As the marshals’ search for the Commander sputtered during the first months of 2012, there was no way for them to know that the key to solving this mystery sat in a drawer of a metal filing cabinet at the New Mexico State Library in Santa Fe. Had Bill Boldin and his team known where to look, they could have found, alongside back issues of the Ruidoso News, the Carlsbad Current-Argus, and the Bernalillo Times, a blue-and-white box containing microfilmed issues of the Gallup Independent from July and August 1997.

As it had for more than three decades, the masthead on the August 8 edition of the local newspaper proclaimed that, inside, readers would find “The Truth Well Told.” Offering home delivery to most of the Navajo, Zuni, and Hopi Reservations, the Independent contained a wealth of news about the tribal communities that made up a good part of its readership. The front page that particular Friday featured an article about a probe into alleged corruption by the Navajo Nation’s president, while, on the next page, an unrelated photograph showed a Navajo council delegate named Alfred L. Yazzie, a man whose unusual surname, derived from the Navajo word for “little,” was common in these parts. Of course, not everyone bought the newspaper for the news. Readers planning a visit to Gallup’s annual powwow found a schedule listing start times for six days of Indian ceremonial dances, Indian rodeos, and Indian art marketplaces. Other, more industrious readers who planned to spend the coming weekend job hunting found numerous possibilities listed in the help-wanted section on the paper’s second to last page. The open positions advertised that day included a silversmith at Pow Wow Indian Jewelry, a Navajo-speaking teacher at the Cuba Independent School District, and a listing for thirty-five hazmat security officers at a company called Totem Security.

There was little that separated Totem Security’s solicitation, which appears to have run only that day and the next, from those surrounding it on the page. In the truncated language of the classified job ad, the company said it sought healthy candidates with a GED, a valid driver’s license, no felony convictions, and a willingness to consent to a full background check. Claiming it would provide full training to the right applicant, Totem offered annual pay of up to $50,000, along with medical and dental insurance, two weeks’ paid vacation, and a 401(k) retirement plan. In a town where the per capita annual income hovered just below $18,000, it was a compensation package certain to attract attention, and interested parties were asked to call a number in Portland, Oregon, for more information.

There was little that separated Totem Security’s solicitation, which appears to have run only that day and the next, from those surrounding it on the page. In the truncated language of the classified job ad, the company said it sought healthy candidates with a GED, a valid driver’s license, no felony convictions, and a willingness to consent to a full background check. Claiming it would provide full training to the right applicant, Totem offered annual pay of up to $50,000, along with medical and dental insurance, two weeks’ paid vacation, and a 401(k) retirement plan. In a town where the per capita annual income hovered just below $18,000, it was a compensation package certain to attract attention, and interested parties were asked to call a number in Portland, Oregon, for more information.

Less than a week after the ad appeared in the Independent, completed applications began to flow from the newspaper’s circulation zone to an address in Northeast Portland, just across the Columbia River and the border with Washington State. They came almost entirely from Gallup and other nearby places with faraway-sounding names like Zuni, Gamerco, Mexican Springs, Sheep Springs, Thoreau, and Crownpoint in New Mexico and Saint Michaels, Window Rock, and Fort Defiance in Arizona. Once completed, the employment applications, which also served as background check forms, contained an applicant’s name, address, telephone number, date and place of birth, social security number, driver’s license number, educational history, criminal convictions, passport status, and parents’ names. It was a lot of information to send off to an unknown company, but the fine print said it would be used to process the requisite background check for a security job that sounded like it was being offered only to the most trustworthy individuals. If job seekers needed additional assurance that this was all on the up-and-up, the form guaranteed them that “the information provided is confidential between myself, the Company and its agents.”

If potential applicants still had doubts, they could check and see that Totem Security had filed articles of incorporation at the Oregon secretary of state’s office in Salem. Printed on a do-it-yourself form produced by Self-Counsel Press in Bellingham, Washington, the two-page document gave the same Portland address that was on the company’s job application and listed the company’s registered agent and sole incorporator as one Bob Redbear. It was a name, like Totem Security, that seemed tailor-made to engender trust among the Native American applicants likely to read the company’s ad when it ran in the paper that weekend in August. But something wasn’t quite right. While the job hunters who sent applications to Portland would eventually go on to work at a construction company, a tribal water agency, an Indian hospital, a school district, and a Gallup liquor store called The Tropics, not one of them ever landed one of the lucrative hazmat positions advertised by Totem Security. In fact, Totem Security existed nowhere but in the corporate listings of the State of Oregon and in the imagination of the man who had composed the ad in the Independent. The address listed on the company’s applications was a mail drop at a Portland store known to forward letters and packages to its snowbird customers all across the country. The company’s articles of incorporation had been filed just eight days before the ad first appeared in the Gallup Independent as a back-stop in case anyone went to check its bona fides. Bob Redbear was an alias for a man the applicants never met. And the bogus security company and its carefully targeted help-wanted ad were just parts of a scheme this man had concocted to harvest a thick file of vital information that he could tap for a variety of purposes over the next fourteen years. Soon this man would reinvent himself as Commander Bobby Thompson.

The Commander had just turned fifty. The personal data he stole using his wanted ad in August 1997 was a perverse birthday gift he gave himself to prepare for a new life. In many ways it was also the seminal moment of the Navy Veterans scam, for he would use his bounty of names, birth dates, and social security numbers to create various identity cards to collect money, launder it, and, finally, mount his escape when the authorities closed in. Exactly how he did all this was a story spelled out in a trail of paper at government offices across the country and hinted at in an underground criminal bible that, like Totem Security, had, by 2010, been all but forgotten.

There were dozens of ways the Commander might have perfected his skills as an identity thief. One possibility was that he learned it in a book by Barry Reid. A one-time law school student, Reid’s legal career was cut short by a marijuana-smuggling conviction that landed him at Terminal Island, a low-security federal prison near Los Angeles that he later described as “a sort of criminal Harvard.” An enterprising young man, Reid took the knowledge he gained at this lesser-known Ivy and launched Eden Press, a publishing company that cranked out short, detailed manuals, dubbed “books for crooks,” whose titles included Classic Mail Frauds, How to Beat the Bill Collector, and Short Cons. Reid’s company was best known, however, as the publisher of The Paper Trip. This short paperback volume rose to such notoriety that in the mid-1970s it helped prompt a 781-page Department of Justice report titled The Criminal Use of False Identification. According to this government publication, fake identities were a criminal’s best friend, tools by which denizens of the dark could “appear and disappear at will by creating fictitious ‘paper people.’” The Paper Trip, some said, was the “underground textbook of phony ID that has become a counterculture bestseller.”

Filled with quotes from John Steinbeck, William Shakespeare, Lao-tzu, and the Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus, the tone of The Paper Trip wavered between a straight-ahead how-to manual and a libertarian philosophical treatise that reminded Americans that they had a god-given right to go by whatever name they damn-well pleased. “Ever since the early days when the first Americans—the Indians—used the device of name-change to denote accomplishment (sort of like a tribal “promotion”), Americans have changed their names in order to gain some form of success and/or acceptance,” the author wrote. “What some people do not realize, however, is that the custom did not die with the closing of the frontier—and, in fact, is still flourishing today.” To ensure its readers could take part in this most American of pastimes, the book urged them to prepare and practice for the day of their escape. “Prior conditioning can seriously inhibit your ‘transformation,’” read one section of the manual. “No matter how much you long for a new identity, the comfortable familiarity of your original name can make you very uneasy about introducing yourself in your new ‘incarnation.’” To get over this uneasiness, the booklet urged readers to practice saying their assumed name out loud and writing out their adopted signature before the time to disappear actually arrived. “Like a chameleon, a Paper Tripper’s self-preservation depends upon his ability to blend harmoniously into his chosen environment,” read one section that was illustrated with a pen-and-ink drawing of dozens of identical businessmen. The main objective, it emphasized, was “to disappear into the crowd, to become inconspicuous.”

To do so The Paper Trip favored real identities obtained in someone else’s name over forgeries, and it outlined a technique for obtaining them. While Reid referred to this method as the “Birth Certificate Route,” law enforcement called it the “Infant Death Identity process.” This method involved obtaining a real birth certificate in a dead child’s name and using it as the “breeder document” with which one could then obtain a social security card, a state ID, credit cards, and, eventually, an entire new persona. Readers were instructed to first identify a deceased individual with their same approximate birth date, sex, and race who died as a child “long before he got entangled in the paper morass you’re now trying to escape.” Potential names could be found by wandering through a cemetery, jotting down info from gravestones, or, more simply, by visiting a library with a good supply of microfilmed newspapers. There, readers were told to search editions from the years in which they themselves were children, looking for articles or obituaries about the recent death of a kid who, if now living, would have an age that was close to their own. Preferably, they would find a child who had died in a tragic accident. “Excellent possibilities,” the book noted in one of its more macabre moments, “would be those in which an entire family was wiped out, as there would be little remembered of them by now.” With a name in hand, the next step involved requesting a certified copy of the dead child’s birth certificate, a request one could make in writing by posing as the now-grown child or as his potential employer conducting a background check. Once the document was received, the tripper was on the path to a new name and all the freedom it promised. “With a ‘certified’ copy of a birth certificate, issued by some agency of state or local government, it is relatively easy to apply for and receive virtually any form of id desired,” Reid instructed. According to The Paper Trip, the rest was up to the reader who adopted Reid’s advice. “You are the new person, and never doubt it!” the book read. “If you don’t, no one else will, either! Ask yourself, who else would you be if you weren’t ‘you’? no one but who you say you are, that’s who!! Why, you can even prove it: ‘Certainly, just check my ID.’”

Whether or not he ever read the book, these were words the Commander lived by. Like any good con artist, he knew that most people he met, whether it was in a bar or in a government office, did not go through each of life’s million tiny transactions wondering if the person on the other end was trying to deceive them. He knew that most people believed what they were told or what they read on a piece of paper. With the confidence this understanding gave him, he fully inhabited the many identities he created over the years, becoming comfortable enough to slap assumed names all over state and federal forms, even audaciously using one such stolen identity to shake hands with the president of the United States on multiple occasions. As he once told his lawyer, “life is argument.” For him this ethos trickled down even to the name he called himself. I am who I say I am. Who else would I be if I wasn’t me? No one but who I say I am, that’s who. And while he would call himself by many names over the years, the way in which he created these identities evolved with the times.

At first, the Commander may have used names stolen from young boys who died when the con artist was himself just a child. There was Michael Hannon, an academic standout who died in 1960, at just nine years of age after suffering through a short illness. Then there was Gary Hixon, who drowned in a California pool in 1962 while traveling with his family to the World’s Fair in Seattle. Both boys were from Colorado, and in the years preceding the Navy Veterans Association scam, the Commander appeared to have used both their identities. Presumably, he had done so in the manner outlined in The Paper Trip—first obtaining their birth certificates and using them as breeder documents. But this way of creating an ID was not foolproof. It depended on a loop-hole, and loopholes could be closed.

For years paper trippers borrowing names like Hannon and Hixon took advantage of a system in which birth and death certificates were kept as completely separate records. But the 1976 Department of Justice report, partially prompted by The Paper Trip, made some suggestions. In addition to recommending passage of tighter laws and adoption of more stringent procedures for birth certificate applications, the commission suggested the creation of a new system that would cross-reference birth and death records so that the word “deceased” might be marked on copies of birth certificates belonging to people who had departed the earthly plane. Doing so would, in effect, make it impossible for a would-be ID thief to present a dead child’s birth certificate as the foundational document on which to build a new life. If they were already deceased, there would be no reason they would be applying for an ID card, after all. The Paper Trip warned that this new era of cross-referencing was coming and that computers would hasten its arrival. But, not to be discouraged, its author offered some backup plans. Among these was the use of vital information taken not from the dead but from the living. Appearing to have previously used the names of long-gone children, by 1997 the Commander himself had pivoted to the live-victim method. He was wildly successful in capturing a slew of identities with the Totem Security applicants in Gallup, specifically tailoring the language and placement of his help-wanted ad to ensnare the perfect victims.

As Bill Boldin had discovered on his trip west, the Commander had gone after a group of people almost as unlikely to raise an alarm as dead kids—live Indians. Not a single one of the Totem Security applicants was known to have ever reported that their name had been stolen or put to use. There was a likely reason why. “Well, us Navajos, we don’t check our credits,” said Richard L. Overturf, a Totem Security applicant who, by 2014, lived so far from civilization that, instead of a street number, his driver’s license listed his address as the number of miles one had to drive from a tiny highway junction to pay him a visit. Overturf had associate’s degrees in liberal arts and Diné, or Navajo, studies, a pedigree that made him one of the better-educated men whose names were among the sixteen Totem Security applications still known to exist in 2020. Most of the others were from high school graduates or ID recipients, one of whom would later freely admit, “I can barely turn a computer on.” Many of these job seekers were Native Americans, coming from the Navajo Nation, the Zuni Pueblo, and the Crow Tribe in Montana. Years later not a single one could remember reading the Totem Security ad in the Independent or filling out an application, but most said that the personal data was deadly accurate, and it was, for sure, their handwriting on the employment form. The year “1997, that was a while back,” Albert Gros-Ventre said when asked nearly twenty years later whether he knew how an application containing his information ended up in the Commander’s hands. “I’m guessing that it was probably at a job fair that was just hand carried to a receptionist. I’m not too sure.”

Like Gros-Ventre’s, many of the Totem applications that are still around came from men with memorable surnames like Bitsie, Booqua, Khweis, Mariano, Simplicio, and Yazzie. These were not easily forgettable names, like Smith or Jones, that a fugitive might hope to use to easily blend in before being forgotten altogether. These were second-tier names the Commander stockpiled as an emergency stash to be used only when better options had been exploited and burned through.

Four months after the hazmat security ad first appeared in the Independent, the Commander was in Indiana, where he put to use two of these better options: Elmer L. Dosier and Isaac N. Frazier. Though neither man’s Totem Security application was ever found and though it cannot be reported with absolute certainty that they even filled them out, both men lived in and around Gallup, making it likely that, along with many of their neighbors, they had inadvertently fallen victim to the identity-theft scheme in the summer of 1997. While little is known of how the transaction took place, on December 17 the Commander entered a branch of Indiana’s Bureau of Motor Vehicles in Indianapolis and obtained a state ID card in Dosier’s name. The next day he made another trip to a BMV office, this time carrying a copy of Frazier’s Louisiana birth certificate issued one month earlier. The man he pretended to be that day—Frazier—was, in actuality, an air force veteran born in New Orleans in August 1948, almost exactly one year after the Commander’s real birth, in a city nearly 1,200 miles to the northeast. Though their birth dates closely aligned, not all their vital statistics did. Unlike the Commander, the real Frazier was an African American and a long-time member of the NAACP. Perhaps hoping that the winter holiday season would leave the clerks working at the bureau that day distracted, the Commander waited his turn and presented Frazier’s birth certificate and an application for a state ID card in his name. Though this card would not allow him to drive as a license would, he seemed to prefer this type of ID. As The Paper Trip had advised, state identity cards were quicker and easier to obtain. The trip to the BMV proved to be a success, and soon the Commander had two Indiana ID cards bearing his picture under the names of both Dosier and Frazier.

Six months later, in June 1998, he strolled into a similar office, this time in his new home state of Florida, and obtained a third identity card, using the name of yet another man who had lived in the Southwest in the late 1990s: a Choctaw named Bobby Charles Thompson. It was in Indiana, however, that the con artist felt most at ease when obtaining ID cards. In January 2000 he returned to Indianapolis and got an ID in the name of a fourth likely Totem applicant, Gallup resident Ronnie Brittain. Perhaps he chose Indiana, the so-called crossroads of America, because it was smackdab in the middle of the country. Or perhaps it was because he had discovered it was an easy place to get what he needed. In 2004 the Indianapolis Star reported that problems at the state’s fraud- and corruption-plagued Bureau of Motor Vehicles had allowed “hundreds, if not thousands, of foreign nationals to obtain driver’s licenses and state identification cards illegally.” That same year news reports also revealed that in Marion County, home to Indianapolis, 10 percent of the state’s BMV employees had criminal records, half of which were for crimes involving theft or deception. This was the kind of bureaucratic corruption and incompetence a man like the Commander knew how to find and exploit, something he did on multiple trips to the city over the course of a decade. Between 1997 and 2008 he would obtain at least nine ID cards under four different names from the Indiana BMV. These trips of reinvention were well-planned affairs.

Between 1997 and 2008 he would obtain at least nine ID cards under four different names from the Indiana BMV. These trips of reinvention were well-planned affairs.In April 2002, months before he first applied to the IRS for tax-exempt status for the Navy Veterans Association, the Commander strolled into an Indiana BMV office with a thick beard and dark shirt and renewed the ID card he had received five years earlier in the name of deceased cop and former New Mexico resident Elmer L. Dosier. That very same day, after shaving his beard down to a handlebar moustache and changing into a white shirt, he again entered a BMV branch and renewed his Isaac Frazier ID card. In addition to making sure each name he assumed had its own look, he also took steps to ensure that he maintained that appearance across years when he went to renew an old ID card. For instance, when he first got a Ronnie Brittain ID card in 2000, he wore a wispy haircut, dark reading glasses, and a moustache that grew down his face into a hint of a goatee. When he returned five years later to renew the card, he was a bit grayer, but his moustache, haircut, and glasses remained the same. In case anyone at the BMV was paying attention, they would have seen that Ronnie Brittain might have aged and put on a few pounds, but, clearly, he still looked like the same guy.

Making sure that the photos on his ID cards looked just right required meticulous planning. It would later be revealed that the Commander traveled with eight pairs of wire-rimmed and plastic glasses; a beard trimmer; various hair clips, combs, and shears; Maybelline Great Lash mascara; a tube of Clubman moustache wax; and a plastic container of what appeared to be gray hair chalk. Though deeply planned affairs, these trips were still just a means to an end, journeys to get identities that would serve some larger purpose in his complex fraud. Some helped him perpetrate his crime. Others helped him escape from it.

In 2005, for instance, five months after going to Indianapolis to renew his Ronnie Brittain ID card, the Commander was back in Florida finalizing his initial agreement with the company that would become his main telemarketer, Associated Community Services. That July he passed through the oversized arch doorway at a branch of the First Commercial Bank of Tampa Bay that sat on a six-lane boulevard not far from the city’s airport. The small bank played fast and loose with its assets, making loans to the grandson of a New York crime boss and a local concrete magnate who would be imprisoned a few years later for tax evasion. Regulators would eventually shut down First Commercial.

But at this moment the bank seemed to fit the Commander’s needs. Inside the branch he visited, he told an employee he was there to open a checking account. When the bank clerk looked at his new Indiana ID bearing Brittain’s name, everything seemed fine. But the bank would still have to run Brittain’s information through their fraud-check system, a post-9/11 requirement meant to crack down on terrorist financing and money laundering. Mr. Brittain told the bank clerk that he was a public relations consultant and gave an address for an apartment a few miles north. Though their system failed to note that his so-called residence was actually a mailbox at a ups Store, it flagged the fact that someone with Brittain’s name and social security number also appeared to live not in Tampa but at a trailer park more than 1,600 miles away in Gallup, New Mexico. How could that be, the clerk likely wondered. Always quick on his feet, the Commander said that, like many Floridians, he was a snowbird. It didn’t matter that a snowbird was unlikely to be in the Sunshine State in July. This was all the bank needed to hear. Before long Brittain had a new account in his name at First Commercial Bank, and he knew just what he wanted to do with it.

Soon after making an initial hundred-dollar cash deposit, money intended for veterans started pouring into the usnva via its new telemarketer. After paying professional callers their exorbitant, but totally legal, cut, much of what was left over traveled a circuitous route through thirteen different bank accounts that had been opened for the Navy Veterans Association or under the name of Bobby C. Thompson. Much of the donated money would be converted to untraceable paper currency through ATM withdrawals or checks made out to cash. At nearly the same time that these withdrawals began, funds of unknown provenance were used to purchase money orders that were then deposited into Brittain’s new account at First Commercial Bank. Putting in a few thousand dollars each month, the balance grew to $45,000 in less than two years. From the spring of 2007 through the fall of 2009, it would remain at about this level. Though he made the odd ATM withdrawal and used the account to make a few small purchases, including a burner phone and refill minutes, this money was not for general operating expenses. It served another purpose. From the very beginning of the Navy Vets scam, the Commander had established the name Ronnie Brittain and this account as a parachute to safety. Both would be ready for the day Bobby Thompson needed to cease being Bobby Thompson and flee Tampa.

That time came in October 2009, when St. Petersburg Times reporter Jeff Testerman began asking questions about a phony voter registration in the name of a nuclear sub commander named Thomas Mader. Days after the reporter’s first Mader-related queries, Thompson dusted off the Ronnie Brittain ID and disappeared from his Tampa duplex. Records from the escape-fund account show ATM withdrawals that October and November along a path leading from Tampa to Cincinnati, Columbus, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and, finally, to New York. There the initial Mader-induced panic seemed to blow over, and the Commander decided it was safe to once again stow away the Brittain identity and resume functioning as Bobby Thompson. He would continue to inhabit that assumed identity until his disastrous meeting with telemarketing boss Dick Cole at the Helmsley Hotel in June 2010. After that he scuttled the name Thompson for good, fled New York, and became Ronnie Brittain. As Brittain, he resurfaced days later in Boston, a city where he had lived many years, and many cover stories, earlier.

Upon his return to Boston that summer, the Commander stayed busy. He began hitting an ATM near Copley Square, a park in the city’s Back Bay neighborhood. He also used the Brittain identity to open three new accounts at a td Bank branch, listing his address as an apartment on a street nearby. After he had almost depleted the Brittain escape-fund account, bank records suggest that the Commander made a cross-country trip in late July and early August. ATM withdrawals this time revealed a path from Boston to Minneapolis, Seattle, Sacramento, Portland, and, finally, back to Boston. The purpose of this trip would remain unclear. Was he visiting mail drops and emptying them of incriminating evidence investigators might soon seek? Could he have been picking up or stashing Navy Veterans Association cash at various locations across the country? Had he become worried that authorities had found something that could point them to his Brittain ID? Or had he gone west to begin creating new identities?

Bank records showed that by Thursday, August 19, the Commander was back in Boston. A lot had happened while he was gone. Problems were mounting. In Florida state and federal agents had conducted their raid on the home of his assistant, Blanca Contreras, and in Ohio authorities had issued their first warrant for the arrest of the man they knew as Bobby Thompson on an identity-theft charge. The Commander knew he needed to act. Earlier that summer it appeared he had been contemplating fleeing the country. He’d gone online and visited a website offering fake passports from Australia, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, and various European nations. But by the time he returned to Boston, he seemed to have settled on staying in the United States. He just needed some new names to help make that possible.

Upon collecting his Totem Security identity haul in 1997, the Commander first utilized the names of Thompson, Brittain, Dosier, and Frazier, then set aside a pile of names he had deemed either too hard or too recognizable to use. Now he no longer had the luxury of being picky. Days after returning to Boston, he went online and began obtaining credit reports on seven of the men who applied to be hazmat security officers thirteen years earlier. He was presumably looking for telltale signs that their identities had already been compromised or that they had delinquent accounts—two possible red flags that could mean they were more likely to monitor their credit history. In trying to find the best names to adopt, he also appeared to have made notes in pink ink on these men’s old, weathered applications. On some he jotted down contextual information, apparently preparing to answer the kinds of questions he might be asked when he assumed their names. For one man he made notes about the actual location of his hard-to-find rural address in case someone asked him, “So where exactly is that?” On another he noted that the man’s last name, Delaney, was derived from Gaelic for O Dubshláine, a nice piece of trivia to pull out if anyone ever asked, “Delaney, huh? Where’s that name come from?”

With his new list of names, the Commander soon began setting up emails, practicing signatures, and researching which victims’ birthplaces had the most lenient policies for the provision of birth certificates. He would eventually obtain one of these documents in the name of a man born in Arizona in 1951 and another in the name of a man born in Oregon in 1965. Both were stamped as having been issued within weeks of running the men’s credit reports. It’s unclear if these certificates were truly state-issued documents or if they were forgeries created by the Commander himself. Creating one’s own documents was something The Paper Trip warned against and something the Commander appeared to have avoided in the past. But now, on the run, he was running out of choices and running out of time. He was forced to create new ID cards himself using the second-tier names of the men he researched that weekend in August.

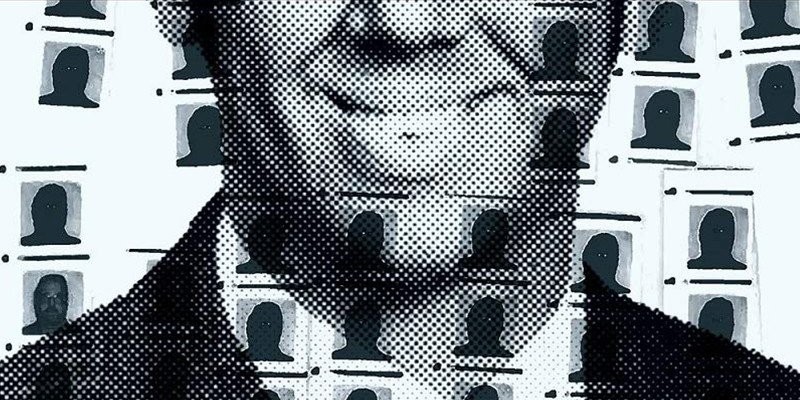

Eventually, his picture, in various states of disguise, would appear on documents proclaiming him to be Richard Overturf, Michael Delaney, Arthur Burrola, Lodi Bitsie, Kenneth Morsette, Lance Guy Martin, and Anderson Yazzie. These seven names would appear on six fake Department of Homeland Security permanent-resident cards, six fake social security cards, six fake driver’s licenses, four prepaid debit cards, one fake Massachusetts fishing license, and eight work ID cards claiming he was, variously, an administrator for Navajo Education Systems, a security consultant at LaRouche et LaRouche, a safety consultant at Boeing, an analyst at the Irish Times Corporation, a graduate assistant at Arizona State University, a transportation specialist at Interstate Storage Rentals, a sales manager at Alpha Omega Corporation, and a consultant at Guiness [sic] Records. Even on the run the Commander was a busy man capable of prodigious creativity.

Including this batch and his earlier names, the Commander used the identities of men from the Southwest dozens, hundreds, or thousands of times to establish mail drops, pay telephone-answering services, hire lawyers and telemarketers, rent storage and housing, check into hotels, open at least seventeen bank accounts, apply for insurance, incorporate two Florida corporations, make hundreds of thousands of dollars in political contributions, and file various papers and applications with numerous states and the federal government. For instance, following the election of Barack Obama in November 2008, the always paranoid Commander appeared to have grown especially concerned that, after eight years of GOP rule, he might soon need to flee the country. Three days after the historic vote, he went to Orlando and used the name Isaac Frazier to apply for a U.S. passport. Apparently, the Department of State officials who reviewed his application were concerned that a man born in 1948 was using a birth certificate issued in 1997, a likely sign of fraud. His request was denied. This was the only known example of a failed attempt by the Commander to obtain an id, a record that spoke to the great care he took in planning these efforts and his long learning curve. He was, in fact, so good that the trained professionals tracking him never quite figured out that the key to understanding his masterful wholesale theft of identities was contained within a box of newspaper microfilm stored at the New Mexico State Library in Santa Fe.

“With the right information and skills, a person can use the selective revelation of his ‘background’ to achieve the desired identity or identities,” the author of The Paper Trip once wrote. “And like a master artist applying the final brush stroke, the individual can verify that identity with the proper documentation.” By the time he was on the run in 2011, the Commander was truly a master artist, but how had he attained this status? Was it by studying the underground bible that had taught these skills to a generation of criminals? Or could there have been some other explanation for his expertise?

By the time he was on the run in 2011, the Commander was truly a master artist, but how had he attained this status?For years the man who called himself Bobby Thompson had bragged of his connection to the world of intelligence, a world where the identity-creation techniques employed by the Commander and outlined in The Paper Trip have sometimes been utilized. In a newspaper article in 1968, intelligence experts David Wise and Thomas B. Ross outlined the use of the Infant Death Identity process by Russian spies living in the United States under assumed names without the benefit of diplomatic cover. “Although there are cases where Soviet intelligence provides an ‘illegal’ with a totally invented identity, current practice . . . is to clothe an ‘illegal’ agent in the identity of another person—often, but not always, a dead man.” According to a declassified article on the Central Intelligence Agency’s website, a Cold War–era KGB officer named Willy Fisher, whose story was told in the film Bridge of Spies, operated illegally in the United States as Emil Goldfus. Called by one reporter a “Soviet master spy whose impeccable English and intimate knowledge of Western ways permitted him to melt into American life,” Fisher had obtained a birth certificate in the name of Goldfus, a boy who had died several months after his birth in 1902. Then there was Albrecht Dittrich, another so-called KGB illegal, who lived on U.S. soil for years as Jack Barsky, a name borrowed from a Maryland boy who met an early end before attaining puberty.

While it’s possible the Commander learned his techniques on his own, the man leading the effort to find him would later wonder if someone else had helped him along. “This was somebody who was highly trained and highly experienced,” said deputy U.S. marshal Bill Boldin. “What is very clear is that he obviously had training, experience, and expertise in the creation of these fraudulent identities and the ability to live as a fugitive.” As the men chasing him had begun to realize, the Commander was more than just a typical white-collar criminal. They began to wonder if he really was that thing he had told friends and associates he was—a spy.