According to the FBI investigators who spent 12 years trying to track her down, Heather Tallchief and her lover committed “the perfect crime”…

__________________________________

Before she became America’s most wanted woman, Heather Tallchief moved to Las Vegas. It was 1993—the year of the World Trade Center bombing, the Rodney King trial, and Nirvana’s benefit gig for Bosnian sex abuse victims at Cow Palace. She was 21 years old and short on money, but the decision to leave San Francisco still surprised her family and friends. A charismatic poet, 27 years her senior, had bought her a drink at a bar a few months earlier, then read her tarot cards. It was decided that their future lay in the land of casinos. Their lives to date, in different ways, had been marked by losses. They wanted to start winning.

In Vegas, Heather made another out-of-character move: she applied for work as a driver of armored vehicles supplying cash to casinos. “She told us she wanted a career in the security industry,” said Mike Tawney, of Loomis Armored Inc, when interviewed by a British newspaper in 1997. “She said she wanted to start at the bottom, to learn the industry inside out.” In a profession dominated by bulky white men, she stood out. She was modest and beautiful. She had a good line in cutting comments and knowing smiles. She had no relevant experience, but she passed the criminal record check with a clean bill of health. Her references were perfect.

Medicine and caregiving had been Heather’s passions up until that point, along with an interest in ancient Mexican art and Mayan ceramics. Before the Vegas move, she’d worked as a nurse at a San Francisco AIDS hospice called the Kimberly Quality Care Center. They were sorry to lose her. “She was a great worker,” a senior Kimberly nurse recalled. “She had this amazing empathy with patients; even the ones closest to death would be smiling when she left their bedside.” But in the 14 months Heather worked in the hospice, she saw many patients die, some of whom she had become close friends with. “She began to wonder why she couldn’t be happy, have nice things,” according to Ann Tallchief, her mother. “She said she didn’t want to worry about money, or people dying.” Heather had been looking after others for most of her life. When she was two years old, growing up in Buffalo, New York, her parents had divorced and her mother had moved to California. She’d been left in the custody of her father, a laborer, despite the fact he was battling drug and alcohol addictions and seemed at times not to want her around. His daughter’s upbringing was marked, he admitted by “two bad parents.”

At first, like most new drivers at Loomis, Heather was assigned to the casino house runs. This work involves transporting new banknotes to thousands of gambling tables each day, but the stakes to the company and the employee are relatively low. The new notes are easily traceable. The smartest thieves don’t want to hijack a vehicle on a house-run.

In her first weeks in her new job, Heather took a firing range test to qualify for a side-arm. She shocked her coworkers by achieving record scores. Then, in September, after proving her diligence and reliability on the house-runs, she was promoted to one of the riskier bits of work the business did: the cash machine runs. Five days a week, accompanied by two colleagues, she would drive millions of dollars in unmarked bills to the Strip.

She was known by then as an “ideal employee.” She didn’t talk much about her past—you’d get more information from the label on your average bottle of beer—but some colleagues knew she’d worked in nursing, and that seemed to make sense. She cared about other people. It was clear in her countenance, the way she spoke, her questions. She asked after their kids, their wives. Some of the drivers and cash couriers admired her from afar, and others convinced themselves they had become good friends with her. Some wanted her approval, others wanted more. They had the self-awareness necessary to see that she was out of their league, but not always the discipline to conceal their reverence.

She dealt with their comments about her beauty—a mix of Seneca Indian (her father) and Italian American (her mother)—with grace and patience, a self-deprecating joke or averted gaze, but it was also true that she began dressing as if hoping to limit the amount of eyes on her. It was as if she sensed her looks could be a problem for her plans.

At work she wore her hair tied back with a bow. Thick spectacles sat on her nose, despite her medical records—had anyone looked at them—evidencing 20/20 vision. Scott Stewart, a Loomis courier who worked with Heather at the time, recalled her choice of footwear. Every day she wore “a rugged work boot-type thing,” he said.

Heather’s only break from this sartorial habit came on the day of her disappearance: October 1, 1993.

* * *

The 1st was a Friday. The Strip was gearing up for the weekend influx of out-of-town gamblers, the addicts and bankers and bachelor parties, people whose moral compasses would be as vulnerable as their wallets. Weekends were also full of “whales.” Customers who, if you were lucky enough to catch them, would net your casino meaningful money.

On this particular Friday, the one that would go down in the history of Las Vegas’s greatest heists, Stewart and another man were responsible for couriering cash to casino ATMs. Heather was behind the wheel. The truck was filled with neat piles of crisp, unmarked notes amounting to around three million dollars.

Heather didn’t seem particularly tense that morning, in Stewart’s later recollection. But her footwear did strike him as out of the ordinary. “That particular morning, she had a dressier shoe on,” he said. “At the time, we just thought maybe she was going out to dinner or something after work and needed to get changed quick.”

It was going to be a long day. They all knew that. Heather, the “ideal employee”, had made a point of being familiar with convention schedules and check-out times for the big hotels in the area. She knew that October 1st was going to be one of the biggest “change over” days of the year—a point in time when the resorts move from hosting one convention to another. Traffic, human and vehicular, is at its heaviest.

It was around 8 a.m. when the armored vehicle driven by the young woman in the delicate dress shoes pulled up to the Circus Circus casino. The Circus Circus is part of a resort which offers “a fun-filled, all-ages Las Vegas adventure at an affordable price.” It was the first stop of the day.

Moving money around the Strip was hard, heavy work. Stewart and his partner hauled the first of the money containers out of the truck. Following protocol, they closed the truck doors, made sure they were locked, and then slapped the truck’s flank to let Heather know, in the absence of available parking nearby—“change over” day—that she should start driving over to the other side of the casino and wait there as best she could.

Stewart and his partner followed a simple route through the casino. It would take, if all went well, around 20 minutes. “It was basically like a point A to point B,” Stewart has recalled. “We would start at one ATM and just work our way through until we got to the last one. And at that last one was the exit to where Heather was supposed to pick us up.”

But when they got to the exit, on schedule, the armored truck was nowhere in sight. Nor was there any sign of Heather.

Stewart and his partner waited, then waited some more. And then, they began to get worried.

Maybe she’d got lost, or stuck in traffic?

She and her vehicle, and approximately three million dollars in cash, had disappeared in the kind of daylight which reporters, the next morning, would call broad.They waited a few minutes more. They liked Heather. They didn’t want to get her in trouble by prematurely reporting her absence to the office. But then they started wondering if there might have been a serious accident on the road. What if Heather was badly hurt? What if she’d even been kidnapped? Just three years previously, a famous heist had occurred on an armored vehicle transporting money to a Federal Reserve branch in Buffalo, New York, where Heather was from. The drivers in that case had stopped for a sandwich, then someone had stuck the barrel of a gun into a slot in the door. A female guard was held at gunpoint. Loomis employees, in the wake of this and other incidents, received training in what to do in an emergency.

Stewart and his partner finally placed a panicked call to the Loomis office. A fresh armored vehicle was sent out in a rush to pick them up.

“Given the technology of the time,” Stewart said later, “there was no tracking, there was no GPS, basically all we had was a radio.”

In the new vehicle, as they conducted a sweep of the streets, looking for their original truck, they tried desperately to make radio contact with Heather. But she and her vehicle, and approximately three million dollars in cash, had disappeared in the kind of daylight which reporters, the next morning, would call broad.

* * *

Last month I tracked down an out-of-print book I have wanted to read for a while. The title is Hijacked. It’s a collection of poems by a writer named Pancho Aguila. Like the story of Heather Tallchief as I’ve come to see it, Aguila’s poems are full of wants—the desire for intimacy, reinvention, excitement, freedom—and of what it feels like to be wanted in a different way, by the law. The book was printed in 1976 by Twowindows Press in Berkeley, in an edition of only 350 copies. One of these first editions arrived at my apartment in clean brown wrapping paper neatly affixed on three sides by two-inch pieces of Magic Tape.

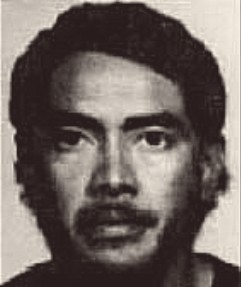

My interest was extra-literary. “Pancho Aguila” was one of several pseudonyms used by Roberto Solis, who wrote the poems in jail after being convicted of murdering a security guard during a robbery in 1969. Solis was a handsome man. Charismatic. Well-read. Thoughtful. He was a convincing talker who’d expressed remorse for what he’d done in his youth, and his poetry caught some attention during his long sentence. He had one poem published in the American Poetry Review and, when he came up for parole in the early 90s, wrote letters of support to the board, citing his contribution to American letters as relevant evidence that he had been reformed. Solis was given parole in 1992. By that time, he had a tattoo on his right forearm bearing the words Esta Vida Loca. He went to Europe, but soon ran out of money and returned to California. Shortly thereafter, he met Heather Catherine Tallchief at a bar, and they went home together.

This crazy life. Heather would later claim that she moved to Las Vegas at Solis’s suggestion. That she applied to drive armored vehicles for Loomis at his suggestion, too. The FBI thinks he showed her how to apply for false identities in 1992, using ads in Soldier of Fortune magazine. By the beginning of 1993, it now appears, Heather had obtained “legitimate” drivers’ licenses in 12 different countries. These are useful assets for anyone who thinks they might, one day, need to flee into a foreign country. With a local driver’s license in an assumed name, one can apply for other forms of identification too. Apartments can be rented, jobs can be obtained, taxes can be paid. A new life can be born.

And yet, if the name Roberto Solis looms large in what we now know of Heather’s story and her secret life, it was not mentioned once in the initial reports of the missing Loomis millions. Nor did Solis’s poet pen-name, “Pancho Aguila,” receive a mention.

Digging around in the Nevada newspaper archives, I have found, from articles written in those crucial first days after Heather’s disappearance, paragraphs full of little more than consternation, guesswork, and appeals for witnesses to come forward with the sought-after facts. The first line of an article in the Elko Daily Free Press on October 4, 1993 provides a typical example: “A $25,000 reward has been offered for information leading to the capture of those involved in the theft of an armored car with $3.1 million in cash,” it reads. “Police said the 21-year-old woman was making the rounds with two male co-workers when she stopped the van outside the Circus-Circus … The FBI has launched a search in the Southwest for the woman and van.” A police lieutenant named Kent Bitsco is quoted in the article as saying: “The investigators are still trying to put the pieces together.”

The archives of the Reno Gazette show them picking up the story the next day. Sergeant Larry Duis of the Las Vegas Metro Police told a writer there: “We’re getting a ton of leads, the normal run of crazies, and a couple of sightings, but nothing that’s able to satisfy us.” But he did share his personal hunch that Heather, if she was somehow implicated in the mission millions, had been accompanied in the crime by someone with a less-perfect record. “This is too big for anyone to have acted alone,” he said. “It’s possible she’s a victim. I’m not sure too many people believe that, but it’s a possibility.”

Both Bitsco and Duis soon proved themselves to be correct in most respects. The FBI, conducting a sweep of Heather’s apartment, were about to find a crucial piece of evidence: a fingerprint that matched a record in their database.

The print belonged to a man who they believed was named “Gabriel Suave.” The federal warrant they put out on October 7, alongside one for Heather, was issued in this name. But Gabriel Suave was a pseudonym, the authorities would soon discover—one of many identities adopted by a 48-year-old armored car robber, convicted murderer, and acclaimed prison poet who’d once chaired the Creative Writer’s Workshop at Folsom Prison, and who published work as “Pancho Aguila.” The very same man who had made parole last year and who, in the first edition of Hijacked that arrived at my home last month, authored the following lines about love, and drama, and wanting:

And I wait

In my prison cell

Thinking true romance

Watching every channel

For my cinderella

Whose time has not come

To throw me pumpkins

Nor I

To offer

A high-heel crystal shoe

Underneath a moon of cheese

The rats have left behind

In the hollywood night

Roberto Solis gave the poem from which the above lines are taken the title “TV Romance.” It’s as if he foresaw that the heist he would commit with Heather, nearly two decades later, would contain details that would seem scripted for the screen. The “crystal shoe” that brings to mind Heather’s footwear on the day she disappeared. The idea of her as his “cinderella” in waiting, “whose time has not come.”

Roberto Solis

Roberto Solis

When Solis wrote these lines, Heather was 4 years old, living in Buffalo, New York, watching her father struggle with drug and alcohol abuse, and receiving occasional letters from her mother in California. She must have felt, at times, that no-one on earth wanted her.

* * *

Every couple in love needs a place to live. The apartment Heather shared with Roberto Solis in Las Vegas was just east of the Strip. In an article in the Elko Daily Free Press, from October 7, 1993—6 days after the disappearance of the truck and its estimated $3 million in unmarked notes—a woman who managed the apartment building told the newspaper that Ms. Tallchief and her older boyfriend were “very private.”

She would “go out to the pool and swim a lot,” the manager said, “and everyone would talk about how pretty she was. But he never hung around the front. He always used the back stairs.”

A man named Walt Stowe had by then been assigned to the case as the FBI assistant special-agent-in-charge. He began to pursue a lead indicating that the couple may have fled to Mexico. Travel records suggested they had visited the country just a few months before their disappearance.

Then more information supporting this theory emerged. Stowe discovered that, a few days before the heist, Heather and Solis had told the manager of a local business that they were soon planning to move to Mexico permanently. They gave the guy a business card, in fact. It was for a company called Tek-Si Consultants in San Ysidro, California, and it was accompanied by a forwarding address where they could be reached via a post office box in San Diego.

Stowe checked out these addresses, and reached out to legal attaches in Mexico, hoping that Heather and Roberto Solis had slipped up by leaving evidence of their plans behind. Even the very few people on earth who are capable of carrying out “the perfect crime,” as this one was already being called, sooner or later end up making mistakes.

But Stowe soon came to the conclusion that the couple, as part of their meticulous planning for the heist, had been deliberate about everything. The addresses they’d left behind were red herrings, false information intended to waste the FBI’s resources and buy the couple just a little more time to disappear elsewhere, perhaps into Europe. Several art magazines with pages ripped out had been found in the apartment. Perhaps they were posing somewhere as art dealers, or perhaps this was just yet another false lead.

Weeks passed, and the FBI began to sense that this was a case that would take time, a lot of time, to bring to a conclusion.

Four years after her disappearance, Heather Tallchief rose to #3 on the FBI’s list of its ten most sought-after fugitives, the highest position occupied by a female felon in 23 years.They were correct. Four years after her disappearance, Heather Tallchief rose to #3 on the FBI’s list of its ten most sought-after fugitives, the highest position occupied by a female felon in 23 years. When such prominence is afforded to a fugitive, information tends to follow, but in this instance they still received few meaningful leads. Heather Catherine Tallchief had obtained the dubious distinction of becoming the “most wanted” woman in America, but she remained as elusive as ever. The FBI marveled at the level of planning and standard of execution that lay behind the heist. They couldn’t help admiring her—even liking her, just a little. They began to piece together the facts of what Heather done, but they still struggled to understand who she was, and where she’d gone, and these mysteries elevated her in their minds. “I’m not going to bad-mouth somebody I haven’t caught,” FBI Agent Burk Smith told a reporter for the Calgary Herald in 1995. But even as he tipped his hat to her skill, he expressed doubt as to how long the seeming excitement of making off with millions of dollars might last. Heather, wherever she was, would forever be looking over her shoulder. “Would you want to live that way?” Smith asked.

One possible last sighting of Heather did emerge, but it seemed at first like a long-shot. At an airport in Denver, several hours after Heather had vanished in Las Vegas, two workers saw a man dressed as a doctor pushing a wheelchair towards a waiting limousine. The woman in the wheelchair, her face mostly covered, at first seemed elderly and infirm, but when she got up and climbed into the limo she did so with a speed and dexterity that struck the two witnesses as strange.

* * *

Here’s what we now know happened.

In the second week of September 1993, in preparation for the events of October 1st, Heather donned a nurse’s uniform, playing a role she knew well. She pushed a wheelchair bearing Solis, who was disguised as a wealthy, aging gambler, onto a chartered Lear jet at Las Vegas airport. It was a dress rehearsal, or an attempt to establish a pattern, and it went off without a hitch, so Heather booked a second flight out of Las Vegas. It would leave on Friday, October 1st, late in the morning. For this second journey, they could swap roles. People would be looking for Heather after the truck went missing, but no-one would be searching for a man, even one who looked like Roberto Solis, pushing an elderly lady along.

Around this time, the FBI eventually discovered, Heather took a lease on a garage under the name “Reinforced Steel,” which, using a false name, she’d registered as a business for the building and repairing of armored cars. This way, if a Loomis truck somehow ended up driving into the garage on October 1st, no-one would be overly suspicious. Heather, or Solis, had business cards for the company made in the names of Nicole Reger and Joseph Panura.

On September 28th, Heather wrote a letter to her mother, apparently expressing regret at their recent estrangement. Instead of mailing it, she left it to be found in the Las Vegas apartment she shared with Solis. She wrote in the letter that it was doubtful she would ever see her mother again, but told her “not to fret,” for “we have never been true friends.”

On October 1st, after she dropped off her colleagues at the Circus-Circus Casino so they could deliver the first batch of dollars to the ATMs inside, Heather drove, not to the casino’s front entrance as arranged, but to the “Reinforced Steel” garage she’d rented a few minutes away, at 708 South First Street. She parked the vehicle in the garage, where Solis was waiting.

The Circus-Circus Casino, Las Vegas.

The Circus-Circus Casino, Las Vegas.

In the garage, Tallchief and Solis hurriedly packed the cash into boxes and suitcases using materials they’d already bought and placed there. Then they began disguising themselves. Tallchief dressed as an old woman, Solis as a doctor. The evidence of their activities that day would not be discovered until two weeks after the crime, when the owner of the garage grew concerned that he hadn’t seen his tenants for a while. He entered the premises and found a Loomis van fitting the one the FBI were seeking, then called the police. At the scene, investigators retrieved the vehicle and gathered other evidence left behind: $3,000 in $1 bills; numerous packing materials; phone numbers to businesses in Miami, the Grand Bahamas, and the Cayman Islands; mail rates; and information on yacht charters.

At 11.20 a.m on the day of the crime, Heather and Solis arrived at Las Vegas airport. In his white doctor’s coat he pushed his elderly patient into the private charter area, where they’d boarded their rehearsal jet just a few weeks earlier. They carried, according to the pilot, only one suitcase, and one box. This supported the FBI’s theory that the couple had arranged, perhaps through a courier pick-up service at the garage, for a big chunk of the heist money to be sent by mail to unknown addresses elsewhere.

At 11.32 a.m on October 1st, Heather’s plane sped along the runway, destined for Denver. As it ascended into the sky, staff at Loomis were just alerting the Las Vegas Police Department to the fact that one of their employees might have been abducted.

“We thought for sure we’d find her body out in the desert,” Sergeant Duis, of the LVPD, admitted in 1997. “Maybe with the burnt-out truck alongside.” Then he added: “I hope there aren’t too many like her out there—we rely on our criminals to be dumb.”

“I hope there aren’t too many like her out there—we rely on our criminals to be dumb.”For a total of twelve years, the FBI searched for Heather, or her body, and found few meaningful leads besides the discovery of an abandoned wheelchair in a Denver motel room. It was a rare file for the FBI—“something totally different,” Agent Burk Smith admitted to the Calgary Herald in June of 1995, “because of the sophistication, the planning.” The agency felt that Tallchief had become “a master of disguise,” and they worried that the distinguishing characteristics they had on file for her might not be sufficient to attract eye-witness matches: 5 feet 8 inches tall, about 130 pounds, with a pierced right nostril, 13 earring holes in her left ear, and “a tendency to grind her teeth in her sleep.”

And then, just as the FBI were giving her up her ghost, Heather walked back onto the public stage in dramatic fashion.

* * *

On September 12, 2005, almost exactly 12 years after she’d disappeared, a woman in her early thirties, her features slightly broader than before, her eyes a little less lively, boarded a plane from Amsterdam to Los Angeles. Heather was traveling using a British passport she had obtained under the name Donna Marie Eaton. She was about to stun the United States Marshals Service in Nevada by surrendering herself into their custody.

Fidencio Rivera, then the Chief Deputy U.S. Marshal in Las Vegas, told the Las Vegas Review Journal that Tallchief’s surrender came as a complete surprise to him. But for Heather’s part, it all seemed, once again, meticulously planned. She had hired a lawyer—Robert Axelrod of Meriden, Connecticut—who had worked on cases of fugitive surrender and Americans abroad before. He helped set up a press conference.

It was held just before she was taken into custody. A chance, perhaps, to frame the story early, and on her own terms. “She came here to admit her responsibility, to accept her responsibility and face the music,” Axelrod said. She was admitting to her role in the crime and pledging that she would pay back Loomis in full. Her first payment—which eventually amounted to $1,300—would be through money earned through the sale of photographs of her to the media reporting the case.

She was a mother now, she told those listening. Her son was 10 years old. She was tired of hiding, and making him hide. She didn’t want to live her whole life on the run.

The boy’s father was Roberto Solis. She’d become pregnant shortly after they’d absconded with the money, traveling to Denver, and then Miami, and then “beyond.” But Solis hadn’t treated her well, especially after the baby was born. He had moved other women into the home they shared. She began to feel it was best for her and her son if she ran away, and never looked back. She was good at that—at fleeing abusive men, and starting again.

She said she hadn’t seen Solis now for the best part of a decade. The money from the heist had been left with him, in her accounting of events. All of it except a small amount in cash she’d taken when she left with her baby son, to survive. She had no idea what he’d done with the millions, or where he was now hiding.

For a while she’d looked after her son by earning money as a prostitute. More recently, she’d been working as a chambermaid at a hotel in the Netherlands. She’d begun a relationship with a man whom she was happy with. Her son considered this man to be his father.

“It’s a lonely life, being a fugitive,” she said in her taped confession. “I certainly don’t go to book clubs and cake sales and stuff. I don’t have coffee morning with the girls.” After 12 years of lying to those she loved, and having no contact at all with her family, it was time to stop running. “If you’re living in a prison mentally,” she said, “then what is a box, a room, restricted privileges? It’s nothing compared to what I’ve already been through. I truly feel like I’m setting myself free.” If she expunged her own criminal past by serving her time, maybe she’d be setting her son free, too. He’d have a chance at leading a better life than she’d had. And he had now finally reached an age where he might understand, and do okay in the care of others. She could have turned herself in to authorities earlier, of course, but she knew what it was like to be a toddler left without a mother. At the age of 10, it might be different.

She reiterated that she had met Roberto Solis—then calling himself Julius Suave—at the age of 21. They were in a bar she was barely old enough to be in. He was more than twice her age, but he appealed to her. “I found him attractive as a man,” she said. “I would have never accepted a beer from him if I didn’t find him attractive.”

When she went home with him for the first time, she found he’d created a bizarre altar in his living room. There was a goat’s skull, candles, incense. He read her tarot cards. It was alarming on one level, but his spirituality impressed her. Growing up in a house full of drugs, and seeing her father using, she’d become a user herself. Cocaine, and crack cocaine. Alcohol. And here, in Roberto Solis, was a man who seemed to believe in something more than individual oblivion.

After they’d been together for a few weeks, he admitted his criminal past. He said he was changed. If only they could move to Las Vegas, he told her, he was sure he could beat the odds at the casinos and win them a heap of money. In the meantime, she should take a job to help them get by.

One day, she says, he brought home a job application for Loomis, which was searching for new drivers for its fleet of armored vehicles. It was a company that I’ve discovered that Solis must have had some familiarity with: Twenty-four years earlier, according to court papers, the failed robbery that had landed him in prison had involved a Loomis armored vehicle at a Woolworth’s store in San Francisco. With his accomplices, Solis had approached the vehicle’s driver, a father of six, and told him to hand over the bag he was carrying. But the bag, by then, was empty of cash. The man turned it inside out to demonstrate that the thieves were out of luck. When Solis saw this, he grew angry. He shot the man twice in the back, killing him.

A man’s voice, amidst increasingly strange sounds, would count from ten down to one. Then she’d wake up from what seemed to have been a deep sleep, remembering nothing.Solis had served time for his first crimes, and now it was Heather’s turn. After her press conference and FBI interviews, she pleaded guilty before Chief U.S. District Judge Philip Pro to one count of bank embezzlement, one count of credit union embezzlement, and one count of possession of a fraudulently obtained passport. She admitted to helping Solis to steal approximately three million dollars, but her defense attorney presented, for mitigation, the testimony of a psychiatrist who concluded that Solis had “brainwashed” Heather. It was said that he targeted her, that first night in a San Francisco bar, because she was pretty, but also because she was young. He soon realized she was vulnerable on account not only of her age but her upbringing. With a combination of “sex magic” and hypnosis, the defense claimed, he overrode her everyday judgment.

It was said that every morning, before she went to work, he would play audio tapes to her. A man’s voice, amidst increasingly strange sounds, would count from ten down to one. Then she’d wake up from what seemed to have been a deep sleep, remembering nothing. It was possible he had convinced her to take part in the robbery while she was in this suggestible state, but the prosecution introduced expert testimony to counter this version of events, stating that the more likely motivation for the crimes was greed and the desire to please her romantic partner, motives which it said were common to many offenders.

* * *

On March 30, 2006, Heather Tallchief was sentenced to 63 months in federal prison, which was the maximum sentence under the limited charges the prosecutors had decided to bring. She was also ordered to try and repay, over the remainder of her life, $2,994,083.83 in restitution to Loomis or its insurers. She was subsequently released from prison in the summer of 2010. She keeps a low profile, understandably, and is thought to have been reunited with her son. She has not granted any interviews and, at the time of writing, attempts to reach her through her legal representatives have failed. Perhaps she is still, as the FBI described her, a master of disguises. Maybe she always was. A few weeks ago, I tracked down an old high school classmate of Heather who had never spoken about their friendship before. She sent me scanned pages from the 1988 yearbook for the Buffalo Academy of the Sacred Heart, where she and Heather were once students. Under a black-and-white photograph of Heather posing on some steps, the caption reads: “A genuine uniqueness and an extraordinary sense of personal style radiates from sophomore Heather Tallchief as she expresses her ability to contrast colors.”

Roberto Solis, and the missing millions, have never been found. If he is alive, he would now be 74 years old. The first line of the “Remarks” section of his FBI “Wanted” poster states: “Solis enjoys writing poetry.” Perhaps the authorities hope he is still writing, under one name or another, and that a publication, a particular turn of phrase or image, might eventually give him away.

“Pancho Aguila,” Solis’s first literary pseudonym, is still listed in Poets & Writers’ Directory of Writers. I haven’t been able make contact with the person named Esperanza Farr who is listed as his literary representative in San Francisco, but presumably the FBI has tried sending her a fan letter. Records I have found suggest that Solis’s mother went by the name Esperanza Silva at the time of her son’s disappearance, and was living in San Francisco. Perhaps these two Esperanzas are the same person.

Under “More Information” in the Poets & Writers listing, the following additional insights into Roberto Solis’s alter ego, Pancho Aguila, are provided:

Gives readings: No

Travels for readings: No

But as with almost everything in the story of Heather Tallchief and Roberto Solis, it’s hard to know where the line between fact and fiction lies, and when a ghost might decide to reappear.