I saw Ocean’s Eleven almost ten years after it was released. The movie fed into a lifelong fascination with villains. Confidence men, assassins, gunmen—each shows the blurred moral lines I crave in crime fiction. Now, ten years later, I’m still immersed in heist novels, Danny Ocean, all his ilk, and that darker side of life. Over and over in my search for more of the same, I find myself in the 1970s.

In a decade rife with cultural fear and paranoia, is it any wonder that criminals, thieves, murderers, and con artists headlined some of the most popular crime fiction of the 1970s? The world seemed in chaos. Scarred veterans of Vietnam returned home to a United States in the throes of political corruption and scandal. The recession of 1973 weakened the economy, and the détente with the looming specter of communism and nuclear war left the United States, and the world, in a time of doubt and fear. It was the ideal time for thieves, and looking back, we can trace some of their evolution.

Crime fiction had continued unabated for fifty years since the Golden Age, with Christie and Sayers, but in the latter half of the Twentieth century, thieves and stupendous heists suddenly seemed to become a focal point. Certainly, the traditional protagonists of crime fiction, detectives and private eyes, were still the undisputed heroes of the genre. However, detectives began to give way to a new hero, one unburdened by the restrictions of society. Some of the most popular authors of the last century explored these anti-heroes. The life of someone whose greedy nature was no deterrent to their utility as a protagonist.

It’s never a bad time to take a look back, and to do that, I’ve gathered seven classic master thieves of the 1970s. Most had been around for a few years or more before the 70s, but their careers began or ended during this time. Some of them seem determined to do good; others are fully corrupt. Each, however, reflects the themes of their decade, and most, if not all, are enduringly remembered and loved today.

The Saint, by Leslie Charteris

The Saint is a long-running classic of crime literature. Created in 1928, Charteris’s character Simon Templar is a do-gooder gentleman thief, equipped with all the necessities—an excellent fashion sense, a sharp wit, courage, and a moral imperative to liberate wealth and redistribute it into the hands of those who need it most. Of course, he is not above keeping a percentage for himself—after all, a good thief needs operating expenses. Who could begrudge him that? His nom de guerre is well-known by the police who labor unfailingly and unsuccessfully to find him.

Meet the Tiger was Charteris’ first book featuring the character, but after 1963, other authors collaborated with Charteris. My favorite collaboration is Fleming Lee’s The Saint and the People Importers (1971), despite some who feel that the earlier works are better. Still, this volume’s take on immigration and injustice is something to appreciate, though it shows its age at points. I include the Saint and his long history because his antiheroic pulp thriller characteristics make him the perfect starting point.

Parker, by Donald Westlake writing as Richard Stark

Parker, the only name the character is known by, is probably the quintessential master thief of the decade, because he is only a thief. Anti-hero does not apply here. Instead, the Parker novels are all about the workings of crime, usually in a formula of Parker trying to retrieve money he believes is his, by right of theft, from other mobsters or criminals. Butcher’s Moon (1974) was the last Parker book until 1997, and it remains my favorite for its connections with the previous books and characters.

Parker is unlike most of the other characters on this list in his total lack of concern for moral lines. Parker is truly amoral, ruthless and unscrupulous. What makes for pleasurable reading is Westlake’s smooth prose and refreshing character—we can’t respect Parker or even really relate to him; still, he’s anything but boring.

John Dortmunder, by Donald Westlake

Yet another creation from the endless mind of Westlake, John Dortmunder could be a sort of antithesis to Parker. Dortmunder is the mastermind of comic capers, the first being The Hot Rock (1970). He is a career criminal and an even better planner than Parker, as most of Parker’s plans depend on bloodshed, rather than ingenuity. Dortmunder, however, does not have the same ruthless, cold brutality. Like Parker’s plans, Dortmunder’s plots invariably fail, resulting in hilarity.

Westlake’s writing style is equally different. Where Richard Stark is spare, not a word wasted, Westlake under his own name takes advantage of the everyday for a humorous, practically bouncy read. Not even Dortmunder’s patented pessimism can destroy the light-hearted tone.

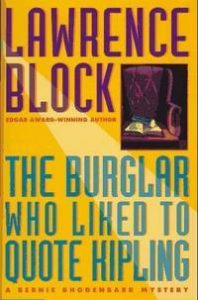

Bernie Rhodenbarr, by Lawrence Block

Bernie Rhodenbarr is another victim of comic caper misadventures, written by the inimitable Lawrence Block. The Burglar Who Liked to Quote Kipling (1979) offers something different than the others—Rhodenbarr wants out, but selling books just isn’t profitable enough. Besides, who would choose retail over burglary?

Block and Westlake were friends and writing partners, which could explain some of the similarities between Rhodenbarr and Dortmunder. Both series have a dry wit, and though the characters can come off as ridiculous, the dialogue makes them seem like real, if odd, people. However, where Dortmunder is focused mostly on his heists, the Rhodenbarr books feel more like chronicles of the everyday life of an unfortunate burglar.

Philip St. Ives, by Ross Thomas writing as Oliver Bleeck

Ross Thomas’ The Highbinders (1974) is the fourth novel featuring Philip St. Ives, who might be a thief if you squint hard enough. St. Ives is a professional mediator between thieves and their victims, or sometimes the law. Still, he hunts down stolen items and crosses and re-crosses the line of the law often enough. Many of his adventures are jet-setting, world-traveling mysteries, where his role is as an investigator more than a thief. The Highbinders find St. Ives after a stolen jewel-encrusted sword, but it seems there might be more than one thief involved.

The St. Ives novels are written in first-person, like the Rhodenbarr novels. I am pathologically incapable of resisting a good first-person narrator, and I was hooked permanently when I read, “They had let me keep my watch, my clothes, my headache, and my pink carnation. The carnation looked old and tired and bedraggled and I felt that we had a lot in common except that it still smelled nice.”

Frank Ryan, by Elmore Leonard

I started this list looking for series characters whose careers made them worthy of the title “master thief.” Naturally, I had to stretch the definition, and Frank Ryan is one of those exceptions. You can’t write a list like this and leave off Elmore Leonard. It would be a sin.

Ryan is a used-car salesman, but he thinks he’s got a plan for armed robbery that will leave him and his partner not only successful, but happy to boot. In fact, he creates a set of inviolable rules to be their guiding star. Of course, rules are meant to be broken, and the consequences come home with a vengeance in Swag (1976). Ernest Stickley Jr., the partner, returns in Stick (1983).

Tom Ripley, by Patricia Highsmith

This is another outlier on the list. Compared to some of the plot-driven thrillers on this list, Patricia Highsmith offers more psychological work, a deep dive into characters less defined by snark and sarcasm and rather by their inexplicable appeal. The Talented Mr. Ripley, like the Parker novels, is about a amoral sociopath. The difference, however, is his charming personality. The gentleman murderer seems to drag the reader in and carry him along good-naturedly, even through the blood he leaves in his wake.

Of course, Ripley is not a thief by trade, though he did successfully steal Dickie Greenleaf’s identity, and along with it, his wealth. I include him in the list because this confidence man and murderer gives us a disturbing but somehow realistic look into a truly unscrupulous mind. The Talented Mr. Ripley deals with themes of wealth, identity, and façade. These continue to suffuse the second volume of the Ripliad, Ripley Under Ground (1970), as Ripley kills to protect his art forgery scheme, Derwatt Ltd.

Ripley seems a suitable end for the list, for he exemplifies the obsession all these thieves share. Some are comic, most are relatable, but all are obsessed with wealth and simultaneously corrupted by that obsession. The circumstances are often unbelievable. The escapes can strain credulity. Even so, we keep reading.

* * *

Tom Wolfe, author and essayist, once referred to the 1970s as a “me” period, where the community was eclipsed by the individual. Self-will and self-determination ruled, perhaps to bring a forgotten focus back to the individual, or perhaps to fight the feared ideals of Communism. Whatever the reason, the rise of the master thieves in the 1970s would seem to confirm Wolfe’s assertion.

These books are endlessly entertaining. More so than entertainment value, however, the master thieves offer character studies, even in the pages of books seemingly ruled by plot. By exploring a wide range of thief roles—Robin Hood, go-between, burglar, salesman-turned-robber, murderer and imitator—these novels demonstrate a constant struggle between the limits of the law and the psychology of the law-breaker.