Ann Marten’s premonitory dreams always featured her neighbor’s Red Barn, which earned its moniker not because of the color of its boards but from the otherworldly glow it emitted at dusk. In the local East Anglian lore, this trick of the light set the spot apart as a place of ill omen—and also the perfect place for trysts. It had been almost a year since her stepdaughter Maria Marten left for the barn with her lover William Corder, the son of a wealthy farmer. Maria had one illegitimate child and had recently borne another by Corder, but the baby died very young and was buried in a nearby field. In 1820s England, unmarried coupling and childbearing were cause for arrest; Corder told the Martens that the constable was coming to arrest Maria for bearing children out of wedlock, and suggested she beat a hasty retreat to Ipswich with him to get legally married. “If I go to gaol,” Maria reminded William Corder, “you shall go too.”

To avoid being spotted on their journey to the courthouse, Maria disguised herself in men’s clothing, but for some reason kept on her earrings, the green handkerchief around her neck, and the small combs in her hair. She topped off the ensemble with a man’s hat. Ann bade them farewell as they left from two separate doors and headed for the barn, where Corder said he had arranged for a carriage to meet them and take them to Ipswich.

Later, Maria’s young brother George said that the day the couple supposedly departed, he saw Corder leave the barn alone, a pickaxe on his shoulder. Corder assured the Martens that the lad must be mistaken; it was surely a neighbor planting trees on the hill. Soon the neighbors took note of Maria’s absence. Mrs. Stowe, who lived closest to the Red Barn and from whom Corder had borrowed a shovel, asked after Maria at harvest time when she saw Corder at home helping his mother. He assured her that Maria did not live very far away, despite numerous conflicting reports to the contrary.

Mrs. Stowe asked if Maria was likely to have any more children, now that they were supposedly married. “No, she is not,” Corder replied, “Maria Marten will have no more children.”

Taken aback, Mrs. Stowe replied, “Why not? She is still a very young woman.”

“No,” he said. “Believe me, she will have no more; she has had her number.”

“Is she far from hence?” Mrs. Stowe asked again.

He answered, “No, she is not far from us: I can go to her whenever I like, and I know that when I am not with her, nobody else is.”

When Maria had been gone a year, Ann still hadn’t heard directly from her once. Corder kept in touch with Ann and her husband, Thomas Marten, either by letter or on visits back to his nearby family farm. Unusually for the daughter of a poor mole catcher, Maria knew how to read and write, so her family was distressed that she hadn’t written a single letter home. At one point, Corder explained that she was afflicted by a growth on her hand that made it impossible for her to write; another time, he vowed to hold the post office responsible for losing a letter that he claimed Maria had sent to her father.

When Maria had been gone a year, Ann still hadn’t heard directly from her once. Corder kept in touch with Ann and her husband, Thomas Marten, either by letter or on visits back to his nearby family farm. Unusually for the daughter of a poor mole catcher, Maria knew how to read and write, so her family was distressed that she hadn’t written a single letter home. At one point, Corder explained that she was afflicted by a growth on her hand that made it impossible for her to write; another time, he vowed to hold the post office responsible for losing a letter that he claimed Maria had sent to her father.

As time dragged on, Ann’s horrible dreams intensified. Reluctantly, she brought her concerns to her husband: “I think, were I in your place, I would go and examine the Red Barn. I have very frequently dreamed about Maria, and twice before Christmas I dreamed that Maria was murdered and buried in the Red Barn.”

Asked why she hadn’t told him before, Ann said she was afraid that he would think she was being superstitious. Thomas Marten grabbed his mole spud—a sharp metal tool he used to kill the creatures in the ground—and made his way to the Red Barn. He began poking into its floors and soon noticed that the ground was softer where the corn harvest had recently been resting. He cleared away the earth to find the badly decomposed corpse of his daughter, green kerchief still tied stiflingly tight around her neck. Her combs and earrings were littered among the gore and exposed skeletal limbs.

He called the authorities, who did their best to assess the scene, despite not having the appropriate facilities or much experience with murder investigations in their tiny country village of Polstead. A local surgeon made notes of the state of Maria’s body while she still lay in her shallow grave, then some men lifted her body onto a door to take her to the local pub for closer examination. In their attempt to move her, her rotting hand dropped onto the barn floor. They found signs of a gunshot wound to the face and other wounds consistent with stabbing, choking, or dragging. They concluded that someone would have to find William Corder right away.

In London, a police officer located him in the family home of his new wife, whom he had found after placing an ad in The Times lamenting the recent loss of the “chief of his family by the hand of Providence” and expressing his hope to find a suitable replacement. The officer asked Corder three times whether he knew someone named Maria Marten, and each time Corder assured him that he knew no such person. Soon enough, Corder was arrested and on his way home to stand trial for his crime.

Meanwhile, the sleepy towns of Polstead, where Corder’s family lived, and Bury St. Edmunds, where the trial would be held, erupted with activity. Reporters flocked from all of the nearby towns and even from London to cover the inquest and trial. The brutal and salacious nature of the crime piqued villagers’ curiosity. Near the Red Barn, a preacher drew a crowd of nearly five thousand onlookers as he decried the heinous acts of Corder, who already bore the new moniker “Corder the Murderer” in town gossip and folk song. Throngs of visitors were also entertained by a camera obscura and various impromptu plays depicting the crime in grisly detail. William Corder’s mother had to threaten the playwrights over use of her son’s name, as he had not yet stood trial—but still, “Corder” was on everyone’s lips.

By the time the trial began on August 7, 1828, people from all walks of life had flooded Bury St. Edmunds in frenzied anticipation. Rain poured down on the umbrellas and bonnets of the gawkers; women were generally barred from entering the court, so they mashed their faces and dresses against the courtroom windows, reportedly breaking a few panes. Mischievous individuals passed the time by yelling, “He’s coming! He’s coming!,” which would cause a fresh commotion until the spectators realized it was a false alarm. When the court officials arrived, they had considerable trouble getting through the unruly mob; some had their forensic wigs snatched and one even lost his gown. Finally Corder appeared, his youthful, freckled face floating above a beautiful corbeau surtout with a velvet collar, paired nattily with silk stockings and pumps.

The prosecution was damning on the first day of Corder’s trial. The court proceedings had to pause periodically because of noisy riots outside, and beleaguered constables promised to imprison the instigators should they persist. When court adjourned for the day, enterprising onlookers (many of them women—propriety be damned) climbed ladders onto the roofs of nearby buildings to attempt to get a look at the prisoner. Women of all classes showed keen interest in the outcome of the trial; one upper-class woman told a reporter she was looking forward to witnessing the hanging of someone who so inhumanely butchered another woman. Their weight threatened to collapse the roof of the courthouse. As a result, the ban on women in the courtroom was lifted. Constables stayed on guard for more shenanigans from rowdy onlookers for the rest of the trial. The next day, Corder mounted a weak defense. After denouncing his unfair treatment by the press, he claimed that a distraught Maria had shot herself in the aftermath of an argument. Prosecutors called his explanation ludicrous, given all of the other injuries on Marten’s body. After deliberating for about twenty-five minutes, the jury returned a guilty verdict.

Corder dropped his chin to his chest.

“William Corder,” the lord chief baron began, adjusting his wig, “It now becomes my most painful but necessary duty to announce to you the approaching end of your mortal career.” Corder shook violently throughout the rest of the lord chief baron’s speech, his jailers occasionally propping him up to the bar. “Nothing remains now for me to do, but to pass upon you the awful sentence of the law. That sentence is—that you be taken back to the prison from whence you came and that you be taken from thence on Monday next, to a place of execution and that you there be hanged by the neck until you are dead; and that your body shall afterwards be dissected and anatomised; and may the Lord God Almighty, of his infinite goodness, have mercy on your soul!” The lord chief baron left the courtroom immediately and stepped into a waiting carriage, while the jailers carried a sobbing Corder back to his cell.

The excitement of the trial gave way to the buzz of activity surrounding the execution. The habitual hanging tree would not do, as William Corder would have too far of a trip through the dense crowd from the jail to the tree, so workers burrowed a hole right through the side of the jail, putting a platform underneath the gallows that would drop out at the right moment.

Public executions were always charged events, but our usual image of mobs howling for the blood of the condemned is incomplete. Hanging offenses varied greatly, and riots sometimes erupted at the gallows as friends and family attempted to save their loved ones from the rope. This urgency was heightened by the knowledge that surgeons lay in wait to dissect the bodies of the worst criminals, a fate anathema to most people at the time. Eventually the association between dissection and murderers was so strong that it was very difficult to convince people to promise their bodies willingly to the cause of science.

Corder was so unpopular and his crime so heinous that no one was likely to risk their life to save his at the end. But with a crowd this size and a trial this tumultuous, the village officials had to take every conceivable precaution.

While the men building the gallows busted the bricks on the outside of the jail, Corder wrote his confession about shooting Maria Marten and burying her in the Red Barn. Come Monday, some ten thousand pairs of eyes were fixed on Corder as he stepped onto the scaffold. Corder scarcely had time to take in the beautiful rolling hills and evergreen forests surrounding the Bury St. Edmunds jail before his eyes were closed forever. After just a two-day trial, his short life was over. But his corpse’s work—and the work of relic hunters—had only just begun.

As Corder’s corpse was carried back into the prison, the crowd roiled; spectators clamored for pieces of the hanging rope, a typical souvenir of infamous executions. Contemporary journalists reported that one museum official had even traveled from Cambridge in hopes of buying it for his collection. For his part, the hangman confirmed slyly, “What I got, I got, and that’s all I shall say except that that was a very good rope.”

An hour after William Corder’s death, the county surgeon, George Creed, was already slicing a long line down the center of his body, peeling back the skin to expose the chest muscles before laying the body out for the public to shuffle past and gawk at. This was a common practice at the time and part of the public humiliation of murderers implemented to deter future criminals. At least Corder’s body still wore his silk stockings and trousers while thousands gawped at his flayed corpse. By early evening, the public’s bloodthirst finally sated, the professionals swarmed upon Corder’s corpse. Artists made death masks and phrenological plaster casts of his head. The enterprising hangman collected what remained of Corder’s fine clothing and the naked cadaver was transferred to the county hospital in Suffolk.

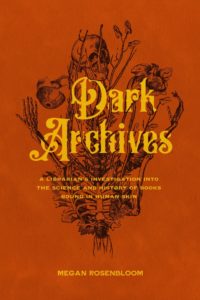

The next day, medical students and anatomists fully dissected Corder, and since any part of a dead murderer was up for grabs to local doctors, it was likely that at this point they removed a sizeable piece of his skin to bind a book about his trial.The next day, medical students and anatomists fully dissected Corder, and since any part of a dead murderer was up for grabs to local doctors, it was likely that at this point they removed a sizeable piece of his skin to bind a book about his trial. Mention of this book is absent from even the most detailed contemporary accounts of Corder’s story; that could be because Dr. Creed made it for his own personal collection, where it remained until he bequeathed it to a fellow doctor before it finally made its way into a public museum. Creed made an anatomical wet specimen out of Corder’s heart, and began preparing his skeleton for eventual articulation and display in the hospital.

“Thus I shall be able to show visitors to our hospital,” Creed wrote, “at distant periods, the skeleton, heart and cast of the outward features of the head and face of this horrid murderer.” Creed was so pleased with the head’s pronounced bumps—they corresponded with phrenological ideas about the secretive, greedy, and destructive behavior that Corder exhibited in life—that he sent the cast to one of the leading lights in the phrenological world, Dr. Johann Spurzheim. “I had a great pleasure in finding, on my return from Paris, the cast of the murderer Corder,” Spurzheim wrote warmly, “which you were so kind as to send for my collection, and for which I give you my best thanks.” Aside from the alluring head bumps of great geniuses, phrenologists were most intrigued by what their then-popular pseudoscience could tell them about the inner workings of the most depraved murderers. In addition to Creed’s findings, Spurzheim noted that Corder must have been a man of low self-esteem and inferior intellect, but he was much intrigued by Corder’s oversize region of marvelousness, or inclination toward religiosity or superstition. “I should like to know some particulars of Corder’s private life—concerning his large tune and imitation; whether and how they have been active for themselves, or in combination with amativeness—secretiveness and acquisitiveness. The great development of this marvelousness, too, excites my phrenological curiosity.”

Just as Corder was being dismembered, so, too, was the Red Barn. Relic hunters stripped off souvenirs from the location of the crime and made them into snuff shoes (for storing tobacco) and other items. At a time when policing was just becoming a profession and shortly before the rise of the fiction detective story, newspapers and books breathlessly reported the worst crimes of the day. Cases like Corder’s contributed to a collective desire to own physical mementos from famous murder scenes, now called murderabilia.

A complex mix of motivations can contribute to the psychological urge to collect murderabilia. With these objects, the murderer shifts from the consumer of other people’s bodies to the one being consumed (both physically, as he is made into objects, and culturally, as he becomes the subject of pop cultural works such as plays or murder ballads). Owners of murderabilia feel a renewed sense of control, which may help to explain why so many women were avid spectators at Corder’s trial, execution, and dissection. The “morbid gaze” that gawkers exhibited as they marched past Corder’s opened body is the same that draws us to true crime today: the push-pull between repulsion and fascination with the corpse, mingled with a thirst for vengeance against violence, turns death into entertainment for the living.

To this day people gape at Corder’s corpse—or at least alleged pieces of it—at the Moyse’s Hall Museum in Bury St. Edmunds. Corder’s skin book is just one of the English books from this time period that purport to be made from the hide of a murderer of women. At Bristol’s M Shed museum, a supposed anthropodermic binding covers the 1821 trial transcript of John Horwood, who—after an escalating obsession and attacks, including throwing sulfuric acid—murdered Eliza Balsam with a rock while she was out on a walk. In Devon, the alleged hide of the rat catcher and wife poisoner George Cudmore covers The Poetical Works of John Milton. Where murderabilia is concerned, not even a plaster death mask can compete with the unique, horrific object that is the murderer’s skin-bound book. When the object was once part of the murderer himself, his corpse is commodified, which scratches a psychological itch for revenge.

___________________________________