“It is impossible to drive anywhere in America today without encountering a patient, droop-shouldered chap who stands by the roadside and continuously jerks his thumb across his chest. He is the hitch-hiker, one of the strangest products of the auto age, and he is getting to be a prominent part of the American landscape. He is also getting to be an intense pain in the neck. Just why it should be considered proper for a man to stand by the roadside and beg free transportation from total strangers is a mystery….But the hitch-hiker is something more than a nuisance. There are times and places when the hitch-hiker is an actual menace to public safety….[M]urders of motorists by hitch-hikers have been recorded recently in Oregon, Virginia, Nebraska, New Mexico, and Oklahoma….It might also be remembered that when Pretty Boy Floyd was finally hunted down and killed in Ohio he was in the process of hitch-hiking across the country….As an individual, the hitch-hiker may be a likeable chap. As an institution, he is getting to be pretty trying. One wonders just how much longer the American motorist will put up with him.”

—“Hitch-Hiker is Menace and Nuisance,” Santa Rosa Republican (September 11, 1935)

___________________________________

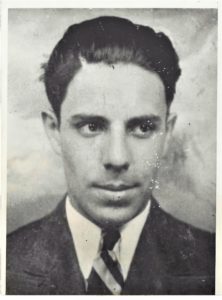

On the afternoon of Monday, February 5, 1940, a handsome, narrow-faced, dark-eyed youth with a mane of black hair calmly walked into the police station at Las Vegas, Nevada, then a small city of some 8500 souls, placed a revolver on a table and quietly implored, “Lock me up. I’ve just killed a man.” Asked to explain himself, he added “I guess I’m just a smart hitchhiker. I killed him to get some money.” Upon examining the car which the darkly attractive young man had driven into the city, the police found blood spattered over the seat and floorboards and an empty gun cartridge on the floor. The self-described “smart hitchhiker,” who gave his name as George Emanuel, his native state as Indiana and his age as twenty-three, guided police some thirty miles southwest of Las Vegas, to the turnoff to the small town of Goodsprings. There by the side of the road the police found the body of a man who bore a fatal gunshot wound to the head and whose clothes had been riffled, presumably for cash.

George Emanuel

George Emanuel

Earlier that day the murdered man, stocky, forty-two year old Floyd Monroe Brumbaugh, had picked up the hitchhiking George Emanuel in the town of Barstow, California, offering to take him to Las Vegas. According to George’s account, the two men had ridden peaceably from Barstow across the California-Nevada state line, “talking of this and that,” until, some thirty miles from Las Vegas, the younger man suddenly pulled a gun from his pocket and shot his benefactor point blank in the head, killing him instantly. “He never saw it coming,” George told the police. “He was looking straight ahead and never knew what hit him.” Brumbaugh, who had been driving at around fifty-five miles per hour when George fired the fatal shot, slumped down over the steering wheel, causing the car to swerve, but his frantic murderer was able to shove his bloody, brain-spattered corpse aside and gain control of the careening machine. After taking the turnoff to Goodsprings, George pulled over and dumped Brumbaugh’s body out by the side of the road, going through his pockets for cash and finding but a single penny. (In his haste he missed the $6.50—about $118 dollars today—which Brumbaugh had carried on his person.) Demoralized, George dazedly drove into Las Vegas, where he gave himself up to local authorities, insisting that robbery had been his sole motive for the shocking slaying. Soon sensation-hungry newspapers across the country were emblazoning news of Nevada’s ironic “one-cent hitchhiker slaying,” doubtlessly spurred on by the murderer’s dark good looks and spotless social standing.

A pulchritudinous scion of highly respectable small-town, white-bread Middle America, George Hawley Emanuel claimed among his distinguished forebears not only a prominent Indiana doctor and lawyer but his beloved paternal grandmother, Ida Virginia Emanuel, head librarian of Auburn, Indiana’s Eckhart Public Library until her death in 1923. George’s identically named late father, who died when young George was only sixteen, had been a Chicago journalist and publicity agent while his widowed mother, Irene, was employed as the executive secretary to the Family Welfare Association of Evansville, Indiana—the Emanuel family, which also included George’s younger brother and sister, John and Mary, having moved from Chicago to Evansville four years earlier.

Young George had graduated with honors from Evansville High School and attended Howell Military Academy when he married welfare worker Marjorie McKinnon, relocating with her to Indianapolis. The couple divorced in 1939 and a despondent George returned home to live with his mother, clerking in a bookstore and working around the house until October, when he resolved, like many another restless soul during the unsettled years of the Depression, to hitch his way to the Golden State of California. His avowed plan was to visit his brother John, a student at Stanford University, and a couple of aunts. Once in California he became a laborer with the North American Airplane Factory in Inglewood, near Los Angeles, where the advent of the Second World War had already started a boom in the munitions industry. However, during the first weekend of February 1940 George, having abruptly quit his factory job, started drinking heavily and lost a large sum of money at the racetrack at Santa Anita Park in the city of Arcadia. On Sunday he determined to pick up such meagre stakes as he had in the Golden State and hitchhike to New Orleans, first purloining and loading the gun owned by one of his roommates. In Los Angles a friendly man picked him up in his car and carried him some eighty miles, dropping him off near Victorville, where another obliging fellow spotted him and drove him an additional forty miles to Barstow, cite of his fatal encounter with Floyd Brumbaugh.

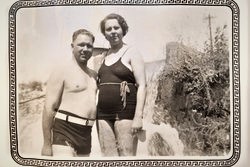

Floyd Brumbaugh and Willie Bell Brumbraugh

Floyd Brumbaugh and Willie Bell Brumbraugh

The late Floyd Brumbaugh was also originally a native of the Hoosier state, although he hailed from the far northern town of Goshen, located all the way across the state from George’s Evansville. An itinerant carpenter of substantially German descent, Brumbaugh in June 1939 had departed Goshen for California, stopping off for the time at the town of Tulare, located in the heart of the San Joaquin valley. Like George the ruddy-faced, barrel-chested, 5’7” Brumbaugh seems to have led a peripatetic life and had a history of erratic relationships with independent women prior to his death in the Nevada desert. During the First World War, when he like George was but a youth, he had served with the United States military at the U. S.-Mexican border town of Nogales, Arizona, site in 1918 of the so-called Battle of Ambos Nogales, a violent border clash between Americans and Mexicans. In 1919 he left the army and married Arizona schoolteacher Emma Casanega, a daughter of Thomas David Casanega, a former Arizona deputy sheriff, saloon keeper and cattleman originally born Tomo Vido Kazanegra in the European principality of Montenegro. With Emma Brumbaugh fathered two boys and a girl, but the couple divorced in 1930 and the children all remained with their mother. Brumbaugh moved five hundred miles away to Carlsbad, New Mexico, found work as a potash miner and wed double divorcee Willie Belle Nicholson, proprietress of the Crawford Beauty Clinic; yet, although the couple had remained married at Brumbaugh’s death, Brumbaugh was living with his parents in Goshen when he decided to make his fateful foray out to California in June 1939. It was believed that when he picked up George Emanuel in February 1940, Brumbaugh planned to return home to Goshen, after making a stop at Carlsbad to visit his wife, whom he had seen only once in three years. Both he and George were men at loose ends, but George’s loose ends were burning.

Although “one-cent slayer” George Emanuel damningly had confessed to Brumbaugh’s brutal murder and taken the Las Vegas police out to the exact spot where his victim’s body was located, he later recanted his confession and pled not guilty, presumably on account of Nevada courts at that time not allowing an insanity plea. However, at his trial in early April for first degree murder the handsome youth, as he was often sympathetically described in newspapers, broke down on the stand and confessed (yet again), sobbing “I don’t know why I killed him….I didn’t intend to rob him….It just seemed the thing to do at the time. I couldn’t help myself, I guess….I had hoped that it might be just a bad dream.” Some of the spectators in the packed Las Vegas courtroom were moved to tears by George’s testimony, and there were further displays of waterworks when George’s mother Irene testified. Irene Emanuel insisted that her boy had been “the most pacific sort of lad when he was small” and that he since had led an exemplary life, aside from his recent spot of murder. She speculated that some sort of mental derangement had set in after the failure of his brief marriage, tearfully avowing that she should have seen that he received psychiatric assistance at the time.

In his closing argument the prosecutor, Clark County district attorney Roland H. Wiley (best known today as the idiosyncratic creator of the Cathedral Canyon, a onetime popular shrine erected fifty miles outside of Las Vegas), mercifully allowed to the jury of ten men and two women that he would be satisfied with sentencing the youthful defendant to life in prison, rather than putting him to death in the gas chamber. “Extinction is not necessary,” he benevolently pronounced. “But redemption is possible.” The jury thereby followed suit, rendering a verdict of guilty but recommending a punishment of life imprisonment, which the presiding judge accepted, to the palpable relief of George’s attendant mother, brother and aunts. Newspapers made no mention of any of Brumbaugh’s kin having attended the trial. Astonishingly, Willie Belle Brumbaugh only received official confirmation of her husband’s February death a week after the murder trial had concluded in April.

***

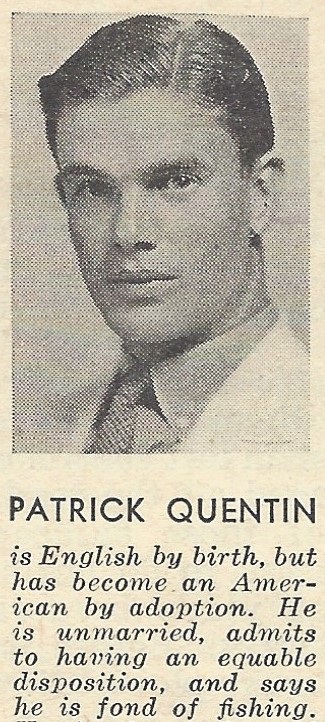

Three-and-a-half years after Nevada’s infamous “one-cent hitchhiker slaying,” authors Richard “Rickie” Wilson Webb and Hugh Callingham Wheeler, who wrote popular crime fiction together as Q. Patrick, Jonathan Stagge and Patrick Quentin, were out of the Army and back in each other’s company again, spinning writing ideas and otherwise killing time at the Riverside Hotel in Reno while awaiting the six-week statutory period for the granting of Webb’s divorce, after six tumultuous months of a most ill-advised marriage, from his wife Frances Winwar, a successful author whose recent books included biographies of Oscar Wilde and Walt Whitman. Quite possibly old accounts of George Emanuel’s Las Vegas murder trial with their hints, to those so inclined to hear it, of homosexual innuendo, and the prominently displayed newspaper snapshot of the photogenic young killer, who resembled nothing more than a dazzling movie star gangster, caught the authors’ eyes, just as the Leopold-Loeb case had fascinated Rickie Webb years earlier, inspiring him to write his highly regarded 1935 Q. Patrick detective novel The Grindle Nightmare.

Rickie Webb’s and Hugh Wheeler’s fifth Patrick Quentin novel, Puzzle for Fiends, published three years after the authors’ ’43 Reno sojourn, opens with a brief prologue wherein their series characters Peter and Iris Duluth are sadly saying goodbye to each other at the Hollywood Burbank Airport. Peter finally has been discharged from naval service in the Pacific and has returned home for good—only to find that his glamorous actress wife Iris is patriotically heading out to the Pacific on a three-month USO tour. Iris is forlorn at having to part ways yet again with Peter, but the now ex-seaman puts on a show of conversational bravado, telling her to “think of the Occupation Army panting to see its favorite Hollywood cookie in the flesh.” After retorting “I don’t want to be seen in the flesh except by you,” Iris bids him to be careful on his drive down to Naval Base San Diego, for his “last fling” with the boys from the boat. “All that champagne we drank at the hotel,” she worries. “You know what champagne does to you.” Shrugging off such wifely concerns, the lonely Peter heads back to his car. As he opens the door, he feels a hand on his arm and turns around to see a “boy with a thin, narrow face, close-set eyes and an untidy mane of black hair.” It seems this “boy” wants to hitch a ride to San Diego and Peter, the champagne having made him “expansive,” readily assents, as he catches a glimpse of Iris’ plane zooming down the runway. End prologue.

Many bizarre and horrific events follow over the course of this crime novel, which is highly recommended, but what is of further pertinence to us here is its epilogue. Therein Peter Duluth, suffering from amnesia and having barely escaped with his life a week earlier from the nefarious clutches of some exceedingly fiendish individuals, is now residing at a “cheap little Los Angeles hotel,” still unable to remember who he really is, his future looking “as blank and featureless as a drowned man’s face.” He glumly sits down “in one of the lobby’s worn leather chairs,” and looks at the front page of a newspaper:

The photograph of a man at the head of a column of print caught my eye. Wasn’t there something dimly familiar about that young, narrow face with the close-set eyes and the flopping mane of black hair?

Indeed there is. The dark young man in the newspaper photo is none other than Peter’s bold hitcher, one Louis Crivelli:

[Crivelli] had been arrested in San Diego for a car holdup and, under police questioning, had admitted to having bummed a ride from a certain Peter Duluth, slugged him and stolen his car one month before….The police were going to take Crivelli to the spot where he claimed to have abandoned Mr. Duluth and were going to start a new search from there. It was believed now that Mr. Duluth was suffering amnesia caused by a blow on the head struck by Crivelli.

Turning to the continuation of the article on page three, Peter finds himself staring at a picture of “Peter Duluth,” whom he realizes is none other than himself. Everything comes back and he goes over to the phone booth “in a dreary corner of the lobby” and calls his ministering angel Iris, who on having heard of his having gone missing rushed back home from Japan….Aside from the Italianization of the hitching villain’s name from George Emanuel to Louis Crivelli (“Emanuel” often is associated with Jews, but it also is a Welsh protestant surname) and the fact that Peter mercifully is sapped by Crivelli rather than shot, the similarity between the real life crime on the road to Las Vegas and the fictional one on the way to San Diego seems sufficiently clear.

If Rickie Webb and Hugh Wheeler followed other Nevada news as well, they would have found that violent sudden death seemed to plague that far southern section of the state like it was an arid but no less unhealthful version of the Bermuda Triangle. On the evening of January 16, 1942 a Burbank bound plane carrying a real life Hollywood actress, Carole Lombard (who was returning to LA from a patriotic war bond rally in her home state of Indiana), along with twenty-one other people, including Lombard’s mother and press agent, three crew members and fifteen U. S. Army Air Corps personnel, slammed into Potosi Mountain, a dozen miles from Goodsprings, instantly killing everyone on board. At the Pioneer Saloon in Goodsprings Lombard’s husband, actor Clark Gable, for three days futilely waited for hopeful news of his wife’s fate. Not for him the happy fictional reunion of Peter Duluth with his beloved actress spouse.

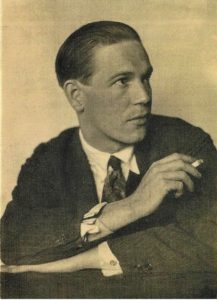

Rickie Webb

Rickie Webb

Sixteen years later, on April 21, 1958, there occurred another Nevada air disaster, the worst in the state’s history, when southwest of Las Vegas, not far from the spot where George Emanuel had dumped Floyd Brumbaugh’s body, a Douglas DC-7 transport aircraft carrying forty-two passengers and five crew collided with a U. S. Air Force fighter jet crewed by two pilots. Both planes fell nearly vertically to the ground and exploded on impact, leaving no survivors. Among the dead passengers of the Douglas DC-7 was a forty-year-old Douglas Aircraft executive from the Los Angeles area named John Barrett Emanuel—the younger brother of George Emanuel, who had been in attendance in Las Vegas on that April day eighteen years earlier when, due the beneficent indulgence of the jury, judge and prosecutor, his murderer brother had avoided being put to death in the gas chamber for the commission of first degree murder. Less than a month later, the Emanuel boys’ ailing mother Irene died at the age of seventy in Sacramento, California, where she lived with her daughter. Irene Emanuel had departed from Evansville, Indiana two years after her elder son’s trial to become an executive secretary with the California Red Cross. The civic-minded widow was also active in the California League of Women Voters.

Also civic minded, in his later years, was George Emanuel. When he died in 1995 from a heart attack at Ventura, California at the age of seventy-nine, he was lauded as a longtime supporter of youth baseball. Back in 1958, the year of his brother’s and mother’s death, George, then a free forty-one year old sheet metal worker, had started a Little League baseball team in Inglewood, the city he had so hastily exited with a loaded gun in 1940, so that his young son could play the sport. Besides his son—who at his father’s death lived in Victorville, where George had once infamously hitched a ride—the dead man left a widow, two daughters, eight grandchildren and eleven great-grandchildren. Seemingly life ended pacifically for elderly family man George Emanuel. Before his own death, however, was George ever plagued by thoughts of his wanton crime from long ago? Had he ever come genuinely to understand why he even committed it? Was robbery really his motive or had some other reason which he could never bring himself to name—a desire to make a Leopold-Loeb style thrill kill or an attack of so-called “gay panic”—prompted the killing? I would have given more than a penny—inflation adjusted, of course—for the one-cent slayer’s thoughts.