It’s the waiting. That’s what’s getting to me, way more than I thought it would. It’s like the time I went for blood tests, after this trip to Kavos I went on with my mates and ended up on the beach with this girl. Which happened way before I ever met Syd, by the way, and which is something I never, ever did again.

And conveyancing. Waiting for the house to go through. That was incredibly stressful, too, even though there was basically nothing for us to do. Because of that, probably.

It wasn’t like this, though. Neither one of those things was like this. This is worse—much worse—mainly I guess because I still don’t know what exactly I’m waiting for.

Syd’s right. The house: it was a bargain. OK, so it wasn’t exactly my dream home or anything (for the record that’s a cottage on the north coast of Devon, overlooking the sea, near some woods and an hour minimum from the closest Starbucks), but the price we got it for in my mind made up for a lot. We didn’t need three bedrooms, but it’s like most things, I suppose. No one needs an iPhone. Or a convertible. Or a Dualit toaster. But some things, they’re nice to have even if you’d struggle to justify them if you were hauled up before, let’s say, Jeremy Corbyn.

Three bedrooms. I could have a study. Or a den? Half a one anyway, and Syd could set up her yoga mat on the other side. As for the spare room . . . neither one of us had any family that was likely to come and stay (apart from my parents, maybe, at some point—if they could bring themselves to set aside for a night their feelings about Syd) but it would be useful for putting up friends and, who knew, maybe one day, if Syd ever came round to the idea . . . Well. It was nice to have options, that’s all I’m saying, particularly after living the way we had. I’d met Syd at a conference her firm was running on mental health care. I’d been sent there by Lambeth Council as a delegate and she noticed my job title and commented on my age (this was four years ago, so at the time I would’ve been twenty-four, the same age as Syd), on how demanding being a social worker must be, and I’d acted like no, really, it’s not such a big deal, while also trying to convey that actually, yeah, it was, but managing events, that must be pretty tough too, and . . .

I’ll spare you the details.

The point is, since we’d known each other we’d lived a minimum of eleven Tube stops apart. We’d discussed moving in together before, but we knew that if we did it would take us longer to save up for our own place, so instead we decided to tough it out. For a year, we thought, tops. It turned out to be the better part of three. So getting the house, getting the keys . . . it was all exactly the way Syd said it was. The anticipation. The relief. That bloody barn owl. Maybe I never loved the house the way Syd did, but I definitely loved the fact that it was ours.

house seemed less creepy than it had before and more characterful. Less gloomy, more atmospheric.So anyway, we’re in. Still not entirely understanding how we’d swung it, but once the contracts had been exchanged what did we care? And, for a short while at least, I changed my mind. The house seemed less creepy than it had before and more characterful. Less gloomy, more atmospheric. It was odd, though. The stuff, I mean; all the junk the former owner had left behind. Because before the smell, before what it led to, it already felt to me like . . . I don’t know. Or actually I do know, I’m just wondering how much of what I’m putting down is accurate. Whether things have got twisted. Tinted, in the light of all the stuff that’s happened since.

But yes, I think I felt it even then. This new life of ours that Syd and I were both so pleased about—I definitely had a sense that it was something we’d stolen.

The smell.

We’d run out of money so we couldn’t pay for house clearance and anyway we thought it would be fun. You know, going through all the previous owner’s old stuff. It was Syd’s suggestion really. Me, I would have dumped the whole lot in bin bags and taken it all either to charity shops or the tip, but Syd convinced me by talking about all the things we might find. There might be furniture we could use, or books we wanted to read, or inspiration in a stack of correspondence for my elusive, long-gestating novel. Treasure of one kind or another, anyway.

(I know, I know: ironic, right? Considering what we did find, I mean.)

We’d got rid of those birds. Or I had, before Syd would even contemplate moving in. (It won’t take a minute, I’d told her. All I need to do is open a window. But Syd had been too resolute on the matter even to groan.) We’d cleared the kitchen too, and the master bedroom. The rest, though—we were in no hurry. It’s not like we were struggling for space. Between us the only furniture we owned was my old sofa, plus the mattress we’d had delivered the morning we picked up the keys. So day five maybe, day six, we were sitting on the carpet in the second bedroom going through a mountain of old vinyl we’d discovered. There was a record player in there too (an actual record player, completely unironic), and as we came across LPs we liked the look of we were sticking them on the turntable. The previous owner, he’d built this seriously formidable collection of movie soundtracks. Nothing more recent than The Godfather, and nothing with lyrics, but as well as the obvious composers (Maurice Jarre, Ennio Morricone, Bernard Herrmann), there were some real, hard-to-come-by classics. An original Max Steiner, for example. Another by Miklos Rozsa. As I said: treasure.

Syd, she was pulling out all the show tunes. My Fair Lady, Oklahoma!, Grease. The Sound of bloody Music. We were taking turns to educate each other. Neither one of us prepared to learn a thing, but each of us having a grand old time nonetheless.

Until Syd started sniffing at one of the record sleeves.

‘Syd?’

She was looking at the soundtrack of To Kill a Mockingbird as though it was something distasteful.

‘Do you smell that?’ She sniffed the cover again, then the air.

I did. I’d smelled it for a while. It was just damp or something. A mouldy pair of trainers we’d yet to discover at the bottom of one of the wardrobes.

‘It’s not the record sleeve, Syd. Gregory Peck’s far too much of a gentleman to make that kind of smell in front of a lady.’

Syd smiled and rolled her eyes, bumping my shoulder with the record sleeve.

‘It’s like . . .’ She sniffed again. ‘What is it? Is it coming from in here?’ She uncrossed her ankles and got to her feet. Syd never wears skirts, only trouser suits or jeans. She doesn’t like showing her skin, particularly on her arms. The way she feels obliged to dress makes her feel self-conscious—‘mannish’ in her words—but the truth is she’s got no reason to worry. Whatever she’s wearing, whatever the situation, she moves with the grace of Audrey Hepburn.

I joined her in chasing the smell around the bedroom, only slightly annoyed because it was my record we were being distracted from on the turntable.

I’d smelled it for a while. It was just damp or something. A mouldy pair of trainers we’d yet to discover at the bottom of one of the wardrobes.We ended up on the landing, inhaling and exhaling like a pair of overexcited police dogs. All I can think, looking back, is that the smell had worsened that day because of the weather. It had been cool and wet for most of the month—for most of the year—and finally, on that bright day in May, we were getting a taste for the first time of the impending summer.

‘It’s definitely stronger out here,’ Syd declared, a shard of light from the landing window cutting right across her furrowed forehead.

The smell did seem to be at its worst where we were standing. The trouble was, there didn’t appear to be anywhere it could have been coming from. There was no space on the narrow landing for anything but the pictures on the walls (black-and-white family photographs mainly, interspersed with the occasional, obligatory, bird). The nearest door was the one to our pop-up music room, the door through which we’d just come.

‘Is it the drains maybe?’ Syd asked me. ‘The soil pipe or something?’

I was only seventy-five per cent certain at that point what a soil pipe actually was, but if I was right it didn’t seem that type of smell. It was more like . . . rotting fruit. Or the bins at the back of a restaurant.

I looked up.

Syd joined me.

‘The attic?’

I shrugged. The hatch was directly above our heads. We hadn’t been up there yet. It would be crammed with junk, we’d supposed, and there were other parts of the house we wanted to clear first. Plus, personally? I’m not overly friendly with spiders.

‘Shall I get the stepladder?’ I asked. It wasn’t really a question. More a delaying tactic.

‘I’ll go up,’ Syd said, sensing my fear. She makes clucking sounds whenever she sees a spider, then carries them to the nearest window in her hand.

‘No,’ I countered. ‘Don’t be silly.’ My father again, channelling through me when he wasn’t even dead. Because drainage issues? Involving ladders? That was man’s work.

I was glad I said it, though. I was glad in the end that I did go up that stepladder first. Because once I figured out how to turn on the torch and I realized what it was that was up there . . . Well. I had a chance to warn Syd, if nothing else.

‘Don’t come up here,’ I called out. ‘Syd? I mean it. Don’t come up.’

__________________________________

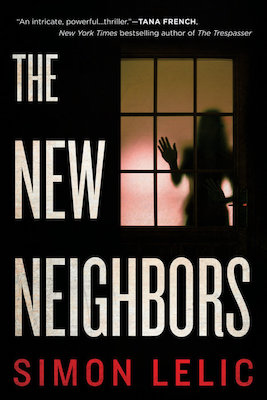

Reprinted with permission from The New Neighbors by Simon Lelic from Berkley Publishing Group, copyright 2018.