Around seven thirty on the evening of Thursday, September 14, 1922, two nights before Edward Hall’s body was found beside an unidentified female corpse, on a lover’s lane outside of New Brunswick, New Jersey, the phone rang at 23 Nichol Avenue, a Victorian mansion where Hall had lived with his wife, Frances, for a little more than a decade. One of the couple’s maids, twenty-year-old Louise Geist, paused her work in a bedroom on the second floor and scurried across the hallway to answer the call. A woman on the other end of the line asked for the reverend.

“Is that for me?” Edward called out from the bathroom.

“Yes,” Louise replied.

“I’ll be out in a minute.”

Louise went back to work, though she couldn’t help but overhear Reverend Hall’s side of the conversation.

“Yes . . . Yes . . . Yes . . . That’s too bad . . . Yes . . . Couldn’t we make arrangements for about eight fifteen? . . . Goodbye.” Click.

Before long, Edward came down and put on his coat. Frances entered from the porch. “I am going to make a call, dear, and will be home soon,” Louise heard the reverend say. She passed through the kitchen and went out onto the back stoop, where Reverend Hall appeared moments later.

“Isn’t this a lovely evening?” he said.

Hall bade Louise good night. She watched as he walked down the street, disappearing into the dusk. She would not see him alive again.

The next morning, Friday, Louise awoke to the sound of shutters being drawn on the first floor, a telltale sign that Reverend Hall had gotten up early to catch a train to New York. Louise hopped out of bed and hurried downstairs to prepare breakfast. When she walked into the dining room a little after seven, however, she was greeted not by the reverend, but by his brother-in-law Willie Stevens, usually the last one to the table for breakfast. Seeing him at that hour was rather odd, but then again, Willie was nothing if not a little odd.

“What are you doing up so early?” Louise asked.

“I would rather have Mrs. Hall tell you,” Willie cryptically replied, suggesting something amiss.

As Louise passed the coatrack in the hallway, she put two and two together: the reverend’s hat was not hanging in its usual spot. He hadn’t come home.

Louise didn’t think much of it. The reverend always seemed to have a good excuse on those nights when he returned home late. His car had broken down. He’d missed the train back from New York. Someone needed a ride somewhere. On the other hand, Louise had never known him to stay out all night. She figured that after his appointment the previous evening, he must have been summoned back out on a sick call. Edward Hall would have stayed at the bedside of an ill friend or parishioner no matter the hour, or so Louise told herself. She set the table for three and acted none the wiser when Frances came down for breakfast about twenty minutes later.

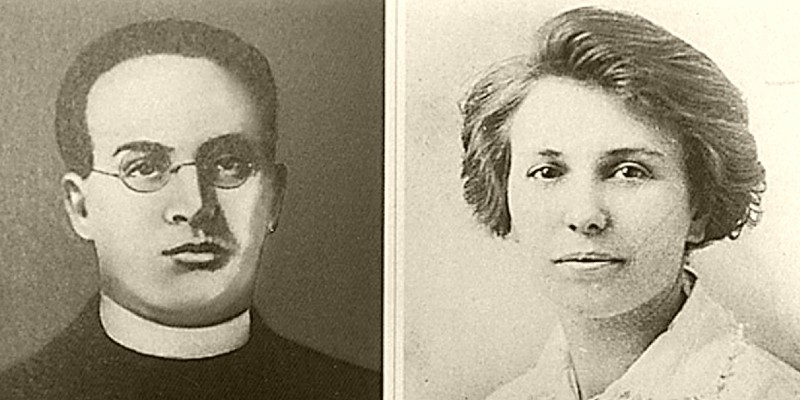

Frances was neither beautiful nor glamorous, despite her considerable wealth and aristocratic blood. She had a stocky build, which went well with her old-fashioned wardrobe. A reporter uncharitably described her as having “a face to look twice at—a long, narrow face” with a “firm, tight-lipped mouth, a suggestion of hair on the upper lip, a broad chin.” A crescent-shaped scar accentuated her right temple, and she had “unusually prominent” black eyebrows. Another journalist dispensed with the euphemisms altogether, stating that Frances had “the head and features of a man.” Her pince-nez glasses suggested, quite accurately, a woman of a different era. A new century ripe with opportunity had dawned and women’s roles in society were changing, but Frances wanted nothing to do with any of that. She wore her conservatism with pride.

While Frances never had children of her own, she was devoted to her family and its legacy, as well as to charity and her church, St. John the Evangelist, where she had taught Sunday school before meeting Edward, seven years her junior, when he ascended the pulpit there in 1909. She was everything you’d expect of a well-bred woman from the late-Victorian age: proper, imperious, and, of course, private. To a servant like Louise, Frances had a haughty air about her, but something seemed different when Louise greeted her employer that Friday morning in the dining room.

Frances sat down and picked at her food, hardly eating. Louise hadn’t set out the small silver water pitcher used by Reverend Hall to mix up his instant coffee substitute. Normally, Frances would have reminded Louise to retrieve it, but not today. There was an unspoken tension, and Louise finally piped up to break the awkward silence.

“Is Mr. Hall going to have breakfast in bed?” she asked, playing dumb.

“Louise,” Frances replied, “Mr. Hall has not been home all night. I do not know where he is.”

“Maybe he had an accident. Have you called the police?”

“I did. There hasn’t been any accident.” Frances had phoned the station around 7:00 a.m., but to avoid any unpleasant notoriety, she didn’t specify that Edward was missing.

Louise couldn’t help but notice an incessant jingling as she cleared the table. Frances held a set of car keys and rustled them nervously. That went on for most of the day as she paced the floor, rushing over to the window whenever she heard a car slow down outside the house. This antsy behavior did not suit Frances Hall, ordinarily a picture of calm and composure. As Louise would later say, “She had never acted this way before.”

That night, Louise eavesdropped on an intriguing phone call around 11:00 p.m. Her ears perked up when she heard Frances say, “No, there was nobody else. He was friendly with her. She’s in the choir.”

***

Frances Noel Stevens Hall came from New Jersey royalty on both sides: the Stevenses and the Carpenders. She took immense pride in her noble ancestry, which stretched back to the founding of the republic. Frances’s great-grandfather Ebenezer Stevens was the stuff of grade-school history books. He hurled tea into Boston Harbor and joined the Continental Army after the Battle of Lexington, later corresponding with founding fathers such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Another of Ebenezer’s many great-grandchildren, descended from his first and second wives, was a prominent New York woman who became a famous author. Her name was Edith Wharton.

Frances’s grandfather on her maternal side, Jacob Stout Carpender, was an early member of the New York Stock Exchange, whose wife descended from a man who gave the third public reading of the Declaration of Independence. Frances’s uncle Charles J. Carpender accumulated his wealth from a wallpaper company that later leased its headquarters to the founders of Johnson & Johnson. One of her cousins married Louise Johnson, the daughter of James Wood Johnson.

In New Brunswick, Frances’s family was akin to the Boston Brahmins. Their tony neighborhood, also home to the newly established women’s college of Rutgers University, was a menagerie of Carpender domiciles, including a twenty-one-acre retreat with a Tudor-style manor surrounded by immaculate landscaping and walking trails, a slice of English countryside in the middle of New Jersey. Frances’s residence, a three-story Victorian filled with dark wood paneling and heavy mahogany furniture, occupied a leafy plot that took up a full city block. She practically couldn’t throw a stone without hitting an aunt, uncle, or cousin. Her closest cousin, Edwin Carpender, lived around the block with his wife, Elovine.

It was Edwin whom Frances phoned on the morning of Saturday, September 16, some thirty-six hours after Edward had gone missing. “I knew something terrible had happened,” she later told a prosecutor, “and he seemed the only one I could get hold of.” When Edwin arrived at her house, Frances explained everything that had transpired: Edward leaving the house Thursday night, his absence through the following day, her sinking fear that he must be dead, or else why wouldn’t he have come home or called by now? “I am almost crazy,” Frances said.

Edwin, who had been out of town the previous day, was taken aback. This was the first he’d heard of Edward’s disappearance, and he could see the situation had rattled his ordinarily steely cousin. It did all sound strange and foreboding, but the best thing to do was to remain calm. No use jumping to conclusions. Surely there had to be a logical explanation.

In the meantime, Edwin and Elovine, one of Frances’s closest friends, tried to distract her. Elovine was sitting with Frances in the early afternoon when the phone rang. It was a reporter named Albert Cardinal from New Brunswick’s Daily Home News. A short while earlier, Cardinal had heard about the discovery of two bodies on an abandoned farm several miles from the Hall mansion. The property, known as the Phillips farm, abutted a lonely dirt road popular with trysting couples. The bullet-ridden bodies were found beneath a crabapple tree, maggots marching on their faces. They were posed with a stack of love letters between them, Hall’s calling card placed near his left foot. After venturing to the crime scene, inspecting the bodies, and picking up the card with Hall’s name printed in bold gothic letters, Cardinal had returned to his office and was now trying to establish, discreetly, whether Frances was yet aware of her husband’s death.

“Is this Mrs. Hall speaking?”

“Yes.”

“Is Mr. Hall home?”

“No.”

“When will he be home?”

“Why do you ask me these questions? Has anything happened to him?”

“I would rather let somebody else tell you.”

Frances hung up and immediately dialed the family attorney. She told him to get down to the newspaper offices right away and figure out what on earth was going on.

***

The Reverend Edward Wheeler Hall had a youthful glow offset by thinning hair, and brown eyes that beamed at his congregation under arched brows. While he was entirely average in height and build, and neither exceedingly handsome nor particularly hard on the eyes, Hall’s personality was intoxicating. He exuded a gregarious charisma that instantly warmed his parishioners. “If we could only count the consequences of our acts,” he preached during his inaugural sermon at St. John’s, “there would be very little sin.”

Hall’s penchant for oratory was apparent from a young age. At Polytechnic Preparatory School in Brooklyn, he’d served as vice president of the Literary and Debating Society, and president of the Interscholastic Debating League. At Hobart College in Geneva, New York, he was rumored to have been a “rather wild youth,” though a studious one, graduating cum laude in 1902.

Hall attended the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church and was ordained in one of the largest classes in the history of the Episcopal Diocese of New York. In the summer of 1909, Hall was serving as curate at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, when a position opened at St. John the Evangelist in New. Brunswick. The new role meant Hall would have his own congregation, one that included a number of prominent families. His fifteen-hundred-dollar salary afforded him a modest apartment near the church, where his widowed mother and sisters joined him.

For the first annual Christmas fair of Hall’s rectorship, he hired the Midget Athletic Club, which dazzled the audience with acrobatics and clown acts. He brought in students from Rutgers to compete in fencing bouts, and he corralled the men of the church for a talent show. Among the women of St. John’s who staffed an array of booths was a thirty-five-year-old bachelorette named Frances Stevens.

Frances was an outlier in an era when marriage had immense bearing on an upper-class woman’s identity, and a bride’s average age was twenty-one. She spent most of her time with her mother, reading, dining, and playing cards. Until Edward came along, it seemed all but certain that she would end up a spinster.

What did Edward, twenty-seven, see in Frances, stuffy and old fashioned, hardly the belle of the ball? It’s not inconceivable that her wealth had something to do with it. (In 1922, the newspapers reported that she was worth $1.7 million, the equivalent of nearly $30 million today, though she later disputed this.) As for Frances, becoming the wife of an esteemed local cleric may have been a way to further enhance her social position. (It also may have been preferable to becoming an old maid.)

On the afternoon of July 20, 1911, New Brunswick’s upper crust filled the pews of Christ Church, transformed into a wilderness of palms, ferns, and gladiolas. As the organist commenced the nuptial music, the guests turned their heads toward the entrance, where Frances appeared in a princess gown of rich white silk and Mechlin lace. It was the same one worn forty-three years earlier by Frances’s mother, who gave the bride away.

Clutching a bouquet of roses and lilies of the valley, her tulle veil done up in coronet fashion with orange blossoms, Frances proceeded down the aisle and took her spot at the altar, locking eyes with her groom-to-be. After exchanging vows, the newlyweds hosted a reception at 23 Nichol Avenue, where guests showered them with silver, furniture, china, paintings, and checks. It may have been a curious match, it may have been a marriage of convenience, but whatever the truth of their relationship, Edward and Frances had promised themselves to one another, in sickness and in health, ’til death do them part.

For Edward, he had another eleven years, one month, and twenty-five days to go.

***

Back at the Phillips farm, as the maggots worked their way up Edward’s nostrils and under his eyelids, Detective George Totten surveyed the crime scene through circular eyeglasses that looked too small for his face. He’d arrived at the crabapple tree with several other county officials more than an hour after the bodies were found. His homburg hat kept the sun out of his eyes as he noticed clues that may or may not have had any significance. A county physician made his own inspection, determining that unless Hall had been sleeping at the very moment he was shot, someone had to have closed his eyes and repositioned his glasses postmortem. (The physician also noted that Hall’s fly was zipped up.) The county sheriff began packaging up evidence: the love letters, two handkerchiefs, a set of keys, a .32-caliber cartridge, Hall’s calling card. Totten wasn’t sure if the victims had died where their bodies were found, or if they’d been taken to the spot after perishing elsewhere. But in the absence of a gun, Totten knew this was no suicide pact.

“Everything points to murder,” he said.

By early afternoon, the Phillips farm had come to look more like a country jamboree than a homicide investigation. In a chaotic scene that would have horrified any student of the burgeoning forensic sciences, curiosity seekers arrived in droves, to the point where the patrolmen either couldn’t hold them back or didn’t bother trying. They parked their cars along adjacent roadways and trudged through fields to the awaiting circus. The mob freely roamed and gawked, some stomping about the corpses, picking up the reverend’s hat and the woman’s scarf. Pieces of bark were stripped from the crabapple tree, morbid souvenirs. An onlooker later remarked, “You could not believe it possible, in a place as isolated as that, that people could come in such numbers in ten minutes.”

Totten was inside the farmhouse when a second reporter from the Daily Home News, Frank Deiner, showed up and said, “I think I can identify the woman.”

Denier, who lived around the block from the Hall home, knew something the others did not. There were rumors Hall had been “friendly,” as Deiner put it, with a woman named Eleanor Mills, a choir singer at Hall’s church. Totten immediately escorted Deiner through the crowds to the blood-soaked patch of earth where the bodies lay. Deiner leaned in, drew down the woman’s scarf, and squinted past the maggots. There was no doubt in his mind—this was Eleanor Mills, wife, mother, and devoted congregant of St. John the Evangelist.

Before long, Frances’s family attorney arrived on the scene with Edwin Carpender. They’d received word about the murders, and they needed to see the truth with their own eyes. Standing over the bodies, they could hardly believe it was real. Before the county undertaker pulled up to retrieve the bodies, Carpender leaned down and took Hall’s cold dead hand in his own.

Shortly after one o’clock, Elovine Carpender returned with trepidation to 23 Nichol Avenue. She had learned of Edward’s death and now had to inform Frances of the grim news. She climbed the stairs to the second floor, where Frances awaited her.

“What you feared has happened,” Elovine said. “He is dead.”

Hearing these words, Frances abandoned her reserve. As Elovine put it, “She broke down completely.” Elovine hugged her friend as the emotions poured out. Frances regained her composure, and after she caught her breath and dried her eyes, she went downstairs to the parlor, where visitors were arriving to pay their respects.

Her ordeal had only just begun.

___________________________________

Excerpted from the book BLOOD & INK: The Scandalous Jazz Age Double Murder That Hooked America on True Crime by Joe Pompeo. Copyright © 2022 by Joe Pompeo. From William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.