What defines a crime novel? Take your time, it’s trickier to answer than you might think. While you mull it over, let me tell you a story. It’s a quick one, I promise.

A couple of years ago, I finished writing a novel called The 7 1/2 Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle. It’s an Agatha Christie-type mystery in a Groundhog Day loop, except every time my protagonist wakes up he’s in the body of a different suspect—meaning he keeps bumping into future hims and past hims.

The first agent I contacted about representation asked where I envisioned it sitting in the bookstore: under crime or sci-fi. I said crime. After all, it has a big country house, a murdered heiress and more red herrings than a Scandinavian breakfast. She responded by recommending that I dial back the body swapping, time loop stuff because it would ‘muddy’ the book’s appeal.

I’ll admit, that baffled me. I grew up reading cross-genre crime by authors like Terry Pratchett and China Mieville. These are books that don’t just muddy the genre, they throw several cans of paint into it. Crime has it rules, sure, but they’ve always felt like convenience. Authors who choose to write cosy mysteries or procedurals, for example, are choosing to bake with familiar ingredients, knowing that readers like that taste. It doesn’t stop them introducing other flavors, though. Drape the tropes of a cosy mystery over a comedy and it’s a comedy cosy crime novel (somebody please write this!). Put the police in a flying car as they search for a kidnapped character and it’s a sci-fi procedural.

In fact, the idea of a crime writer sticking rigidly to the rules feels like it should somehow disbar them from being a crime writer in the first place—surprise being a crucial element in these stories. That’s why my absolute favorite crime novels are the ones that upend our expectations by using the established rules against us. Agatha Christie did this time and again, as anybody’s who read The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Murder on the Orient Express, Murder in the Mews, or And Then There Were None will testify.

For my blood-soaked money, the definition of a crime novel is simple: if somebody dies, disappears, or has something stolen, and somebody else investigates, it counts. Build that foundation and you can pile as many other genres on top as you’d like.

To prove my point, I’ve picked out nine (ten is traditional, but in the spirit of this piece I’m breaking the rules) books which treat crime as a starting point, telling stories that extend far beyond the body they often begin with. We’ve got metaphysical comedy, activist noir, and other books in the shape of mystery novels

Some are cross-genre, others are just crime +. However you choose to define them, they’re special, strange, and determined to take the genre into unusual territory.

Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency by Douglas Adams

(Metaphysical Comedy)

Crime fiction as metaphysical comedy? Why not. That must have been the thought process of Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, when he decided to point his typewriter at the hardboiled detective genre. This is Philip Marlowe by way of ghosts, possession, time travel, robotic monks and a giant couch impossibly stuck up a flight of stairs. I wouldn’t say the plot travels in a straight line through any of these things, but it doesn’t need to. Our protagonist, Dirk Gently, believes in the “interconnectedness of all things,” which gives Adams leeway to go wherever his imagination drags him. It’s loads of fun. Unlike the television series it inspired.

Murder Most Unladylike by Robin Stevens

(Mystery for Children)

Somewhere between Enid Blyton and Agatha Christie is Robin Stevens, whose Murder Most Unladylike series takes place in a girl’s boarding school where charming schoolgirl detectives Daisy Wells and Hazel Wong battle late assignments and tricky murders.

What makes this book unusual is the density of plotting. Despite being aimed at nine-year-olds and over, Stevens doesn’t simplify her mysteries like other children’s writers. She takes the concepts laid down by Agatha Christie and makes them work for a younger audience, without losing anything in the process.

Honestly, adults will be as baffled as kids, which is an amazing achievement.

So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighborhood by Patrick Modiano

(Meta-detective literary fiction)

Brilliant title, right? The book is worthy of it, though it should be noted that French author Patrick Modiano is more interested in the shape of a mystery novel than the mystery filling it.

The story begins with elderly author Jean Daragane receiving a telephone call from a mysterious man offering to return his address book in return for information on a name inside: Guy Torstel. Daragane claims not to know who this is, blaming a faltering memory. As our mysterious man presses him, we’re pushed deeper and deeper into Daragane’s history, evoking a story that’s part autobiography, part murder mystery and part philosophical meditation on the nature of memory and place. Basically, it’s everything you’d expect from a French Nobel Prize Winning author.

This is How It Ends by Eva Dolan

(Activist Noir)

If a writer of literary fiction and an author of crime fiction met at a party, do you know what they’d talk about? Donna Tartt probably, but, after that, I guarantee they’d get onto Eva Dolan’s book. It’s as much an in-depth character study of two woman at different points in their life, as it is a crime novel—and one that should have graced many more awards lists than it did.

This Is How It Ends is centered on Molly and Ella. Molly’s an old-school social activist looking back over her worthy, if slightly empty life, while Ella’s her young protégé and surrogate daughter—a passionate campaigner who’s a little more interested in social media than social activism.

A murder at the beginning of the story buries them under the same secret, until it becomes clear they’ve both kept important things from the other. Somehow, Dolan manages to weave a commentary on the ills of urban development and a politicized police force with the pace of a thriller. This is a beach book you can recommend at book club.

You Don’t Know Me by Imran Mahmood

(Breaking the Fourth Wall)

As I said in my introduction, to qualify as a crime novel I reckon a story needs a crime and somebody investigating it. You Don’t Know Me heeds that mandate in a really special way—it makes the reader the investigator, and the narrator both the witness and potential hero/villain.

How clever is that?

The plot runs like this: an unnamed defendant is in court accused of murder. His lawyer is about to make his closing argument, when the defendant decides to tell the story instead. This book imagines the reader is on the jury, hearing the story, leaving you to decide whether his story, which increasingly pushes the boundaries of credibility, is true.

All at once, this is a book about the intricacies of the criminal justice system, a look at gangland London, and an amazing character piece. Be warned, the unnamed defendant’s voice will take a seat in your head for a full week after you’ve finished it.

The Shining Girls by Lauren Beukes

(The Sublime Meets Serial Killers)

Serial killers are an off-the-shelf villain for authors. We take one down, screw up their childhood, then splash a bit of swagger over them. It’s Hannibal Lecter’s fault, I’m certain of it. Lauren Beukes did not do this.

Beukes’s serial killer is a 1920s hobo who comes upon a strange house with the ability to transport him to different periods through time. In return, the house compels him to kill extraordinary women, so he travels through time hunting down these Shining Girls. Kirby Mazrachi is one of these girls, and when she survives the attack, she decides to do some hunting of her own.

It’s very tense, very violent, and exceedingly well researched—with every period stuffed with detail. One word of caution, though. Beukes uses her time-travel house as set-dressing, so if you’re one of those people who needs to know why everything is happening, this book will leave you stamping your feet.

The City and the City by China Mieville

(Sci-fi Procedural)

The two cities referenced in the title of this novel are Besźel and Ul Qoma, which have the faint whiff of East and West Germany about them, except they exist in the same physical space, rather than side by side. The wall dividing them is a psychological one, erected by an education system which teaches the citizens of one city to ‘unsee’ everything that happens in the other. Anybody who refuses to turn a blind eye is punished by a terrifying governmental body called The Breach. Obviously, this ends up being a problem for Inspector Tyador Borlú, who’s investigating the death of an exchange student with links to both places. Imagination is spread thick on every page of this story, which somehow manages to straddle sci-fi and 70s police procedural with aplomb.

The Crow Road by Iain Banks

(A Soupcon of Mystery)

How much crime does a book need to qualify as a crime novel? For me, The Crow Road sits exactly on the border. It doesn’t bother dusting off its mystery for the first third, and, even when it does, it’s left to simmer gently in the background, without any real urgency at all. At heart, this is the portrait of a Scottish family told over three generations, every chapter picking at the relationships tying it together and the secrets they go out of their way to avoid. Most of our story comes courtesy of university student Prentice, but there are flashbacks galore from other family members in other time periods. Over time these narrative strands combine, slowly revealing the mystery that’s poisoned this family for thirty years, forcing Prentice to get at the truth. Building a mystery this way is a very brave move on Bank’s part, but it works wonderfully.

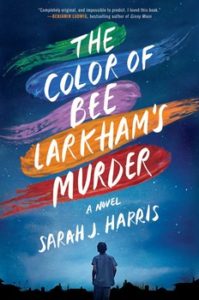

The Color of Bee Larkham’s Murder by Sarah J. Harris

(Mystery as Conduit to Alternative Psychology)

I love an unreliable narrator and one of the most original I’ve come across is thirteen-year-old Jasper Wishart, the protagonist of Sarah Harris’s excellent mystery novel. Jasper is face blind, so he can’t recognize people by their faces, only their voices. The poor kid also suffers from synesthesia, which means he interprets sounds as colors. Oh, and he’s convinced he’s responsible for the disappearance of his neighbor Bee Larkham, which might be true except his memories are a smear of colors and voices, making it impossible to tell. This story’s told exclusively from Jasper’s point of view, which means you’re often as lost as he is. Thankfully, his world’s as beautiful as paint splashed on canvas and Sarah Harris explores the intricacies of Jasper’s almost-alien mind with a great deal of tenderness.