Leonardo da Vinci painted La Giaconda, the Mona Lisa, in 1507, but it was not widely hailed as a masterpiece until the mid-nineteenth century, according to the historian James Zug, who appeared on NPR’s All Things Considered in 2011 to tell the story of how the most famous painting in the world achieved its celebrated status.

How did it become so well-known, so ubiquitous? It was stolen. It was brazenly, cleverly stolen from its wall display in the Louvre on Monday, August 21st, 1911. According to historians Dorothy and Tom Hoobler in their book The Crimes of Paris, no one even noticed that it was missing for twenty-eight hours. Once it was reported missing, sixty detectives began to hunt for it, and crowds gathered outside the museum to learn if it had been located. “French Public Indignant,” a New York Times headline read. “Affair Regarded as National Scandal.”

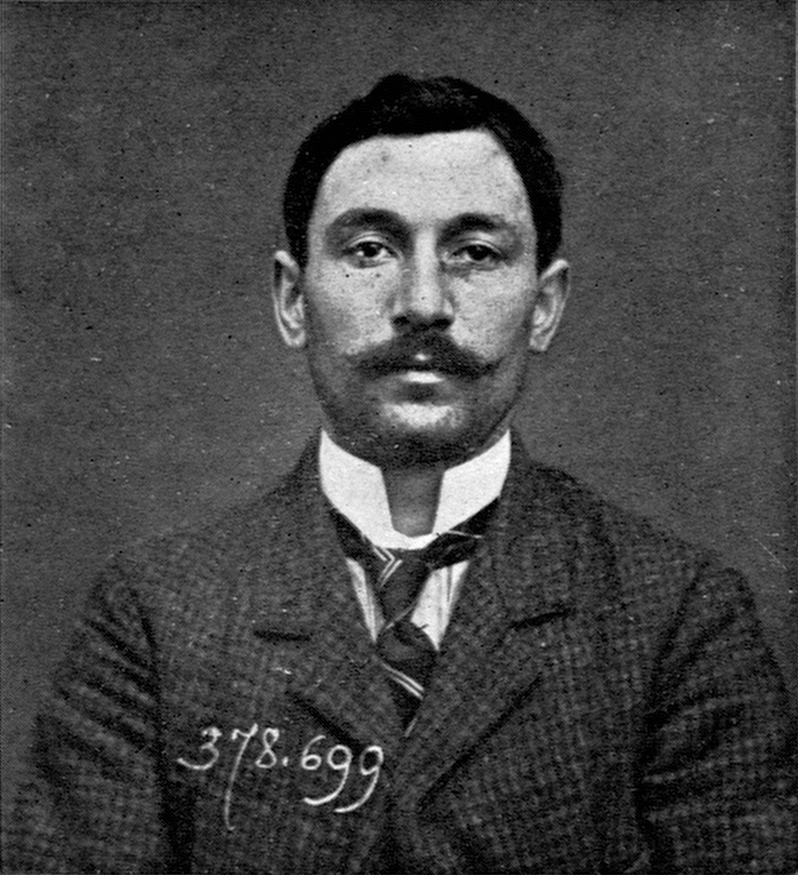

The painting had been stolen by an Italian immigrant—Vincenzo Perugia (sometimes spelled “Peruggia”), a handyman who had previously installed glass cases around the artworks at the Louvre about a year prior. Perugia claimed that he had arrived at the museum early in the morning on Monday, entering with a group of smock-clad cleaners and workmen. It’s also speculated that he might have stowed away in the supply closet the previous night. He made his way through the galleries, quietly ripping off the protective glass case that enclosed the Mona Lisa—likely a case that Perugia had himself installed. Simon Kuper at Slate notes that he removed the painting from its frame and slipped it under his smock, leaving the frame and glass case in a stairwell.

The painting had been stolen by an Italian immigrant—Vincenzo Perugia (sometimes spelled “Peruggia”), a handyman who had previously installed glass cases around the artworks at the Louvre about a year prior. Perugia claimed that he had arrived at the museum early in the morning on Monday, entering with a group of smock-clad cleaners and workmen. It’s also speculated that he might have stowed away in the supply closet the previous night. He made his way through the galleries, quietly ripping off the protective glass case that enclosed the Mona Lisa—likely a case that Perugia had himself installed. Simon Kuper at Slate notes that he removed the painting from its frame and slipped it under his smock, leaving the frame and glass case in a stairwell.

Perugia arrived at a locked door, and began to remove the doorknob when he was stopped. An affable plumber named Sauvet asked what he was doing, and Perugia casually told him that he was attempting to exit, but could not because the doorknob was missing. Sauvet offered to help, and using some pliers, jimmied open the door.

Zug notes that Perugia’s exit would have been rather conspicuous; not only was he exiting a closed museum, but he also happened to be out and about, early on a Monday morning—an interval during which Paris was usually desolate, given the large number of people inside reeling from the hangovers caused by Sunday night parties. Despite his odd behavior, perhaps it is because there were few people on the street that he was able to hurry undetected to a station two kilometers away and across the river in Quai d’Orsay, where he boarded an express train at 7:47 a.m., out of Paris. A bystander on the street saw a man in a white smock throw away a doorknob, but through nothing of it at the time.

The painting wasn’t officially declared missing until the following afternoon. An artist named Louis Béroud who enjoyed setting up an easel in the museum had noticed right away that the Mona Lisa was gone from its display, but since the Louvre had begun an ambitious feat of photographing all their artworks, which required removing the paintings individually and bringing them to the roof to be captured (due to camera technology of the time, could only be done outside), and he had assumed that it was the Mona Lisa‘s turn. But he had planned to sketch her, and couldn’t seem to work without it, so he asked a museum guard, Paupardin, when it would be returned. The guard didn’t know. But Béroud insisted that he ask. The photographers told the guard that they had not taken it up, and the guard returned, dumbfounded.

When the Louvre declared that the painting had been stolen, the museum shut down for a week. The nation was outraged. Dorothy Hoobler informed NPR that there had been ire mounting in France about American millionaires who seemed to be buying up European masterworks, and conspiracy theorists wondered if the banker J.P. Morgan had been behind it. Others believed, noting the brewing tensions between European nations at this time, that Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II was behind it, somehow. The far-right publication Action Française thought it made more sense to blame Paris’s Jews.

Many suspected that the painting was still in the museum, somewhere. Sixty detectives were assigned to look for the stolen masterwork, and many amateurs (whom the Times styled “amateur Sherlock Holmeses”) began to hunt as well. But the lead detective on the case was Alphonse Bertillon, who had a reputation as being a real-life Holmes.

The painting, itself, had been stashed under a false bottom in the trunk in Perugia’s Paris boardinghouse. Prior to stealing it, Perugia had hoped the sell it, but as soon as the frantic press coverage began, he knew there was no chance of making a quiet deal. Meanwhile, after a week, the Louvre had reopened. A throng of people, which included Max Brod and Franz Kafla, hurried into the museum to view the empty place on the wall where the Mona Lisa had once hung.

On September 7th, the police arrested their chief suspect: the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, whom they believed had also stolen a number of statues from the Louvre. The Paris police had bungled lots of the investigation thus far (including not being able to match a fingerprint that Perugia had left on the frame to the ones in his two previous arrest records, because Bertillon had insisted on cataloging fingerprints according to his own system rather than by fingerprint patterns, as was accepted), and were eager for a win.

That month, a Belgian traveler named Honoré Joseph Géry Pieret visited the office of the French newspaper Le Journal, and sold them an Iberian statue that he claimed he had stolen from the Louvre. He claimed to have stolen another statue and sold it to a painter who was a friend of his. When Géry visited Paris, he often stayed with his friend Apollinaire, a radical poet who had once demanded the Louvre be burned down. After Géry told his friend that he had stolen the statues he had been distributing, Apollinaire panicked and contacted his friend Pablo Picasso, who had two statues from Géry in his Montmartre apartment. On September 5th, Picasso and Apollinaire bagged the statues and lugged them out from his building, towards the river. They had planned to dump them, but when they stood on the embankment, they changed their minds.

A week later, Apollinaire was arrested for the theft of many items from the Louvre. He implicated Picasso. Slate notes that they both cried during their interrogations, and Picasso claimed a few moments later that he actually had no idea who Apollinaire was. Without more evidence, the police had to let them go.

Twenty eight months later, Perugia struck. He attempted to sell the famously-stolen painting to an art dealer named Alfredo Geri in Florence. The dealer asked him to leave the painting at his office, and shortly after Perugia went back home, he was met by police. He pleaded guilty to the theft, claiming he had been attempting to return pirated Italian art to its home country. Several others were brought in on suspicion of collaborating. According to Dorothy and Tom Hoobler, Perugia added during his interrogation that he had stored the painting with a friend, a student at Paris’s School of Hypnotism and Massage named Vincent Lancelotti, when Perugia’s apartment became too cold to keep the painting without fearing damage to the canvas. Shortly after the theft, the Paris police had recieved a tip that Lancelotti had the painting, and they searched his apartment, but nothing was found. Lancelotti’s mistress, Françoise Séguenot, passionately denied this right away, but Vincent’s brother Michele gave some information away. It was later revealed that both of the Lancelotti brothers had been with Perugia when he absconded to the train station, the morning of the theft, though Vincent had insisted this was merely a friendly gesture. It has been suspected by some that the brothers were involved in the actual theft, too, but this was never proven.

In the words of Tom and Dorothy Hoobler, all three were arrested on suspicion of “receiving and concealing an art object stolen from a state museum,” but only Vincent was held at a prison. It seems that the Italian government exchanged the painting for agreeing not to extradite Perugia, who was now regarded as a national hero. When Perugia didn’t return to France, charges against his alleged co-conspirators were dropped. Perugia spent about a mere eight months in prison, several months shorter than his sentence.

A few days after Perugia’s trial in 1914, war broke out. When he got out, he served in the army.