It was raining. Not a particularly auspicious day. It had rained yesterday and it would probably rain tomorrow.

Bannerman remembered a cartoon he had seen once in an old Punch magazine. Two crocodiles basking in a jungle swamp, heads facing each other above the muddy waters. One of them was saying, ‘You know, I keep thinking today is Thursday.’ Bannerman smiled. It had amused him then, as it amused him now. What bloody difference did it make . . . today, tomorrow, yesterday, Thursday? It was ironic that later he would look back on this day as the day it all began. The day after which nothing would ever be quite the same again.

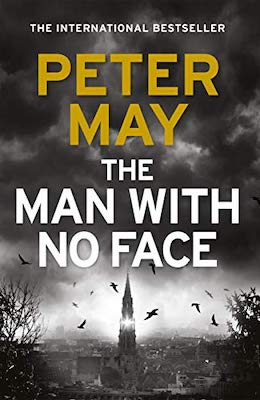

But at the moment, so far as Bannerman knew, it was just a day like any other. He gazed reflectively from the window a while longer, out across Princes Street, the gardens beyond, and the Castle brooding darkly atop the rain-blackened cliffs. Even when it rained Edinburgh was a beautiful city. Against all odds it had retained its essential character in the face of centuries of change. There was something almost medieval about it; in the crooked hidden alleyways, the cobbled closes, the tall leaning tenements. And, of course, the formidable shape of the Castle itself, stark and powerful against the skyline.

In the office the day had barely begun. Reporters sat around reading the morning papers, sipping black coffees and nursing hangovers.

‘Morning, Neil.’

Bannerman turned from the window in time to see George Gorman drifting past. ‘Morning,’ he called after him, and watched the retreating figure as he headed for the news desk. Bannerman felt some sympathy for his news editor. Gorman was a dapper little man, good at his job without being inspired, nervous under pressure. A nice man, just waiting for the axe to fall.

It had already fallen on a number of his colleagues: John Thompson in features, Alex McGregor in sport. And there had been casualties in the reshuffle on the subs desk. It had been inevitable really, ever since it was announced that Wilson Tait was being brought up from London to fill the recently vacated editor’s chair.

The Edinburgh Post had never been able to boast a particularly high circulation. For years it had lived off its reputation as a serious newspaper of quality and reliability. It was read by politicians, members of the legal and medical professions, teachers, academics. But their patronage alone was no longer enough to balance the books. Profit was more important than prestige. Hence the appointment of Tait, a hard newspaperman of the old school; a Fleet Street-toughened Scot returning to his old hunting grounds and bringing with him his personal hard core of hatchet men whom he was moving into key editorial positions. Blood was being spilled. And only the approaching general election – just three weeks away – had provided a stay of execution for Gorman. When it was over, he would receive a quick sideways promotion to make way for one of Tait’s rising stars. And while Gorman was allowed to vegetate quietly in some out-of-the-way office with an ambiguous brief from the editor, the paper would move slowly but surely downmarket, where it would endeavour to pick up new readers, almost certainly alienating its existing readership in the process.

It was then, Bannerman thought, that he would have to consider his own future with the paper. Though that was already in doubt. He and Tait had clashed almost immediately over Bannerman’s role with the Post. And there was no love lost between them.

It was then, Bannerman thought, that he would have to consider his own future with the paper. Though that was already in doubt.The phone rang on Bannerman’s desk. ‘Bannerman.’

‘Good morning, Neil. You’re in early.’

Bannerman smiled. ‘What is it, Alison?’

‘The editor wants you.’

‘You mean he’s in early, too?’

‘Ha, ha.’

‘I’ll be right there.’

Alison smiled up at him when he came into her office. ‘Set your alarm an hour early by mistake?’

Bannerman grinned. She was a good-looking girl, easygoing but very efficient. ‘Actually I came in early to ask you if you might be free tonight.’

‘Oh, that’s nice. I am actually. But you’re not.’

Bannerman frowned. ‘Oh? You know something I don’t?’

‘Only that you’ll be too busy packing. I’ve just booked you on the first flight to Brussels in the morning.’ She nodded towards the editor’s door. ‘Orders from His Imperial Highness.’

She watched him go through into Tait’s office and wondered what it was that was so attractive about him.

Tait was hunched over his desk in shirtsleeves. He glanced up momentarily from his paperwork as Bannerman knocked and came in. ‘Take a seat. I’ll be with you in a moment.’

Bannerman sat down and watched the other man patiently. Tait liked to make you feel that he was seeing you on sufferance, that you were interrupting much more important matters. Bannerman was not impressed.

The editor was a small man and had the arrogance and puffed-up sense of self-importance of many small men. A compensation for lack of height. He was of indeterminate age and could have been anything between forty and sixty. His hair was steely grey, cut short above a squat, ugly face.

He gathered together several printed sheets and slipped them into a folder before looking up again. He surveyed his investigative reporter with caution. He disliked him, but was also intimidated by him. By his calm, powerful presence, his obvious self-confidence. Bannerman didn’t jump, as the others did, on Tait’s command. And that annoyed him.

‘I’m sending you to Brussels for a few weeks,’ he said.

‘Oh?’ Bannerman endeavoured to show no surprise.

‘We need some good stuff on the EEC in the couple of weeks after the election. Corruption, fraud, political back-stabbing, that kind of thing. Particularly when Common Market issues have been given such high priority in the election speeches of the major parties.’

Bannerman gazed at him thoughtfully. ‘Why so keen to get me out of the way?’

Tait leaned back in his seat and eyed Bannerman coldly. ‘Because I need time to consider what I’m going to do with you. You’re a troublesome bastard, Bannerman. A one-man band. I want to build a team here and there’s no room for buskers.’

Bannerman pursed his lips thoughtfully and Tait watched him with apprehension. Bannerman wasn’t tall, perhaps five feet nine or ten, but he was stocky, broad, and gave the impression of a bigger man. Tait knew from personnel records that he was thirty-five, but it would have been difficult to judge had he not known. He could have been younger, or older. Dark, wiry hair without a trace of grey fell carelessly across his forehead. He was not what Tait would have thought of as good-looking, but he had a certain presence, and there was something compelling in the gaze of his hard blue eyes.

Bannerman said, ‘Maybe you would rather I got a job somewhere else, Mr Tait.’ His voice was flat, toneless.

Tait grinned maliciously. ‘Trouble is, Bannerman, you’re too good just to ditch. Probably the best investigative journalist in Scotland right now, and very highly regarded south of the border. I’d like to keep you. But on my terms.’

‘I’m flattered. Maybe I should be asking for a rise.’

Tait laughed. ‘Cheeky bastard!’

Bannerman tilted his head. ‘So long as we both know where we stand.’ And he knew that he was going to have to think about his future sooner than expected.

__________________________________