David Fincher is one of those filmmakers for whom every new movie feels like an event. Partly this is due to his pickiness: while the obsessive, exacting director isn’t exactly late-period Stanley Kubrick (or early period Terrence Malick) when it comes to reclusively, he has always been picky, having only directed 11 movies—including his latest, the ‘40s Hollywood drama Mank—in almost 30 years.

In anticipation for his latest effort, available to stream on Netflix, I wanted to look at the many cinematic influences on his body of work—specifically the numerous noirs, mysteries and thrillers that have informed his dark artistic vision.

This is not to say that Fincher or his collaborators were specifically inspired by all of the films listed below, nor even that he or they were necessarily aware of all of them in the first place. But the collective unconscious of cinema is a deep pool with many far-reaching streams and rivers. Viewers who enjoy dipping in a toe by way of Fincher’s filmography might be interested in exploring some of the deeper pockets.

Alien 3 (1992)

Despite the initial disappointment with which this film was met, including Fincher’s own (owing to production troubles and studio interference), his entry in the popular gothic horror/space opera series has aged remarkably well. Visually, it’s almost as arresting as the films that proceeded it, particularly in the way it harkens back to the German expressionist influences found in Ridley Scott’s original—Metropolis, Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in particular. Fincher brings to the table a new subterranean, sepia and rust-tone aesthetic, similar to that found throughout the science fiction films of Eastern Europe cinema in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s—surreal visions of the apocalypse such as Stalker, On the Silver Globe, O-bi, O-ba, The End of Civilization and Letters from a Dead Man (all of which you can find streaming via this excellent series curated by exmilitary).

Seven (1995)

The first of Fincher’s films to explore the subject of serial killers (unless you count the Xenomorph from Alien 3, which you absolutely could), this film is pure horror-noir, “an Ellroy story set in a David Lynch world” to quote the great Megan Abbott. (With all due respect to Brian De Palma, it’s a real shame we missed out on Fincher’s planned version of Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia, although he did contribute to a 2016 graphic novel adaptation.)

Along with some obvious influences of serial killer cinema—Fritz Lang’s M, Michael Mann’s Manhunter, Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs, any number of religiously-drenched Giallo films—Fincher has cited the post-Exorcist thrillers of William Friedkin as a touchpoint, particularly his notoriously controversial gay underworld murder mystery Cruising, which, like Seven, trades in the aesthetics of sadomasochism and leads to a devastatingly nihilistic ending of evil triumphant and transfigured.

The other main touchpoint for Seven is the first entry in Alan Pakula’s “Paranoia Trilogy”, 1971’s Klute. Like Cruising, it is the story of a detective’s search for a killer amidst New York’s underworld flesh trade. Like Seven, it involves a pair of mismatched investigators stumbling their way through a world shrouded in darkness—both figuratively, as well as literally. Pakula’s thrillers are all set in a world of omnipresent shadow and night, and it’s in them we find the biggest influence on Fincher’s own aesthetic.

The Game (1997)

Pakula’s influence is even more apparent on Fincher’s third effort, this puzzle box thriller about an uber-rich venture capitalist who gets embroiled in a deadly criminal plot masquerading (or is it?) as a role-playing game. The seemingly omnipotent conspiracy at the film’s center brings to mind the second of Pakula’s thematic trilogy, The Parallax View. The Game contains a direct homage to that film’s most iconic scene, having Michael Douglass’s hero subjected to a sinister psych evaluation that includes a film montage made purely of disturbing imagery.

After Pakula, the director Fincher brooks the most comparisons to is Alfred Hitchcock, and The Game’s central conceit and numerous dazzling set pieces definitely recall various of Hitch’s wrong-man thrillers—The 39 Steps, Saboteur, and North By Northwest (that film’s iconic airplane-cornfield chase would feel right at home in The Game). But the one Hitch film to which The Game is most spiritually tied is Vertigo, what with its San Francisco setting, icy blond femme fatale, and thematic obsession with suicide by jumping.

(To this latter point, The Game would also pair well with the third entry in Roman Polanski’s “Apartment Trilogy”, the surreal and terrifying The Tenant.)

Fight Club (1999)

Fincher had described The Game as a secular version of A Christmas Carol, as well as his spin on The Wizard of Oz. Both could equally describe his next film, the zeitgeist-defining adaptation of Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club. Its famous third-act twist also drew immediate comparisons to Hitchcock’s Psycho, while Brad Pitt’s charismatic and (as its detractors will be quick to mention) problematic anti-hero stands as an updated version of A Clockwork Orange’s Alex Delarge. Similarly, the arc of Fight Club’s nameless Gen-X protagonist, which sees him go from a depressed yuppie insomniac, to accidental thrill-seeking junkie, to acolyte of a violent cult in search of—to quote the writer JG Ballard—a “benevolent psychopathology”, recalls David Cronenberg’s adaptation of that writer’s own novel, Crash, from just three years prior. (A similar—albeit far less extreme—parallel has been drawn between by the filmmakers themselves to Mike Nichols’ The Graduate).

Panic Room (2002)

Fincher’s surprisingly straightforward thriller from 2002 was met with muted response at the time of its initial release, with many feeling it was a lightweight effort and a nifty excuse to try out some new camera tricks. Viewed now, it plays as a relentlessly tight and entertaining thriller of the kind we rarely get anymore, another example of the formerly overused but now dearly missed cliché “Hitchcockian”.

The claustrophobic setting and set-up are clearly meant to invoke Rear Window, while the roaming camera and continuous long shots recall Hitch’s other great one-set thriller, Rope. Fincher openly acknowledged these influences on his film, alongside John Huston’s great western noir tale of greed, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Sam Peckinpah’s brutal home invasion Straw Dogs (the latter, like Panic Room, often finds itself brought up in feminist discussion of cinema, albeit for very, very different reasons). Along those same lines, it’s easy to draw comparisons between Panic Room, the 1967 Audrey Hepburn vehicle Wait Until Dark, another shadow-drenched story of a woman squaring off with home invaders.

Zodiac (2007)

Along with being his masterpiece, Zodiac is also the Fincher film with the most overt connections to other films (at least up until Mank). There is, of course, Bullitt and Dirty Harry, both iconic San Francisco police thrillers which took inspiration from the real-life characters and events depicted in Zodiac (Fincher namechecks the former and shows the latter in his film). There is also Robert Altman’s magic realist serial killer tragicomedy Brewster McCloud, which likewise contains a character based on San Francisco detective Dave Toschi (played in Zodiac by Mark Ruffalo). Altman’s version is a pretty brutal sendup of the super cop as a phony, although Altman is probably taking the piss on Steve McQueen’s version of Toschi, rather than Toschi himself.

Then, of course, there is the 1932 horror adventure film The Most Dangerous Game, about a sportsman who hunts human beings on his private island. That film was thought to have possibly inspired the real-life Zodiac killer, and it serves as the centerpiece of the most frightening scene in Fincher’s film (arguably in his entire filmography). Given the presiding notion that the real killer had a movie fixation, it’s surprising that no one has looked into the possible connection between his crimes and a late, little-known (at least until its recent appearance on the Criterion Channel) Edward Dmytryk noir called The Sniper. That film sees a misogynist serial killer and sex fiend gunning down citizens across San Francisco while writing letters to the police and newspapers daring them to catch him. Needless to say, the parallels between it and the real history of the Zodiac killings make the already unnerving film even more disturbing in hindsight.

(On the subject of good film noirs to pair with Zodiac, there is also Fritz Lang’s When the City Sleeps, which splits its narrative between the inner office politics of a newspaper empire and the frantic search for a thrill-seeking serial killer.)

But the movie that casts the largest shadow over Zodiac, by far, is Alan J. Pakula’s brilliant account of the Washington Post’s investigation into Watergate, All the President’s Men. Fincher mirrors the obsessive, spooky and surprisingly funny mood and style of Pakula’s film (to say nothing of their similar period setting), and in so doing, he concludes his sneaky remake of the entire “Paranoia Trilogy”.

The Social Network (2010)

As with The Curious Case of Benjamin Button—which I’m skipping over because, quite frankly, I don’t find it very good or even interesting beyond its technical achievements—it’s a bit harder to find obvious connections between older films of the noir or noir adjacent variety and Fincher’s critically acclaimed Facebook origin story. However, the film does stretch at times into the domain of the legal thriller, and in so doing, brings to mind an unjustly overlooked film with which it shares a screenwriter: 1993’s Malice.

Cowritten by Aaron Sorkin and the great Scott Frank, and directed by mid-tier MVP Harold Becker, Malice is a heady amalgamation of legal, medical, serial killer, erotic and conman thriller. It contains some of Sorkin’s best-ever dialog—particularly wonderful are his contributions to a bravura deposition scene on par with those found in The Social Network—alongside some of Scott’s best-ever plotting. The end result is one of the most dizzying films of the ‘90s and one of the most purely entertaining movies you’re ever likely to watch, one that feels like the type of movie Fincher would have made if he were less of a type-A auteur and more of laid back journeyman.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011)

Fincher’s re-adaptation of the first of Stieg Larsson’s blockbuster Lisbeth Salander books didn’t have quite the same impact as the novels or even the original Swedish movies, but it remains an enthralling murder mystery for most of its runtime. It goes without saying that viewers left wanting more will always have the Swedish films, as well as the recent American reboot, The Girl in the Spider’s Web. Outside of those, they would do well to watch Insomnia (Erik Skjoldbjærg’s original, not Christopher Nolan’s remake), a similarly cold, morally murky serial killer procedural set amidst the icy wastelands of the Swedish countryside and featuring actor Stellan Skarsgard.

A more interesting pairing, at least thematically, would be with Robert Siodmak’s—the director most synonymous with film noir—late career return to his home country of Germany, The Devil Strikes at Midnight, about a German detective’s search for a serial killer during the Second World War. Like The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, the film draws an explicit connection between the evil committed by a serial murder and those committed by a nation in the thrall of Nazism.

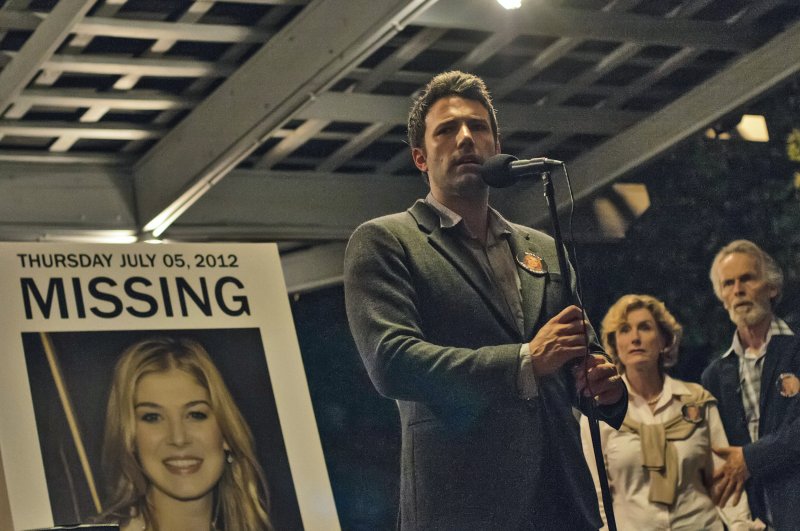

Gone Girl (2014)

Fincher scored the biggest commercial hit of his career (so far) with another adaptation of a best-selling thriller, Gillian Flynn’s domestic noir/missing person mystery Gone Girl. Like the original novel, the film is an enthralling deconstruction of the femme fatale, the film drawing upon the countless examples throughout cinema history—Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity and The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Rita Hayworth in Gilda and The Lady from Shanghai, Jane Greer in Out of the Past, Kathleen Turner in Body Heat, Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction, Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct, and many, many more (don’t sleep on Nicole Kidman in the aforementioned Malice)—to setup and subvert audiences’ expectations.

(Conversely, the pitch-perfect casting of Affleck’s sad sack charmer and suspected ladykiller brings to mind Cary Grant in an Hitchcock’s Suspicion.)

But if there’s one classic for which Gone Girl feels like a true spiritual successor, it’s John Stahl’s transgressively thrilling 1945 technicolor noir Leave Her to Heaven. Like Rosamund Pike’s Amy Dunne, Gene Tierney’s Ellen Berent is a possessive, calculating sociopath with whom we can’t help but sympathize even as she frames, murders and manipulates her way through life out of a misbegotten—but ultimately understandable—sense of love, as well as an admirable refusal to acquiesce to expected gender roles.

Mank (2020)

Fincher’s latest film takes looks a backstage (and highly speculative) look at the creation of the Greatest Movie Ever Made, Citizen Kane. There’s a fair amount of Citizen Kane in the DNA of The Social Network—both films are about the rise to power of a megalomaniac titans of industry driven by an insatiable need to possess something intangible, as represented by Kane’s sleigh Rosebud and Zuckerberg’s ex-girlfriend, respectively—so you could make a day-long film festival out of Kane, Mank and The Social Network.

Viewers will have plenty of films to supplement Fincher’s latest eve beyond Kane, as the filmography of titular hero, screenwriter and Herman J. Mankiewicz, as well as his rival/collaborator Orson Welles, are plenty stacked with both classics and deep cuts. For the purposes of this list, let me quickly recommend the romantic noir, Christmas Holiday, written by Mankiewicz (and directed by the aforementioned Robert Siodmak), to pair with Gone Girl, and The Trial, directed by Welles (from Franz Kafka’s novel), which would make an appropriately head-spinning double feature with either The Game or Fight Club.

Taken as a whole, I daresay this list of films should be enough to tide us over until Fincher releases his next movie, however long that might take.