On October 12, 1964, two days before her 44th birthday, artist Mary Pinchot Meyer set a fan on her canvas to help the paint dry, pulled on a blue angora sweater against the cold, and left her Georgetown studio for a walk. Meyer often took walks by the Potomac. Friends said that it was one way that she processed her grief over the death of her ex-lover the prior year. She passed a limousine, and waved to a friend, the wife of a covert CIA operative and member of the Washington aristocracy. Meyer traveled easily in the Washington elite—a graceful, serious blonde, a Vassar graduate, the ex-wife of CIA deputy director Cord Meyer. Her art-making seemed like another life altogether, part of the soul searching she’d done after her nine-year-old son was struck and killed by a passing car, soul-searching that include orgasmic therapy, LSD, and a deepening commitment to world peace that some Washington insiders have claimed led to her death.

Meyer had just entered a dense woods near the Potomac when her assailant seized her from behind and shot her in the head. She called for help and struggled free, leaving blood streaks on a nearby birch, but her attacker dragged her to the edge of the river and shot her again in the chest, killing her. Within ninety minutes, a crew of police had descended to the crime scene. By the end of the day, they had a suspect: a lone black man named Ray Crump, who had been witnessed standing near the body. The arrest and conviction fell into place fast, despite the fact that Crump’s diminutive physique and confused mind didn’t suit a killing so merciless and clean, or that the murder weapon was never found.

Perhaps Meyer had found out something fishy about the assassination of John F. Kennedy and its potential cover-up. And because she’d been both a longtime friend and a lover to Kennedy…she’d wanted the truth known.What motivated the lightning speed of the hunt? Meyer’s murder was high profile. Indeed, some members of the Washington intelligence community seemed to know about Meyer’s death before the body was even identified that evening, writes Peter Janney, the son of a CIA officer and author of an admiring book on Meyer called Mary’s Mosaic. The CIA operatives were already aware that Meyer was dead, Janney speculates, because it is possible that they had planned her killing. Perhaps Meyer had found out something fishy about the assassination of John F. Kennedy and its potential cover-up. And because she’d been both a longtime friend and a lover to Kennedy, according to witnesses and to Kennedy’s own passionate, hand-scrawled letter to Meyer, auctioned off in 2018, she’d wanted the truth known. Janney contends that this knowledge cost Meyer her life.

“The crime scene on the C&O towpath within ninety minutes after the murder of Mary Pinchot Meyer on October 12, 1964,” courtesy of Peter Janney, Mary’s Mosaic (2013)

“The crime scene on the C&O towpath within ninety minutes after the murder of Mary Pinchot Meyer on October 12, 1964,” courtesy of Peter Janney, Mary’s Mosaic (2013)

The summer after Meyer’s death, after a defense by a trailblazing black woman lawyer named Dovey Roundtree, Ray Crump was acquitted of all charges, and Meyer’s murder became once again unsolved. But in the years that have passed since then, a series of accusations and counter accusations among her former associates have connected her killing to conspiracies ranging far beyond her own private life and to the assassination of JFK, who’d trusted Meyer so deeply that she had been a fixture in the Oval Office in 1963.

Beautiful, self-possessed Mary Pinchot Meyer has inspired multiple books, articles, and most recently a limited TV series currently being written by David Seidler (The King’s Speech) for Warner Bros. Some tales dig into Meyer’s significant relationship with Kennedy and what she might have known that endangered her. Others assign her murder to Ray Crump after all, who went on to a career of rape and arson, and to align his acquittal within the rising racial tensions of America in 1965. A cornucopia of confusing stories abound regarding Mary Pinchot Meyer’s missing diary, also described as an “artist’s sketchbook,” and whether it held details of her affair with JFK or her thoughts on the conspiracy surrounding his assassination or simply color swatches and some personal notes. This so-called “Hope Diamond” of the Kennedy assassination investigation has allegedly gone up in flames—a loss not just to the country’s history, but also to our own art history.

Mary Pinchot Meyer became involved with members of the Washington Color School in the late 1950s, when she’d sought solace and self-exploration after the loss of her son Michael and her subsequent divorce. She painted, hung out at jazz clubs, smoked marijuana, and began a romantic entanglement with Kenneth Noland, one of the best-known American color field painters, whose paintings of concentric color rings now hang in many major museums. Noland “soak-stained” his canvases, which meant he applied thinned paint directly to unprimed cloth, causing it to absorb directly, and giving the artist “one shot” at getting it right.

“Beginning,” magna on canvas painting by Kenneth Noland, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, 1958

“Beginning,” magna on canvas painting by Kenneth Noland, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, 1958

While this may seem a small difference in technique to us now, in the 1950s it was revolutionary. Noland sought a more direct artistic experience, an erasure of the emotional splashes of his predecessors for the sake of pure color and flatness. Taking away a painting’s priming and a painter’s ability to revise his work made the act of painting itself singular, intense, and immediate, an improv, like the jazz solos Noland and Meyer watched at clubs like the Bohemian Caverns and the Howard Theater. Noland’s process deeply influenced Meyer, and she joined him in the powerful and uncynical longing of the late Fifties/early Sixties bohemian culture to find new pathways to transcendence. The pair began taking weekly train trips up to Philadelphia for therapeutic bodywork sessions with an orgonomist, who helped them release psychological blockages to their orgasm function.

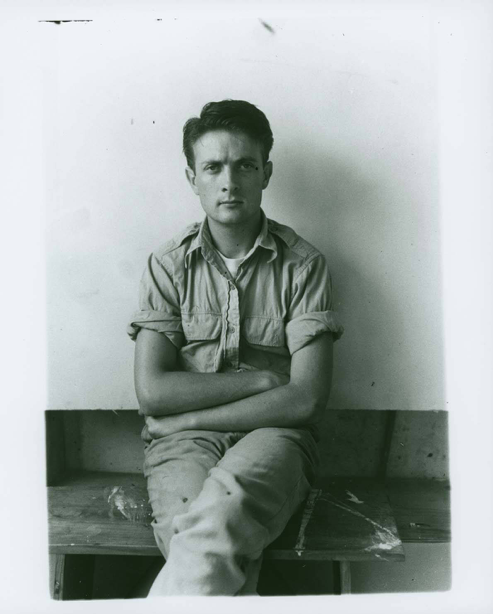

Kenneth Noland © Black Mountain College Research Project. North Carolina Museum of Art. Western Regional Archives

Kenneth Noland © Black Mountain College Research Project. North Carolina Museum of Art. Western Regional Archives

“What does Kenneth Noland have that I don’t have?” Jack Kennedy reportedly asked Meyer during that time, frustrated by her perennial denial of his advances.

“Mystery,” she replied.

But Noland wasn’t the final destination on Meyer’s pilgrimage. She would also turn to the mind-expanding power of LSD, personally visiting with Timothy Leary at Harvard and asking him to teach her how to guide another person’s experience with the drug. When Leary offered to mentor the person himself, Meyer refused. She had a very influential friend, she said, whose anonymity needed protecting, yet she did want him to experience the consciousness-awakening of acid. Meyer had finally transitioned from JFK’s friend to his lover, according to Peter Janney, and in 1962 she and the president were secretly and deeply involved. The affair cooled by 1963, but Meyer remained a trusted contact.

No one knows if JFK did experiment with LSD with Meyer, but rumors persist, championed by followers of Leary and “proven” by dramatic changes in Kennedy’s international policies in 1963. In June, Kennedy appeared to make an about-face on his pessimism that peace could ever be achieved with the Soviet Union and gave one of the most remarkable speeches of his career, on world unity, at American University. “We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal,” Kennedy declared. “… Is not peace, in the last analysis, basically a matter of human rights: the right to live out our lives without fear of devastation… ?” Kennedy’s speech so impressed Krushchev that the Soviet leader had it rebroadcast throughout his country. This led to renewed negotiations with Soviet leadership and the nuclear test ban treaty. It also severely disappointed war hawks in Washington.

Mary Pinchot Meyer, at far right, the day that the U.S. Senate ratified the president’s limited nuclear test ban treaty, courtesy of Peter Janney, Mary’s Mosaic (2013)

Mary Pinchot Meyer, at far right, the day that the U.S. Senate ratified the president’s limited nuclear test ban treaty, courtesy of Peter Janney, Mary’s Mosaic (2013)

Let’s leave who might have killed the president and how they did it to the myriad volumes and movies devoted to it. Kennedy was shot in his motorcade in Dallas just as Meyer’s star was ascending in the D.C. art world. Her solo exhibition at Jefferson Place Gallery received a strong review in the Washington Post two days after JFK’s death. “Her work has always shown a quality which made one want to see more,” wrote Leslie Judd Ahlander, calling Meyer’s color choices “luminous and carefully thought out” and noting how the colored areas seem to set the circles to “revolving.” How well did anyone, including Meyer, absorb the critical praise through the nation’s fog of shock and sorrow? It’s hard to know. Nevertheless, Meyer had turned to art to survive grief before, and she retreated even more into painting. In the year afterward, her work was included in her first world-touring exhibition, organized by the Pan American Union. She died before it opened in Buenos Aires.

“The tragic death of Mary Pinchot Meyer on the C&O towpath … stilled one of the truly creative talents in the Washington metropolitan area,” wrote James Hilleary, a Washington Color School architect and painter, in a 1964 tribute in the Post. “She was an artist moving toward, rather than having arrived at, her fullest potential.”

Meyer’s best-known work, “Half Light,” now owned by the Smithsonian, is a shaped canvas, a circle. The paint is synthetic, giving it a different luster than oil. The quadrants were inspired by the four elements—earth, air, fire, and water—and, as the Post reviewer notes of Meyer’s work, her contrasting color choices almost seem to spin the motionless canvas. “Half Light” appears to turn, yet holds itself still, whole and in balance.

This serene painting, one of the last that Mary Pinchot Meyer completed, says nothing of her beauty, of her lovers, of her lost son, of her pilgrimages to heal, or her anger and grief over the death of John F. Kennedy. It is the key to no conspiracy or murder, even her own. But it speaks volumes to the time she lived in, its revolutions and longings for unity, and to a woman who pursued her truth until her last breath.

Mary Pinchot Meyer, Half Light, 1964, synthetic polymer on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Quentin and Mark Meyer

Mary Pinchot Meyer, Half Light, 1964, synthetic polymer on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Quentin and Mark Meyer