At 1:30 p.m. on Friday, November 29, 1983, a man the FBI called the Yankee Bandit walked into the lobby of a Bank of America in the Melrose district of Los Angeles and stood in line. When he got to the teller window, the well-dressed man politely informed the woman on the other side of the counter that he had a gun and would she please hand over the cash. After tucking $1,740 into a briefcase, he apologized for any trouble, thanked her, and left.

Thirty minutes later, The Yankee was sixteen blocks west at the City National Bank in the Fairfax district going through the exact same routine and walking out with $2,349. Still moving west, he hit a Security Pacific Bank in Century City 45 minutes later, but bailed out with no money when the teller starts freaking out on him. Undaunted, he walked one block over and cordially robbed the First Interstate Bank there for $2,505.

Less than an hour later, he walked out of Imperial Bank in Westwood, practically in the shadow of the Federal Building that houses the FBI’s L.A. Bank Robbery Squad, with $4,190. Diving into rush hour traffic on the 405 Freeway, The Yankee headed over the hills to the San Fernando Valley and pulled a final job just before closing time at the First Interstate in Encino for a take of $2,413. Four hours, six heists, $13,197.

As impressive as The Yankee’s performance had been, a record for bank licks by one person in a single day, It did not entirely shock the FBI agents in bank robbery squad. This was L.A. after all, and by 1983, L.A. had long established itself as the undisputed “Bank Robbery Capital of the World.”

At the time of the Yankee’s record spree, Los Angeles was on the brink of the greatest bank robbery epidemic ever seen. Between 1985 and 1995 the approximately 3,500 retail bank branches in the region were hit 17,106 times. 1992, the worst year of all, there was an almost unimaginable 2,641 heists, one every 45 minutes of each banking day. On a particularly bad day for the FBI that year, bandits committed 28 bank licks. There were years during that stretch when the L.A. field office of the FBI, which covers the seven counties in the Los Angeles metro region, handled more cases than the next four regions combined.

***

“Of all the bank robberies in the nation over the past three or four decades, at least 25 percent of them have gone down within commuting distance of the soaring white spire of City Hall,” writes former FBI Special Agent William Rehder in his 2003 book Where the Money Is: True Tales from the Bank Robbery Capital of the World. Rehder should know; he was the Feds’ lead man in charge of solving L.A. area bank robberies throughout the 1980s and 90s.

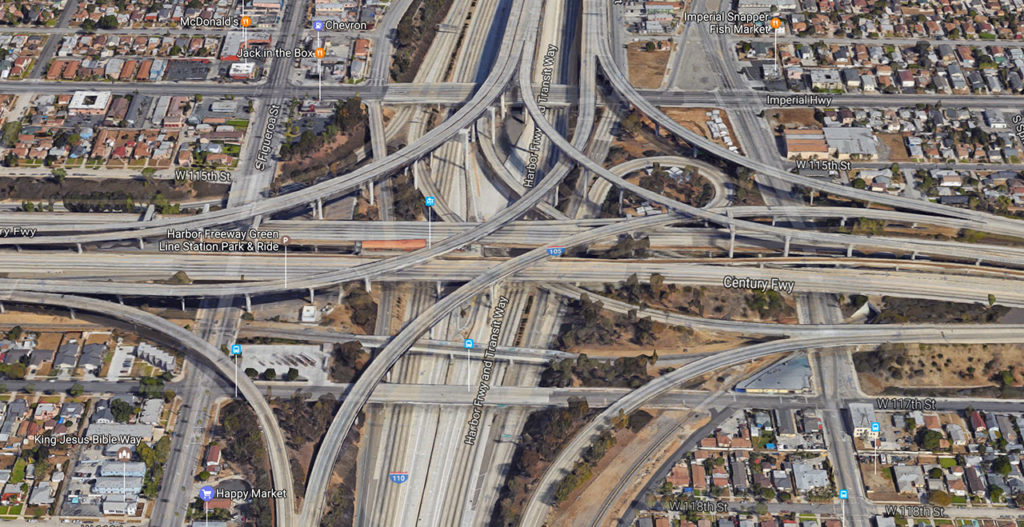

So why L.A.? Sure, part of it is the sheer size of the area covered by Rehder’s L.A. bank robbery squad at the time: 10,000 square miles and close to 17 million people. But size alone does not explain its position at the top of the bank robbery heap. In no other category of crime does L.A. ever rank at the top. Just this one. But the one factor most responsible is a product of that sprawl and something that has come to define Southern California culture: Cars.

With more than six million vehicles and more than 1,000 miles of freeway upon which to roam, Los Angeles has created a landscape ideal for bank robberies. By hitting a bank near a freeway onramp, a holdup man can jump on and off and be anonymously cruising surface streets miles away in a completely different police jurisdiction before the cops even get to the crime scene. Switch to a cold car or swap your stolen plates for legal ones and… see ya.

It was not the first time the automobile has acted as a major game changer in the bank robbery world. It was the advent of the getaway car and an adequately networked road systems that enabled depression-era gangsters like Pretty Boy Floyd, John Dillinger, and Bonnie and Clyde to hit a bank and disappear over state lines. In an era when interstate communication among law enforcement was virtually nonexistent, they were as good as gone. The federal government’s attempt to solve the problem catapulted a young bureaucrat named J. Edgar Hoover into the public spotlight and created the modern version of the FBI.

The Southern California car culture contributed to the problem in more indirect ways. In a suburban sprawl, running routine errands often entailed hours behind the wheel driving from spot to spot, climbing in and out of the car over and over. Put a few hungry kids in the back seat and a parent was facing a daily exhausting ordeal. After watching the wildly successful rise of the fast food industry, it did not take the rest of the local business community to realize that in L.A., convenience was king. And for Southern Californians, nothing is more convenient than the bottom of a freeway off ramp. As it just so happens, nothing is more convenient for a bank robber than the on ramp just across the street.

If customers no longer wanted to drive twenty minutes to do their banking, it soon became obvious they also no longer wanted to do it in fortresses with thick granite walls, armed guards and bars over the teller windows. Soon, branch offices took the warm and fuzzy approach, transforming their lobbies to look more like the customer’s living room than Fort Knox. High-pile carpeting replaced marble floors and upholstered chairs were substituted in for the hard, wooden variety. All the outward trappings of security were dropped. No more guards, high teller counters, double doors, unsightly plexiglass bandit barriers or anything else that might distance a customer or cause her to associate banking with crime.

By 1980, retail banking had metastasized into thousands of storefront branches across the L.A. region, many of them situated along prime getaway routes with very little security with which to guard them.By 1980, retail banking had metastasized into thousands of storefront branches across the L.A. region, many of them situated along prime getaway routes with very little security with which to guard them. The bank robbing community slobbered over the new target-rich environment like a cartoon wolf. Word was out. Follow a few simple rules and you could make some fast cash with little chance of getting caught in the act. And then cocaine showed up on the scene and suddenly there were a whole bunch of people out there who needed some fast cash. That’s when things got crazy.

It was cars, freeways and convenience that propelled Los Angeles to the lead in bank robberies, but the meteoric rise in cocaine use beginning with the late 1970s disco scene sent the actual numbers through the roof. L.A.’s notorious party culture and laid back attitude toward recreational drug use made sure that the area was hit especially hard. When cocaine made its run to the top of the glamour drug chart beginning in the mid-1970s disco era, another staple of the L.A. cultural landscape came into play and kicked it into high gear: Celebrities. Rock stars, porn stars, movie stars, fashion trend-setters and the rest of the glitterati were so open, proud and flaunting of their coke use that celebrities effectively became walking advertisements for the drug. Los Angeles quickly developed a notoriously blow-centric club scene. In a city where seemingly everyone wanted to be a star, the trickle-down effect was almost instantaneous. Soon every dance floor in the region was awash in the stuff, whether it be on the Sunset Strip or Disco Night at the Black Angus Steakhouse in Riverside.

South American drug cartels quickly began flooding the market with the white powder and prices plummeted 80% in some places. For the first time ever, cocaine was in the price range of the common man, and when the common man became addicted to coke he ran out of money fast. And if he couldn’t kick his habit, he went out looking for more of both.

In the last half of the 1970s, the number of bank robberies nationwide shot up 71 percent topping 6,000 in 1980. During that same time, the profile of the typical bank robber shifted from seedy, career criminals to white, middle-class businessmen, blue collar construction workers and small-business owners, mostly first-time offenders who had recently lost their jobs, businesses and savings to their addiction. And then the early 1980s came and people started smoking the shit, first as freebase and then in the form of the viciously addictive crack. Enter the Yankee Bandit.

***

The most prolific one-on-one bandit of all time fit perfectly the profile of the cocaine-era bank robber. Eddie Dodson was a mild-mannered, likable owner of a wildly successful antiques store in fashionable West Hollywood frequented by celebrities such as Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, and John Lennon. Thick into the Hollywood hipster scene, Eddie began sniffing and then smoking coke. In July of 1983, Dodson, a man with no previous police record whatsoever, walked into the Crocker National Bank in Larchmont and pulled his first bank heist. After a few more, Dodson was given the honor of a nickname from the L.A. FBI Bank Robbery Squad, who labeled him the “Yankee Bandit” because of the baseball cap he often wore during the heists.

The Yankee was what Rehder called an “apology bandit,” always saying something to the effect of “I’m sorry to have to do this,” as the teller handed over the cash. Like all addiction-driven bandits, Dodson’s income from robbing banks funded a habit which only got worse and worse, requiring even more heists to feed. Rehder says he could often tell which of his serial bandits were the addicts because they looked more and more dope sick in each progressive bank surveillance photo. Rehder even got to where he could gauge the size of their habit by the accelerating frequency of the robberies required to feed it. That, along with other M.O. traits, often allowed him to anticipate the timing of their next job with surprising accuracy.

The Yankee had 55 jobs under his belt in his short career, surpassing a guy known as the “Brown Bag Bandit” to become the all-time world record holder.By January of 1984, The Yankee had 55 jobs under his belt in his short career, surpassing a guy known as the “Brown Bag Bandit” to become the all-time world record holder. In six months he had scored more than a quarter million dollars and pissed it all away on a coke and heroin “speedball” habit that was up to $15,000 a week. His long run wasn’t because he was any better than all the others; just luckier. But that luck ran out in late February 1984 after 64 bank licks when a line teller followed him out of a bank at Sunset and Vine and dogged him on foot until the cops showed up.

In the end, the Yankee Bandit was caught for same reason virtually all bank robbers eventually get caught. “Bank robbery is an addiction,” Rehder says. “Nobody robs just once.” And like the Yankee, everyone’s luck eventually runs out. The average life span of a bank robber with a coke habit was about six months. The end usually came in the form of someone jotting down a license plate, a police unit cruising nearby when the 2-11 “robbery in progress” dispatch goes out, a dye pack exploding on them, or, like the Yankee, some foolishly ambitious bank employee simply refuses to let the bandit just get away.

By the time the Yankee was finally captured, the crack epidemic was in full swing, on its way to devastating all strata of American society. In 1985 alone, the number of people who admitted using cocaine on a routine basis increased from 4.2 million to 5.8 million, most of it due directly to the rise in crack use. By 1985, local L.A. area bank robberies had shot past 1,000. By 1990, it had jumped another 56% to 1,644. Rehder estimates that during that time, up to 85% of all bank robbers were addicted to one drug or another, mostly crack cocaine, but also including methamphetamine or heroin.

Almost all of the drug-fueled bank robbers were of the one-on-one note passer variety—one bandit robbing one teller with a “I’ve got a gun, give me the money” type note. These rarely ended in violence. Not only was this breed of bank robber not violent by nature, but the banks’ instruction to their employees was simple: give them what they want and get them the fuck out as fast as possible before someone gets hurt. So despite the seriousness with which law enforcement was treating the soaring bank robbery rates, it never rose to the level of concern of other problems they had on their hands, such as gang violence and domestic abuse. But all that was to change in a single day.

***

On September 5, 1991, two heavily-armed men wearing wigs and fake mustaches strolled into the lobby of the Wells Fargo bank on Ventura Boulevard in Tarzana, California and announced they were robbing the joint. Unfailingly polite, the “West Hills Bandits” gathered employees and customers together and told them to stay calm and “enjoy the show.” They then proceeded to clean the place out of all its cash—the vault, teller line, the reserves… everything. Finishing up their work in less than two minutes, they exited the branch with a cheerful “Thanks everyone!” Outside, they hopped in a getaway car and melted away into the hundreds of thousands of vehicles using the Los Angeles freeway system at any one time.

When the FBI finally did catch up with Gilbert Michaels and James McGrath, they turned out to be a pair of religious whack-jobs, “Prophets of God,” battling the evil “Luciferians” among us—which apparently included Wells Fargo, the Hershey Chocolate Company, and actress Jane Fonda. In a subterranean bunker beneath their house, agents found over 100 military-grade weapons and 27,000 rounds of ammunition stockpiled in preparation for the approaching apocalypse.

What made Wells Fargo, Tarzana a landmark bank job was not the screwballs behind it, but the dipshit at Wells Fargo who let slip to the media the amount taken in the heist: $437,000, the most in L.A. history to that point. Revealing the amount stolen, especially in a major haul like Tarzana, is a big, fat no-no in the banking and law enforcement worlds. Neither want people to know how much money there is to be made robbing banks.

Sure enough, just over the hills in the flatlands of South Central L.A., an Original Gangster from the Rolling Sixties Crips called “Casper,” heard the size of the Tarzana heist and decided that takeover bank robberies might be a good business to get into. Within weeks, Casper was sending armed bands of teenage wannabes and junior gang members bursting into dozens of suburban bank lobbies across the Southland. The FBI quickly had a name for them: “Baby Bandits.”

Unlike the cool and efficient West Hills Bandits, the jittery, undisciplined Baby Bandits, often barely into their teens, introduced themselves with bursts of gunfire, pulling wedding rings off the fingers of terrified customers, and needlessly pistol-whipping bank employees. “Indoor muggings,” Rehder called them. They were young, poor, fearless, extremely dangerous, and terrible at their job. Their droopy drawers fell down while running away. Dye packs exploded on them, police helicopters swooped in on their getaway cars following wireless tracking devices hidden in hollowed out stacks of bills. In addition to bank ceilings, customers, and employees, they sometimes shot each other or themselves. The Bandits were captured in droves, but there were always more where they came from. Meanwhile, Casper was always tucked away safely in some motel room or other meet-up location far away from the action, and the arrests.

In the first nine months of 1991, there had been about forty “takeover” robberies of the “Everyone get on the fucking floor, now!” variety. But once Casper got in the game, that number jumped to over 100 in the last three months of the year. The next year, the number of takeovers, almost all committed by Baby Bandits, soared to 448. In less than two years, takeovers had gone from 4% to 30% of all the bank robberies in Los Angeles. The level of violence associated with robberies spiked accordingly, with each Baby Bandit takeover a volatile and dangerous affair.

There is the potential for violence in any bank robbery, which generally falls into several categories: “note passers,” “capers,” which include vault “tunnelers,” “inside jobs” involving bank employees, and “takeovers.” It’s the takeovers that keep the FBI up at night. The great L.A. bank robbery epidemic, which stretched roughly from 1980 to 1997, was bookended by two spectacular takeover robberies that had nothing to do with cocaine or Baby Bandits but showed just how bad a takeover robbery can go.

***

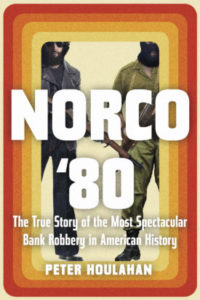

On May 9, 1980, five heavily armed young men led by an evangelical born-again Christian name George Wayne Smith attempted a takeover robbery of the Security Pacific Bank in the Riverside County town of Norco that turned into one of the most violent events in law enforcement history. Like the West Hills Bandits, Smith and his housemate Chris Harven were preparing for a rapidly-approaching apocalypse in which only the well-armed and well-funded would survive. Neither had any previous criminal record, but they did have an elaborate plan that began with stealing a getaway van and kidnapping the driver. From there, just about everything went wrong.

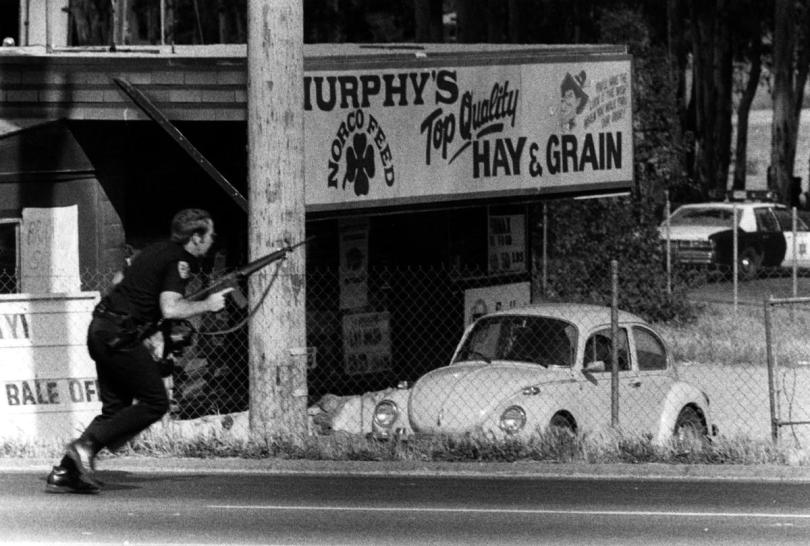

Police responding to reports of bank robbery in Norco.

Police responding to reports of bank robbery in Norco.

The diversion bomb they placed under a gas main of a construction site a mile away fizzled out. Entering the bank in military fatigues and ski masks, armed with assault rifles, they were spotted by a teller at a bank across the street who called the Riverside Sheriff’s Department. Deputy Glyn Bolasky just happened to be stopped at a red light staring directly at the bank when the 211 dispatch came over his radio.

What followed was a ferocious firefight on a crowded Friday afternoon in a major Southern California intersection. With their teenage getaway driver killed, the four remaining robbers carjacked a pickup truck and went on a 40 mile running gun battle through the streets of Norco, onto a busy freeway, and into the mountains above L.A. where they ambushed pursuing police and escaped into the rugged canyons. When it was all over, three were dead, almost twenty wounded including seven police officers, with 33 law enforcement vehicles disabled or destroyed by gunfire and homemade fragmentation grenades, including a sheriff’s helicopter downed over San Bernardino County.

***

At the other end of the timeline, with the number of L.A. bank heists finally decreasing by the mid-1990s, the “Bank Robbery Capital of the World” seemed determined to go out in spectacular fashion.

The two men who robbed the Bank of America in North Hollywood on February 28, 1997 had struck before. Unlike the West Hills Bandits, there was nothing even vaguely humorous or entertaining about Larry Phillips and Emil Matasareanu. The two amateur body builders who had met at Gold’s Gym and shared an adolescent fascination with the 1995 bank heist movie Heat were the FBI’s worst nightmare right from the start.

The two amateur body builders who had met at Gold’s Gym and shared an adolescent fascination with the 1995 bank heist movie Heat were the FBI’s worst nightmare right from the start.The pair began their L.A. robbery career in June of 1995 with the cold blooded murder of a Brinks armored car guard in broad daylight outside a bank in Canoga Park while a dozen of witnesses looked on. They never even gave 51-year-old Herman Cook a chance to hand over the cash, simply opening fire on the man without warning from close range with fully automatic assault rifles and armor piercing bullets. Agent Rehder had a very bad feeling about these two beyond the obvious. “I suspected that these guys weren’t just in it for the money, but for the thrill of the thing.”

Their next job nine months later was as harebrained as it was bizarre. Shooting from the passenger window of a van at a Brinks armored car headed in the opposite direction, they managed to hit the windshield with five rounds but failed to stop it. So they turned around and chased a 10,000 pound armored truck with three armed guards in it for a few blocks before giving up. Switching to a cold car parked a few blocks away, the two torched the van with a delayed incendiary device in a scene straight out of the movie Heat.

From there, they moved on to bank jobs, hitting two Bank of America branches a month apart, the second at the exact same B-of-A in Canoga Park where they had murdered Herman Cook. In each of the heists, they walked away with enormous takes of over three quarters of a million dollars. When FBI agents got a look at the surveillance video cameras, they could hardly believe what they were looking at. Already very large bodybuilders—Matasareanu weighed in at over 300 pounds—the two looked like nightmarish Transformer action figures as they slowly moved about the bank lobby in full body armor, ski masks, and sunglasses, carrying fully automatic AK-47-style assault rifles equipped with 75-round ammunition drums

While inside, they fired dozens of rounds and threatened to kill small children if their mothers did not stop them from crying. They also made rookie mistakes like leaving their getaway car running in the parking lot with the driver’s door open. But what worried the FBI most was the amount of time they spent inside the bank: six minutes on the first, eight minutes on the second, an eternity for a bank robbery. To Rehder, it seemed as though these two guys were just looking to get into a shootout with police.

larry phillips and emil matasareanu

larry phillips and emil matasareanu

If that’s what they wanted, they got it ten months later at another Bank of America in North Hollywood. This time, the two did just about everything a bank robber is not supposed to do. Lumbering down busy Laurel Canyon Boulevard like hulking monsters, they were spotted by a passing L.A.P.D. cruiser who radioed in a robbery in progress. Within seconds, the two officers heard automatic gunfire coming from inside the bank. “The minute we heard the suspect description over dispatch, we knew exactly who these guys were,” said L.A.P.D. Officer John Caprarelli, who wrote about his encounter with Philips and Matasareanu in his book, Uniform Decisions.

Blowing open access doors with dozens of rounds of gunfire, they demanded that every teller drawer be emptied and every last vault and reserve box of cash in the place be opened. The process took an astonishingly long fifteen minutes. On their way out, they took even more time in a failed attempt to blast open an ATM after they already knew the place was being surrounded by cops. When they did finally emerge out the front doors, all the money they did have was destroyed by red dye packs that went off in their duffel bag.

Leaving the ruined money behind, the two walked back to the side parking lot and stood in the wide open firing hundreds of rounds at cops and civilians for over a half hour, making no effort to escape while police rounds bounced harmlessly off their body armor. At last, the two began a slow-motion escape, with Philips strolling beside the getaway care rather than getting inside it. Again, the two seemed more interested in killing cops than actually getting away. Under heavy fire from Caprarelli and dozens of other LAPD officers, Phillips’ Chinese AK-47 knockoff jammed on him. Tossing the disabled rifle aside, Phillips pulled out a handgun, stuck it under his chin and shot himself through the head, the whole thing captured by news helicopters hovering above and beamed live to hundreds of thousands of television viewers nationwide.

Matasareanu was finally felled in a hail of gunfire a block from the bank. When handcuffed by police he told them to “shoot me in the fucking head.” They didn’t have to: Matasareanu was not been wearing armor on his arms and legs this time and had been shot 29 times. He bled to death on scene.

In all, over 1,700 shots were fired, nine LAPD officers and three civilians wounded, 12 police cruisers destroyed and 85 civilian vehicles hit by gunfire. A pair of loners who hid their secret criminal life from even their wives, Philips and Matasareanu took the whereabouts of their $1.5 million in stashed loot from previous robberies to their graves. The money has never been found.

***

The sudden drop in bank robberies in the years following 1992 was almost as dramatic as their spectacular rise the decade before. Prior to the arrival of the Baby Bandits, security was not a major consideration in the overall business plan of the big banks. Spread out among them, losses from robberies were an almost meaningless line item on the annual expense sheet. Even the occasional big heist like the Tarzana robbery was not all that important to the bottom line. “They lose more than that on a single bad loan,” says Rehder.

But after particularly harrowing encounters with Baby Bandits, the banks were starting to see the entire staff of terrorized branch employees quit en masse. The cost of hiring and retraining all new employees to take their place was becoming enormous. And then there were the workman’s compensation claims from the former employees and lawsuits from customers due to post-traumatic stress or actual physical injury. By the end of 1992, losses related to robberies exceeded those from fraud for the first time ever.

Finally, the banks were ready to start listening to the Feds. “We got them all in the same room and began working together,” says Rehder. Soon after, the banks began “hardening the targets.” Plexiglass bandit barriers came back up, doors leading to the vault and teller areas were reinforced, and “access control units” automatically locked vaults and ATM machines so that they could not be re-opened for a pre-set period of time. Some were even equipped to trap the thief inside the vault, which was, in practice, never a great idea.

The increased security began to have a discouraging effect on robbers as the average amount of money scored on heists dropped, especially on takeovers. Others were ratted out for the bigger reward money being offered by banks or identified by photos from new high-resolution bank surveillance cameras. Soon, bank robbery was looking like a lot more risk for a lot less reward.

It just so happened that around this time an extremely controversial policy implemented throughout the federal judicial system several years before began to have its impact felt. The 1989 “Federal Uniform Sentencing Guidelines” all but obliterated a parole system that had been disgorging even die-hard bank robbers back onto the streets an average of three-to-five years after conviction. “The system was a revolving door,” said Rehder. “We were seeing the same guys over and over.” Worse, they were coming out better bandits than when they had gone in. Loaded with bank thieves, the federal prison system was a “finishing school for bank robbers,” according to Rehder. Whatever tricks they did not know outside they learned while inside, emboldening them to continue their career upon release.

The new guidelines allowed for much longer sentences for simple robbery, with stiff “enhancements” for those involving weapons. More importantly, it mandated a minimum of 85% of a sentence be served before eligibility for parole. The customary sentence for bank robbery immediate jumped to 20 years with a minimum of 17 served. Use a gun and you were not going to see the light of day for five more on top of that.

“The greatest bank robbery spree in American history,” as Rehder called it, had lasted three years with Casper, a modern day Fagin, implicated in over 175 bank jobs during which he himself never once stepped inside a bank.While the injustice and negative impact of such sentencing laws can certainly be argued, the effect it had on bank robberies was profound. “Our most prolific and dangerous offenders began to disappear from the scene,” says Rehder. Others began to rethink a career choice that guaranteed at the very least a 17 year stint in Leavenworth. For the addicted, the alternative of thirty days in rehab suddenly didn’t look all that bad.

In 1993, the number of L.A. bank robberies dropped by more than a third to 1,674 from 2,641 the year before. In May of that year, Rehder’s elite bank robbery squad finally took down Casper. “The greatest bank robbery spree in American history,” as Rehder called it, had lasted three years with Casper, a modern day Fagin, implicated in over 175 bank jobs during which he himself never once stepped inside a bank.

From there, the numbers just kept going down as addicts dropped out of the game and the hardcore criminals disappeared into the prison system. The 1994 California “Three Strikes” sentencing law took even more career criminals off the streets for good. The harsh, and even more controversial, federal sentencing guidelines for drug-related crimes, especially crack cocaine, also began to take hold. By then, the raw horrors of crack addiction had stripped away all the glamour originally associated with cocaine and usage began decreasing steadily. By 1997, bank robberies had declined by 70% from their 1992 high.

In the 2000s the numbers were driven down further by even better technology, face recognition software, license plate readers, ubiquitous cell phone cameras in the pocket of every citizen, and surveillance cameras that texted photos of bandits to every cop in the area within minutes after a robbery. “I was flabbergasted when we broke 400,” FBI Special Agent Stephen May told the L.A. Times in 2014. “Then we broke 300.”

By 2013, the number was down to 212, one tenth of what it had been in its worst year. For the first time since the early 1960s, L.A. officially lost its title to the San Francisco Bay Area. It was a shocking change from those years in the early 1990s when the L.A. field office of the FBI had fax cover sheets and coffee mugs emblazoned with the words “Bank Robbery Capital of the World.”

“We’d been the bank robbery capital for such a long run, now it’s passed on to others,” Rehder told the Los Angeles Times the following year. “And quite frankly, they’re welcome to it.”