It was getting dark when I left the Boston hospital after working the day shift. My sister was coming to town to see my new apartment, and I still had to hang the last pair of curtains. If I hurried, I could get to the Mission Hill hardware store to buy the rods and brackets I needed before it closed.

I felt my bag being yanked from my shoulder before I saw that the person attacking me from behind was practically a child. As soon as I realized what was happening—that I was being robbed—I let go of my purse. The kid, who couldn’t have been more than twelve or thirteen, and looked as scared as I felt, had full possession of my bag when he kicked me squarely in the knee. Perhaps it was the pain sending electrical shock waves through my body, or maybe it was my incredulity that he’d successfully stolen my wallet and keys and still felt the need to hurt me, but I kicked him back. Hard. Where it counts, as they say.

Doubled-over, he dropped my bag. I grabbed it and ran as fast as a person with a knee injury can, back to the hospital.

The second time someone edged up behind me with sinister motives was two years later. Again, it was a fall afternoon when it gets dark early in New England. I was on a side street just outside Copley Square, deemed a safer part of the city in which to walk alone when I felt something sharp between my shoulder blades. I’ll never forget his hot whisper in my ear. “I have a knife. Let go of your bag.”

I never saw the perpetrator’s face. I didn’t fight back. In fact I barely moved even after I was certain I was alone on the sidewalk. Finally, booking it toward Boylston Street, I hailed a cab. I didn’t tell the driver I had no way to pay for the ride home until he pulled up in front of my apartment. His lack of compassion is a story for another day.

These two muggings remain with me decades later, not because they are the scariest experiences I’ve ever had, or even considered heinous by any measure. But because my automatic brain refuses to let them go.

Unexpected events or surprising encounters have the power to ignite the stress response, also known as the fight-flight-freeze mechanism. To this day, if anyone approaches me from behind or enters a room too quietly startling me, I can be flooded with emotion, overwhelming my sense of safety. Even when I’m not truly in danger.

So why would someone like me want to write about trauma? Why would anyone read it?

That’s a bit like asking a therapist why people should talk about difficult life experiences. (Full disclosure: In addition to being a fiction writer, I’m also a family counselor.)

In both cases, it’s because the stories we tell and the ones we read help us process conflicting emotions and contend with complex relationships. Numerous studies confirm what every fiction writer knows—that story is an incomparable vehicle for the exploration of human social and emotional life. Literary critics and philosophers have long advanced the notion that one of fiction’s main jobs is to raise consciousness.

Jonathan Gottschall wrote in his book, The Storytelling Animal that, “Human minds yield helplessly to the suction of story. No matter how hard we concentrate, no matter how deep we dig in our heels we can’t resist the gravity of alternate worlds.”

The act of reading fully engages the brain impacting memory, learning, and problem-solving. Steven Pinker author of How the Mind Works suggests, “that stories equip us with a mental file of dilemmas we might one day face, along with workable solutions.”

I gravitate toward crime fiction and domestic suspense novels because they’re embedded with instructions on how to navigate a life. I write about grief and trauma to gain insight into the psychology of people faced with what I fear most. Perhaps also in hopes I can learn how to protect my family and myself.

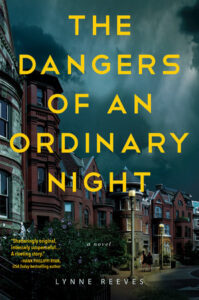

Of all of my novels, my latest, The Dangers of an Ordinary Night offers the greatest opportunity to engage readers in conversations about the experience of hyper-vigilance women experience in the aftermath of trauma. What happens when trust in our most precious relationships is lost? How, in an instant, can our lives change in unrecognizable ways all because of the actions of others? And why do feelings of guilt and regret impact our lives long after we’ve experienced traumatic events?

Worked into the story both implicitly and explicitly are the lessons my characters learn about loving again after being deceived. And learning to trust despite the desire to be protective emotionally.

It’s my hope that this story about the ripple effects of addiction on partners and children will create opportunities for thoughtful conversations around mental health issues that are often difficult to talk about.

Perhaps, like me, you’ve endured experiences that cast a long shadow. If so, I hope you’ll find my novel transformative, as a means to revisit themes in a positive, therapeutic way, in an effort to keep learning from them.

***