Love kills.

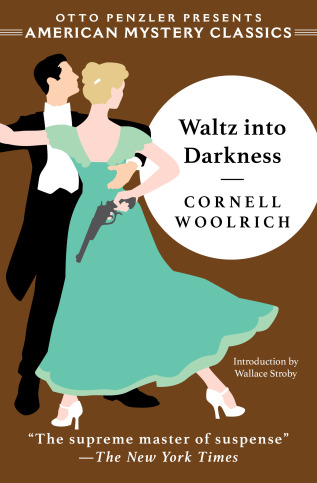

Nowhere is that truer than in the work of Cornell Woolrich, America’s greatest noir novelist. And in that work, there is no better example than Waltz into Darkness.

First published in 1947, Waltz was written under Woolrich’s William Irish pseudonym, which he had previously used for his novels Phantom Lady and Deadline at Dawn. It came near the end of an incredibly prolific period in his creative life—from 1940 to 1950—that saw the publication of eleven classic suspense novels and dozens of short stories.

Woolrich’s longest novel, Waltz trades his usual Manhattan nightscapes for the gaslight and cobblestones of 1880 New Orleans. All that poor Louis Durand, the novel’s ostensible hero, wants is to love, and be loved. Fifteen years earlier, his fiancée died of yellow fever on the night before their wedding. Now an affluent businessman at thirty-seven, Louis is nonetheless lonely, lost, and terrified of growing old alone. He contracts for a mail-order bride from St. Louis, in what he calls “the bargain he had made with love, taking what he could get, in sudden desperate haste, for fear of getting nothing at all.”

But when Julia Russell, his bride-to-be, arrives, she looks nothing like the pictures she’s sent, and her stories don’t match what she’s recounted in her letters. Blinded by love and need, Louis accepts her explanations without question, and ignores those first ominous clues that she’s not what—or who—she claims to be.

Petite, blond and lovely, Julia (or Bonny, as her real name may or may not be) is nevertheless the most fatale of femmes. Louis is soon ensnared—helplessly and willingly—in her web. When Julia empties out their joint bank account and flees the city, Louis pursues her across the American South with murder in his heart, only to fall back in love with her after they’re reunited in a typically wild Woolrichian coincidence. Driven to desperate ends, Louis finally commits an act in her defense from which there is no return. His fate is sealed.

Waltz feels written from a well of pure emotion. His trademark doomed romanticism haunts every page.Despite its uncharacteristic setting and ambitious scope, Waltz is vintage Woolrich. Julia/Bonny is another in his series of fascinating female characters—angels bright and dark. Woolrich women could be driven by revenge (The Bride Wore Black), unrequited love (Phantom Lady) or a quest for justice (The Black Angel). Julia/Bonny’s primary motivation is greed, but she’s a self-made woman as well. She drinks, smokes, and cheats at cards, with no apologies. Louis loves her anyway.

The novel also revisits one of Woolrich’s favorite themes and subtexts—the elusiveness of identity. Do we really know this person next to us? Do we really know ourselves? What are we capable of when driven to extremes? His stories are filled with characters being pursued for crimes they didn’t commit. Or maybe they did.

On the classic question of free will versus predestination, Louis—and by extension Woolrich—is firmly in the second camp. “It’s already too late,” Louis admits at one point. “It’s been too late since I first met her. It’s been too late since the day I was born.”

Woolrich’s own ill-fated life has become the stuff of legend. The son of a wealthy globe-trotting engineer and a New York socialite, he settled in Manhattan and attended Columbia University (then Columbia College) in the early 1920s. While living with his mother’s family in a Harlem brownstone, he began to devote himself to writing. His first novels were Jazz Age society tales patterned on the work of F. Scott Fitzgerald, but he later began submitting mystery stories to the penny-a-word pulp magazines of the day. Following a brief, failed marriage in 1930, he lived with his mother in a series of New York residential hotels until her death in 1957.

An alcoholic and by some accounts (but not all) a closeted homosexual, Woolrich lived a solitary life, even as his novels and short stories were permeating popular culture. His sturdy suspense-filled plots and visual writing made his work a natural for adaptation to radio, film, and eventually TV. From 1940 to 1954 alone, there were eighteen films based on Woolrich properties. These included high-profile Hollywood fare such as Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 Rear Window (based on Woolrich’s 1942 novelette “It Had to Be Murder”) and B-movie sleepers such as 1949’s The Window (from the short story “The Boy Cried Murder”) and Val Lewton’s The Leopard Man (based on the novel Black Alibi). To date, more than a hundred films and TV shows have been made from his work in a half-dozen languages.

Woolrich himself was no fan of the films based on his books, at least the ones he saw. In a 1947 letter to Columbia professor Mark Van Doren, he claimed to be “ashamed” by Roy William Neill’s film version of The Black Angel. “It took me two or three days to get over it,” he wrote. “All I could keep thinking of in the dark was ‘Is that what I wasted my whole life at?’ ” Years after the New York premiere of Rear Window, he was still angry at Hitchcock for not inviting him. It’s uncertain if he ever saw the film.

Waltz has been filmed twice, first in 1968 as Mississippi Mermaid, directed by François Truffaut, who a year earlier had adapted The Bride Wore Black. Mermaid starred French matinee idol Jean-Paul Belmondo as Louis, and a luminous Catherine Deneuve as Julia, resetting the story on a French island in the Indian Ocean. In 2001, the book was filmed again as Original Sin, starring Antonio Banderas and Angelina Jolie, this time relocated to nineteenth-century Cuba.

This is noir so strong it warps reality. The stories unfold with the logic—and inevitability—of a nightmare. His protagonists are haunted and hunted, tripped by fate and trapped by the night.Like many of Woolrich’s novels, Waltz feels written from a well of pure emotion. His trademark doomed romanticism haunts every page. Though his style is often idiosyncratic—with a fondness for comma splices, adverbs, and descriptions that run a sentence too long—it’s hard not to be swept away by the lushness of his prose. At times, he’s also capable of an almost-poetic terseness. As Louis’s dream marriage unravels, Woolrich gives it a simple eulogy. “The house was dead. Love was dead. The story was through.”

It would be a spoiler to mention too many of the reversals in store, except to say that Woolrich’s mastery of suspense is in peak form here. As he does in his best work, he invests the novel with a pervasive undercurrent of dread. The fact that his plots don’t always make much sense, or rely too heavily on coincidence, only makes them more effective. This is noir so strong it warps reality. The stories unfold with the logic—and inevitability—of a nightmare. His protagonists are haunted and hunted, tripped by fate and trapped by the night.

Woolrich’s own already-unhappy life began to spiral after his mother’s death. Infirm and alone, he slipped into self-imposed obscurity even as his work continued to generate substantial income. The writer Barry N. Malzberg, who was Woolrich’s agent during the last year of his life, remembers him as “a crushed, lonely, and timorous soul, always seeking friendship, finding—because of his naked need—little.”

A diabetic, Woolrich eventually lost a leg to gangrene after failing to seek medical attention for an infection. He spent his final months as a recluse, confined to a wheelchair in his one-bedroom apartment at New York City’s Sheraton Russell Hotel. It was there he died from a massive stroke on Sept. 25, 1968 at the age of sixty-five. Only a handful of people attended his funeral.

Woolrich’s last major attempt at a novel, the posthumously titled Into the Night, was unfinished at the time of his death (it was later completed by Edgar Award-winning novelist Lawrence Block, and published in 1987 by The Mysterious Press). Woolrich also left behind chapters of a beautifully written—though likely highly fictionalized—autobiography, Blues of a Lifetime. In the chapter “Remington Portable NC69411” (the make of one of his early typewriters), a deeply depressed Woolrich looks back nostalgically—and painfully—on his days as a young writer. He remembers long happy nights on the second floor of the Manhattan brownstone he shared with his mother, grandfather and aunts, crafting his first novel, 1926’s Cover Charge, in a white-hot rush, writing by hand, reveling in the fierce joy of his art and talent:

“I was so hooked on it that I couldn’t have given it up for love nor money. So every evening after my meal was over I’d sit there, anywhere from nine to eleven-thirty or twelve . . . a single lamp lit behind me on a pedestal in the corner . . . Every now and again I’d take a breather, lean back to rest my back and ease my neck, and put out even the one light, to facilitate the gathering of new thoughts for the pencil bout to come.

“I never forgot those chiaroscuro seances in that second-floor room. . . . I like that kid, as I look back at him; it’s almost impossible not to like all young things anyway, pups and colts and cubs of all breeds. But I feel dreadfully sorry for him, and above all, I wish and pray, how I wish and how I pray, that he had not been I. He might have had a better destiny, if he hadn’t been, he might at least have had a chance to find his happiness.”

A sad and haunted life, but what beautiful work he left us. Stories of love and obsession, fate and fear, the things that never change. And—most Woolrichian of all—the doom that hovers over us always, waiting for its moment to arrive.

____________________

Excerpted from Waltz into Darkness by Cornell Woolrich, available now from Penzler Publishers.