dangerous women who run this kind of world—usually in the kind of suburb where everyone has a house large enough to hold a gala or, as in this book, in some fine New York City uptown real estate. This title refers to the fact that our heroine, Jessica Ferris, signed up to be a subject in a study on ethics and morality run by a mysterious doctor, a sophisticate named Dr. Sheilds. Things seem to be going swimmingly until Jessica realizes Dr. Sheilds is trying to engineer an affair between the younger woman and her husband, with her privy to the secrets of both parties.

Pretty Girls, by Karin Slaughter (2015)

Most crime writers would have livid fans if they took too long of a break from a popular series, but Karin Slaughter is not most crime writers. Her standalones are never disappointments, and Pretty Girls is no exception: two sisters, glamorous Claire and single mom Lydia, now adults, have fallen out over the disappearance of their third sister, Julia, who vanished when they were teenagers. Things start to heat up when Claire’s husband is murdered, and both she and Lydia are convinced his killing is related to Julia’s disappearance.

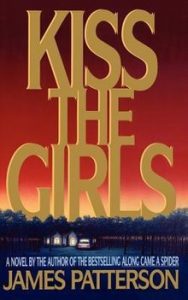

Kiss the Girls, by James Patterson (1995)

Patterson is old school, as is his detective, Alex Cross. In this double-the-fun serial killer classic—Cross’s second outing—Cross is hunting Casanova, who has been murdering women since he was 17 is very active again, abducting a high-profile woman in North Carolina. In the meantime, another serial killer with a case of low self-esteem and a clever nickname, the Gentleman Caller. Thinking about this book in the context of this list, with its sexual violence and its casual misogyny, is recognizing how much the gender problem in crime fiction has and hasn’t evolved: too often some extreme version of the Bechtel test leaps to mind as the men talk endlessly about the missing or dead women and missing and dead women can’t talk at all.