March 1961

They didn’t realize it as they passed the dice back and forth, but the cowboys from Dallas owned the Bridge Street Club.

Jack Digby drove Polly Barentine up on Cedar Mountain, right outside of town. At the summit of the mountain there was a small parking area where folks would go to “look at the duck.” That’s what kids used to say to their parents, that they were going up there so they could look down on Hot Springs and see the way the streetlights formed the shape of a duck. But that wasn’t why anyone really went up there. They went up there to neck. Jack Digby, however, was a twenty-nine-year-old man with simple needs and singular focus. He wanted to do much more than neck. He was doing much more than necking when Polly’s husband, Everett, showed up.

When Everett got within sight of the car he opened fire. One of the bullets caught Digby in the face. Digby went for his gun in the front seat and managed to get it squared up and aimed toward whoever was firing on him. He returned fire and, being an officer of the law and a practiced marksman, caught Everett several times in the chest and gut. The two men pulled their triggers until both their guns were empty.

Somehow neither man died. Even more remarkably, neither man went to jail over the gunfight. But Jack Digby was kicked out of the Hot Springs Police Department. In a way it was good timing. Digby’s lawyer was Sam Anderson. Sam had just cleared the way for the opening of the Bridge Street Club, and he was trying to line up partners. Digby was the perfect fit for the rival gambling faction. In addition to having connections on the police force, Digby was a prolific hustler. He pimped women off barstools. He ran the bingo games at the American Legion. But Digby had never been content with pimping and bingo money. He wanted to be a big shot gambling boss. He was known as a brawler, someone who’d knock someone’s lights out for looking at him the wrong way. Just like up on Cedar Mountain, he didn’t hesitate to act. Most important, he had a nice chunk of change saved up. He and three other men put up twenty-five thousand dollars apiece to bank the Bridge Street Club’s casino, and just like that, Jack Digby went from disgraced patrolman to distinguished gambler.

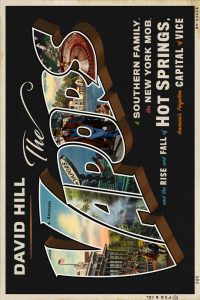

The 1961 race meet was the biggest race meet Hot Springs had ever seen. Tourists crowded the sidewalks. Automobile traffic clogged the streets. The municipal airport, which usually hosted dozens of private aircraft during the race meet, now regularly packed in over one hundred planes. Much of the renewed interest in Hot Springs around the country was due to the opening of the Vapors.

***

Dane Harris’s strategy of running his club as an entertainment venue first and a casino second was paying off. His enormous talent budget was bringing in the best acts from around the country—Marie McDonald, Mamie Van Doren, Gary Crosby, Ted Lewis, Pinky Lee, the Andrews Sisters. The popular singer Frankie Laine even hosted an episode of the nationally broadcast Frankie Laine Show from the Vapors. Entertainment at the Vapors was such a draw in 1961 that the city’s hotels were using the club’s upcoming lineups in their advertisements around the country.

At each and every opening night, Dane and Marcella would dress up their children and put in an appearance. It mattered to Dane that his young children be allowed to come and watch these larger-than-life performers. It was a privilege to have them in Hot Springs. Dane was proud of the culture and sophistication of his new club, and he wanted his family to experience it, to be a part of it. There was no point in waiting until his children were older. There was no guarantee any of this would last that long.

Marcella and Dane’s relationship was the most strained it had ever been. She spent less and less time with him, and more and more time with her friends on the golf course or at the country club dining room. Marcella was an outgoing woman with a big personality. In the beginning of their relationship, she had helped the more reserved Dane relate to other people, dragging him out to clubs to listen to music or dance, or introducing him to other people and forcing him to socialize. Marcella was the charming one, the one who lured people into their orbit, the one who turned acquaintances into friends. Now Dane was a powerful man, and his reserved and stoic manner was no longer a liability. And while Marcella’s intelligence was once a complement to Dane’s own intellect, one of the qualities that initially drew him to her, he no longer depended on it. He had surrounded himself with plenty of smart people whom he respected.

Marcella had strong reservations about Dane’s role as the boss gambler. The gun in Las Vegas was the tip of the iceberg. In the past year, Dane had started taking a number of alarming precautions. He gave his family a curfew. He hired armed guards for their home. He had the local police check on his family when he wasn’t around. Marcella objected to all of this. Dane dismissed her objections, which added to her depression.

Finding no congress with Dane, Marcella withdrew—into their family, into their elegant home, into her own head. She self-medicated with alcohol. She acted out. She argued with Dane, even in public, much to his consternation. On top of all of this, Marcella had heard rumors of another woman, a girlfriend from Dallas whom Dane kept a room for at the Majestic Hotel. Furious, she demanded a divorce. Dane would not grant her one. But his reasons for wanting to stay in the relationship were less love and affection than a practical consideration of his business interests. Splitting up their family wouldn’t look right. He was now a public figure, and he wanted to curate his public image as best he could. “If you’re going to be in business, you have to be the same all the time,” he’d often say. “You can’t have a temper.” He needed to show that everything was under control.

Things were not, however, under control. In their efforts to command the gambling business in Hot Springs, he and Owney had made as many enemies as they had friends. From jealous mobsters in New Orleans and Las Vegas to locals he had put out of business, the list of people with a grudge against Dane Harris was as nefarious as it was long. And though Dane Harris and Owney Madden had never done anything to wrong Jack Digby, his new role running the casino at the Bridge Street Club put Digby and Dane at cross-purposes.

The Bridge Street Club wasn’t anything like the Vapors. It didn’t have marble and brass and glistening chandeliers. It wasn’t a place at which you’d sport tails and furs while watching a piano player lit by a candelabra. It was, however, an impressive gambling den. It was on the second floor of a building at the intersection of Central Avenue and Bridge Street, which had the unusual designation of being the shortest street in America. The stairs leading up from Bridge Street to the casino were covered in heavy shag carpeting, and inside the shag didn’t quit. The floors and ceiling were covered in carpet. The walls were covered with large boards where bookmakers constantly updated the day’s odds and results from tracks all over the country. There were betting windows just like the ones at the racetrack. The loudspeakers carried the call of the race from the Ritter Hotel. There were slot machines, blackjack tables, and a craps table in the center of the room.

The first week the Bridge Street Club was open in 1961, there was no shortage of curiosity about the town’s newest operation. A lot of the wealthy gamblers who usually got off the airplane in Hot Springs and headed straight for the Vapors or the Belvedere with suitcases full of cash found themselves heading downtown and up the Bridge Street Club’s staircase to check out the new addition. One weekend a group from Dallas came in decked out in boots and cowboy hats. But these men weren’t yokels. They were pregnant with oil money and looking to gamble sky-high. Jack Digby cleared out the center craps table for them so they could have it to themselves. The cowboys bought racks of hundred-dollar chips and started shooting. Before the end of the night they were up more money than Jack Digby had in the safe. They didn’t realize it as they passed the dice back and forth, but the cowboys from Dallas owned the Bridge Street Club.

Digby gave his dealer a signal, and the dealer swapped out the dice for a loaded pair. Jack Digby didn’t even stick around to watch it all unfold. A number of the crew from the old Pines Supper Club worked at the Bridge Street Club, including the palm man Jimmie Green, for this very reason. They’d play the string out perfectly. A few more shooters and the cowboys would give Digby all his money back and then some. Loaded dice were supposed to be how crossroaders cheated casinos, not the other way around. The house had a built-in statistical advantage. They just needed to sit back and let the math do the work. But Jack Digby had only a seventy-five-thousand-dollar bankroll. He would need a lot more than math to beat shooters with deep pockets and a lot of luck on their side. And though he’d narrowly avoided disaster that weekend, he was going to need a lot more than a couple of gaffed dice to beat Dane Harris.

*