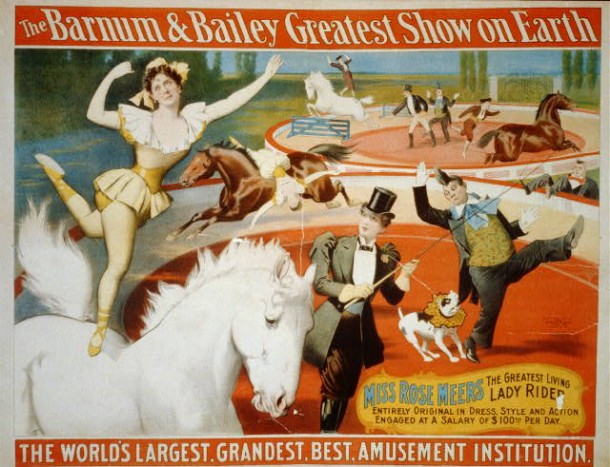

In truth, from the Golden Age of marvels onward, the honest acts and wonders of a circus, a carnival, a midway or a Ten-in-One were and are usually more astonishing than any birdseed and glue creation dreamed up by a down-on-her-luck manger or a dime museum owner looking to add just one more spectacular adjective to the long line before his name. Despite the exceptional talent, physical attributes or showmanship of performers billed as “freaks,” however, many outfits, from P.T. Barnum’s American Museum to today’s ragtag traveling carnival setup in the back parking lot of an empty strip mall, have resorted to the often expected tricks of the trade—the sideshow gaff and the bally fake. The con in plain sight.

Nothing struck the match of my imagination towards writing Miraculum—my new novel with a carnival setting—so much as HBO’s late, great television series Carnivale. In an episode of the first season, the carnival, desperate for business, puts on a “fireball” show rife with midway scams. One of them is the famous “Man Eating Chicken,” revealed behind the curtain to be a man, eating a chicken dinner. As Felix, the talker, tells the disgruntled marks with a sly wink: sure, you’ve been had. But what if you went back and told your friends to come on in and spend their nickel on a fake? Then you’d be in on the joke as well.

Whether they have a shot in hell of being believed or not, the absurdity behind sideshow cons means they deserves a tribute all their own. Whether these are the best or the worst, I couldn’t say. But they certainly are some of the most bizarre.

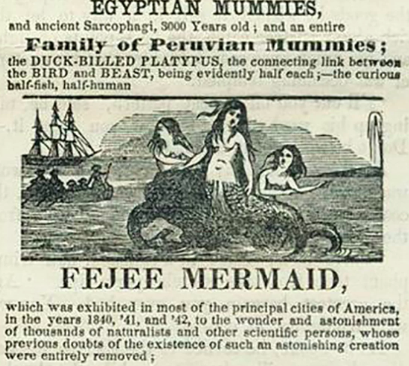

The Feejee Mermaid

Barnum’s “Feejee Mermaid” is probably the most well-known sideshow gaff and its history is inextricably linked with that of the American sideshow’s birth itself. The Mermaid was one of the first big attractions P.T. Barnum used to lure gawkers to his new American Museum, a dime joint of oddities operating in mid-nineteenth century Manhattan. Barnum’s museum was so popular—hooking tourists from across the country—that he eventually took his collection on the road, displaying it on the “side” of his big top circus tent. The spiel to go along with the Feejee Mermaid was typical: the mummified creature was said to have been caught off the coast of the Fiji Islands, proving that all of history’s myths were true. In reality, the Mermaid was nothing more than a macabre conglomeration of a monkey’s head and torso sewn onto the back end of a fish, with some added scales, hair and a pair of breasts tacked on for good measure. The result is a frightening creation—a prototype, perhaps, to the human centipede—but it served its purpose. It did fright, and delight, the uptight Victorian spectators who shelled out their dimes and came back for more.

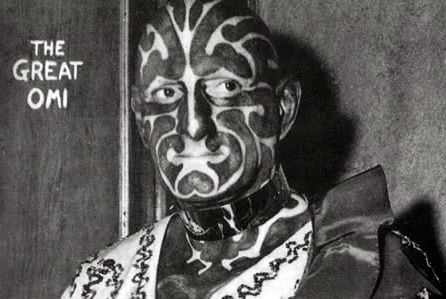

The Great Omi

Horace Ridler—aka “The Great Omi”—is another notorious sideshow fake, of sorts. I’m sure this point can be argued, since his head to foot tattooed zebra stripes were indeed real, but I love this story because it pushes the concept of the early twentieth century Tattooed Man or Lady to its limits. Ridler’s tattoos were authentic, but his story was not. To heighten his success, Omi, also known as “The Zebra Man” accompanied his body’s exhibition with a harrowing tale of being captured by savages in New Guinea and tattooed as a form of torture. When this wasn’t enough, Omi stretched his ears, pierced his nose, filed his teeth down to points and began wearing lipstick and nail polish. His wild story continued to evolve until his eventual death in 1969, marking over forty years of living, and profiting greatly by, an outrageous lie.

The Really Real Frog Band!

A lesser known gaff—but one that exemplifies the thousands of taxidermied animals kept behind the velvet curtain until the price was paid—is one of my favorites. The “Really Real Frog Band” was a collection of stuffed frogs, all posing with musical instruments, but all very much dead. When the rubes complained, the response was simple: they were real, they just weren’t alive. They had once played music, sure, but now they couldn’t. Why? They were dead. Not much to argue with there…

Giant Snake Eating Frog

Apparently frogs were easy to come by in the heydays of the sideshow world. While a typical animal gaff was simply to display one creature and call it another—a Capybara was the usual stand-in for a Live Giant Rat! for example—I love the cons that hinge on word play. Like the “Man Eating Chicken,” the “Snake Eating Frog” was just that: a snake large enough to eat a frog. Never mind the bally banner depicting a massive toad with a snake tail between its lips. It was the headline, not the illustration, that counted.

Circassian Beauties

Along the same lines of the Great Omi’s deception is that of Barnum’s famous Circassian Beauties. Their hair was real—P.T. Barnum’s “harem” of beautiful women washed their hair in beer and teased it dry to create a moss-like halo around their heads—but their background was anything but. Barnum claimed the Beauties were the very same fabled women from the Russian mountains whose sex appeal had been legendary since the Middle Ages. Naturally, they had also been sex slaves and concubines, skilled in the Far-Eastern secret mysteries of love and pleasure, and only recently escaped to civilization. In reality, the women were as American as could be, often poor, but pretty girls who were looking to break into show business. Oddly, true Circassian Beauties were known for their long, tamed locks so why Barnum had his girls wear such a bizarre hairstyle is a mystery.

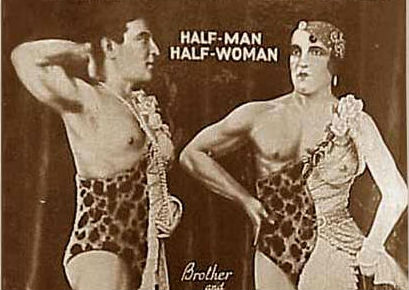

Albert-Alberta

From the 1920s through to the 1960s, Half-and-Half acts were all the rage on the midway and Albert-Alberta is merely one example among hundreds. Billed as hermaphrodites, “He-She”s were simply very talented drag queens who drew a line down the middle of their bodies. Albert-Alberta exercised one half of his body and let it grow hairy, while he shaved and pampered the rest. He wore a boot on his right foot, a dainty high-heeled shoe on the left. A mustache on one side of his face, lipstick and rouge on the other. And, of course, he had one breast—a sack filled with birdseed if anyone had bothered to take a closer look. I particularly admire Harry Caro’s dedication, as he kept to his split-identity off the bally as well. Describing himself as a “disappointment” to both opposite sexes, he swore never to marry and devoted himself to raising Pomeranians when he wasn’t parading across the sideshow stage.

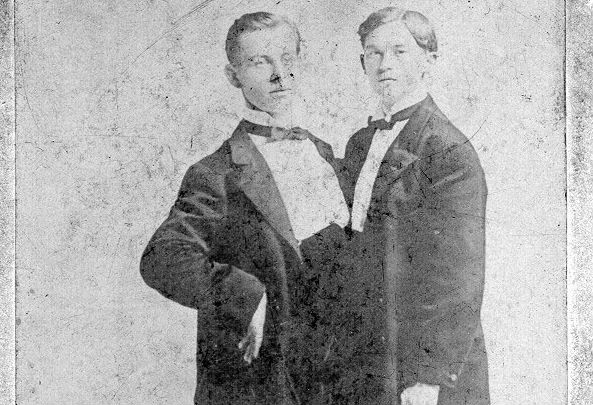

Adolph and Rudolph

Finally, we come to my favorite “rigged” sideshow con—Adolph and Rudolph, a pair of fake Siamese twins. Rudolph was born with small, malformed legs he could have cashed in on, but Siamese twins were the hotter commodity in the late 1800s and with a little creative handiwork, Rudolph was soon hitched onto the side of his partner Adolph and the Austrians began their act. The harness both men wore under their suits kept Rudolph in place on Adolph’s hip and, from photographs at least, the look is quite convincing. At least they never embarrassed themselves by, quite actually, falling out with one another on the stage. That honor goes to the Milton Sisters, a gaffed Siamese twin act who ruined their reputation by fighting during a performance, cutting their shared dress down the middle and storming off in opposite directions.

***

Despite the above examples, and the prevalence of many, many others in the almost two hundred years of sideshow history in America, the majority of “freaks” found on the bally and behind the curtain were genuine. Often, spectators fell for the gaffs, but were suspicious of the true acts. The actual marvels were almost too real to be real, but the rubes paid their dimes nonetheless. After all, we don’t go to the carnival seeking the truth—we go there to “ooh” and “ahh.” To let go of reality for a few hours. To let ourselves be surprised. The “show” in “sideshow” is all that really matters.