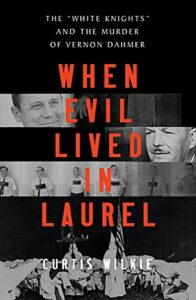

The people of Jones County had defied the confederacy during the Civil War, but by 1965, the KKK flourished, drawing its membership from both die-hard racists and those who saw the KKK as merely necessary for success in politics or business. The FBI needed someone ready to infiltrate the Klan, someone who would be accepted by them, but who had enough strength and integrity to resist them. What follows is the story of how Jones County everyman Tom Landrum came to join the FBI’s efforts to take down the Klan. Excerpted from Curtis Wilkie’s new book, When Evil Lived in Laurel (Norton).

___________________________________

Leonard Caves, the Circuit Clerk of Jones County, presided as something of a lord at the Jones County courthouse, where Tom Landrum, now thirty-three years old, worked as a county employee, counseling teenage boys who had run afoul of the law for violations such as shoplifting or petty vandalism. Landrum’s office was located in an annex attached to the old, pillared building where Willie McGee had died. The courthouse was a hive of activity where political gossip and rumors flourished, and much of the scuttlebutt gravitated around the office of the Jones County circuit clerk. It was a place where Landrum heard soliloquies of crude segregationist philosophies.

Leonard Caves, the Circuit Clerk of Jones County, presided as something of a lord at the Jones County courthouse, where Tom Landrum, now thirty-three years old, worked as a county employee, counseling teenage boys who had run afoul of the law for violations such as shoplifting or petty vandalism. Landrum’s office was located in an annex attached to the old, pillared building where Willie McGee had died. The courthouse was a hive of activity where political gossip and rumors flourished, and much of the scuttlebutt gravitated around the office of the Jones County circuit clerk. It was a place where Landrum heard soliloquies of crude segregationist philosophies.

Landrum was a frequent visitor in Caves’s office. The two men were about the same age and had known each other for years, a friendship built on their experiences teaching and coaching at schools in Jones County when they were just out of college. They engaged in small talk about the weather or sports or in speculation about political comings and goings. Caves seemed consumed by politics, and Landrum was amused by his behavior as a candidate. Caves would carefully dress in a starched white shirt and necktie, adorned with a dark suit, before setting out for door-to-door campaigning. Turning on the heat in his car in the midst of the Mississippi summer, he would sweat profusely to achieve the desired effect. Before leaving the car for house calls he would loosen his tie to give the appearance of a hardworking man, burdened but nonetheless willing to extend himself to reach out to voters.

Caves had no apologies for his zeal, and he frequently lectured Landrum on the art of politics. “Tom,” he said, “I know you’re interested in politics yourself, and there are things you need to do to succeed.” One recommendation was to embrace the Klan.

Even as federal power seemed to be closing in on Mississippi, the Klan in Jones County had been adding to its rolls. Hundreds had joined and Caves appreciated the organization’s strength. “There’s a lot of votes out there,” he told Landrum. “A lot of good men, respectable men,” he said of the membership of the White Knights. “If you want to make it in politics, it’s important to befriend these people.” They could deliver more than their own votes, Caves said. The numbers increased when they were able to convince family members and friends to rally behind candidates quietly endorsed by the Klan. The organization could make the difference in close local elections where no more than a few thousand people voted. According to Caves, the Klan’s support had helped elect the current mayor of Laurel, Henry Bucklew, because the Klansmen liked what they heard from him when he was a candidate. Caves wanted to ensure that he, too, had locked up Klan votes when he ran for reelection.

He hinted to Landrum that he had gone beyond the role of political supplicant and actually belonged to the White Knights himself. More than once, he encouraged his friend to join the group, not necessarily to wage war on local Blacks but to forge personal associations that would be politically helpful in Jones County. Landrum was not persuaded and gently declined Caves’s overtures. He did not tell Caves of his unhappiness over the violence in Jones County or that he abhorred the Klan.

*

In the middle of July 1965, another man made a very different approach to Landrum. Bob Lee, an FBI agent assigned to the bureau’s Laurel office several years earlier, was a regular visitor to the courthouse. As a native southerner—his formal name was Robert E. Lee and he had served as a highway patrolman in South Carolina before joining the FBI—Lee’s presence was acceptable to the county officials in Jones County. By this time, he was considered something of a local guy himself and not part of the greatly resented FBI task force of outside agents sent to the state the year before. He moved easily among the courthouse personalities.

Lee often dropped by Landrum’s office when in the building. He liked to keep track of youthful troublemakers. After completing college and coaching for a few years, Landrum had talked with Lee about the possibility of becoming an FBI agent himself. He dropped the thought after being told that a law degree was probably necessary, even though Landrum’s formal education was richer than that of most Mississippians.

Though no longer hopeful of becoming an FBI agent, Landrum developed a friendship with Lee. In his position with the Youth Court, he often talked with Lee about cases that might require formal referral to the FBI. Occasionally they touched on current events in Jones County involving racial violence. From their conversations, Lee recognized Landrum as a sensible fellow who had genuine concerns about his youthful charges. It also seemed clear to the FBI man that Landrum was disturbed by the influence of the Klan in Jones County. He heard Landrum openly deplore an outbreak of arson in Black neighborhoods that he attributed to the Klan.

The day after several Black families’ homes were shot into by night riders, Lee felt comfortable about mentioning a sensitive subject. Pulling his chair to sit closer to Landrum in the small courthouse office, Lee told him of his difficulty not only in combating the violence but in finding good men to take on an assignment that would help.

“Tom, you know we need to penetrate the White Knights,” Lee said. “They’re running amok around the state, causing all sorts of trouble. They’re a bunch of bullies, picking on poor colored people. They think nothing about burning down a house or a church. Look what they’re doing here in Jones County. They’re a bunch of sorry bastards. They’ve killed innocent folks. They’re ruining the reputation of Mississippi, Tom, and they’re destroying our own little community here.

“My job is to try to learn as much as I can about Sam Bowers’s operation. Now you know the FBI’s not here to protect the folks involved in civil rights work. That pisses off some of their workers. They think we should serve as their bodyguards. They don’t understand that our job is to collect as much information as we can about the Klan. We’re here to investigate, not to protect anybody. But we are especially interested in breaking up the White Knights. Our job is to investigate them, come up with good information, and turn it over to prosecutors to put them out of business.”

Landrum nodded. He seemed interested, so the FBI agent continued. “Tom, what we’re looking for is people we can trust to work with us. We’ve got some paid informants already, men who are in the Klan, and they tell us things. But we can’t always trust them. Some of ’em are in it just for the money, and in some cases, they’re likely to give us bum information or stuff that’s totally bullshit.

“What we need is somebody we can trust,” Lee said. “I know you know a lot of people around Jones County. Do you know anybody who might be willing to help us?” He paused. “Would you be willing to work with us?” Lee’s use of the word “trust” resonated with Landrum. As Lee made his appeal for Landrum to aid the FBI by joining the White Knights, the idea began to sound like a civic duty. It also offered a touch of adventure, for Landrum was still a young man. But he knew he had responsibilities that might prevent him from volunteering—a wife and five children and a home a few miles from Laurel that required regular maintenance to shelter his growing family.

“I don’t know,” Landrum replied, searching for a proper response. “It’s something I have to think about.” He was not prepared to rush into an arrangement with the FBI. He needed to talk with his wife and other members of his family. But he was intrigued. Instead of dismissing Lee’s call for help, Landrum told him, “Let me get back to you.”

When he left his office that afternoon, Landrum was already thinking, Somebody needs to do something. Bob Lee’s request called for an enormous personal decision, and it was not one Landrum could make alone. He would never dare take any initiative without consulting with his wife, Anne. She had matured from the winsome girl on the school bus to the mother of their five children, and she deserved to be heard on anything that could change their lives. Besides, he recognized her good judgment and often deferred to her.

After their children were asleep that night, Tom told his wife about Lee’s visit. The assignment held potential for disaster. Spies were executed, even in civilized countries. Landrum would surely be confronted with dire consequences if he were discovered to be a traitor in a band of lawless men. But as the couple talked, they also considered the possibility that had been presented to Tom to make an impact, to reduce the violence and restore some peace to Jones County. Anne felt instinctively that he should do it.

Before reaching a conclusion, however, they both knew there was one other person who should be brought into the discussion—Anne’s mother, Gertrude Geddie, a no-nonsense woman whom Tom looked on as a second mother. A few days later, the Landrums assembled their children and packed for a trip to meet the older woman the family called “Gert” for a weeklong expedition to the Florida Panhandle. The trip had the appearance of a vacation on the Gulf Coast, camping out at facilities at Fort Pickens, not far from where Tom had served in the air force. But it was also a retreat for them to thrash through the arguments—pro and con—regarding the call from the FBI.

They played in the weak surf, sunbathed, and took pleasure in late afternoon visits to a sno-cone stand. In the evenings they withdrew to their rental quarters, washed the sand from their children, and settled down for a late dinner while the children slept.

As the discussion about the Klan began among the adults, Gert set the tone. “First,” she said, “we have to pray.” Like many Mississippians, the family members were Southern Baptists and were uninhibited about practicing their religion. They prayed for guidance. They knew that by joining the White Knights, Tom might be publicly identified as a consort of men committing unspeakable acts. Yet by doing so, he might be in a position to provide the FBI with valuable information—even though there might never be any official recognition of the risk he took. If he were found out, he could be killed. Terrible things could be visited on his family members. Those fears were mitigated by something like a spiritual calling, a belief in seizing the rare opportunity to do good.

Landrum was inclined to take up the offer. He harbored contempt for the Klan and derisively referred to them as “kluckers.” The family weighed the perils and the rewards, and then Gert told her son-in-law, “You have to do it.”

The Landrums returned home, and Tom called Bob Lee.

*

The next evening, Landrum met secretly with Lee and another agent, Don Schaefler, one of the FBI newcomers sent to the state. On the pretense of car trouble, Landrum borrowed a friend’s unrecognizable Dodge to drive to Lee’s house, where he and the two FBI men hammered out an understanding. Landrum’s code name would be “Jackie.” Lee was to be called “Mr. Young,” and Schaefler “Adam.” Landrum was expected to give frequent written reports to the FBI, detailing the activities of the White Knights. He was given a special telephone number for the Laurel FBI office but instructed not to call unless an emergency arose.

Landrum was told that the only ones other than his own family who would know about his commitment were Lee; Schaefler; Roy K. Moore, the FBI special agent in Jackson in charge of Mississippi operations; and J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI director in Washington.

Though it had been rumored during the Neshoba County investigation that the FBI was making significant payments to informants, Lee did not offer Landrum money and Landrum did not ask to be paid. The FBI agreed to reimburse him for modest expenses and to use a government scale to determine payments for mileage when he used his car.

Landrum had one special request. He asked for a letter from Hoover, the nationally renowned crime-fighter who had led the FBI since its inception in 1935, something that would document the legitimacy of his work for the FBI. Landrum wanted it for posterity, to be able to show to his children when they were grown, or to be able someday to reassure law enforcement officials or friends that he had joined the Klan for a positive purpose. Lee agreed to the letter, but his Washington headquarters was unwilling to issue it. Lee was told that the bureau feared Landrum might write an unauthorized book about his experiences. J. Edgar Hoover was very possessive of his image. The director wanted no wildcat books, no stories that did anything other than burnish his reputation and that of his empire.

_________________________________________