When I was conducting research for my Speakeasy Murder mysteries, I was surprised to learn that at least forty or fifty mystery plays had been created and performed throughout the decade, most notably on the stages of New York, Chicago, and London. I’d heard of “Chicago” (1926) of course, that wildly successfully play penned by newswoman Maureen Dallas Watkins, which later became a much touted musical and film. A number of these mystery plays were hits, often adapted from novels and short stories and later made into films. Obviously, there was no guarantee of success, however, and several flopped. The ill-fated “Mystery Moon” (1930), for example, tied the record for the decade’s shortest running musical, when it closed after a single performance.

Chicago in particular appeared to be “the happy hunting ground of the thrillers,” as noted by Sheppard Butler, a drama critic for the Chicago Daily Tribune. To get a sense of the numbers, in 1923 he observed that “[s]ix of [Chicago’s] sixteen standard theaters will be devoted to the single business of scaring their patrons within an inch of their lives. No other city is in the throes of such an epidemic. New York, with sixty “legitimate” playhouses has but three of the shockers. Boston has one, and Philadelphia one. They take their terrors in moderation; our appetite for awe appears to be insatiable.” His wry conclusion? “When in doubt they send another mystery play to Chicago.”

Theater critics scoffed at some, but certainly not all, of these plays. They point to a number of reliable, perhaps tiresome, tropes and plot devices apparently common to the genre. Burns Mantle, in his review of “The Bride” (1924), helps us see some of these conventions: “You know what mystery comedies are. They’re plays in which the butler is never what he pretends to be and the smartest secret service agent on the force takes charge of the last act and collects automatics from all the other members of the cast.” (Chicago Daily Tribune, May 11, 1924).

Similarly, in discussing “The Donovan Case” (1926), Mantle tells us that the play “employs most of the tricks of the mystery play trade. There are sly looks and startled looks, blind leads and tipping screens and tipping screens. Now and then there is a feminine screetch, and whenever excitement dies down excuse is made to darken the theater, which always sets an audience buzzing.” (Chicago Daily Tribune, September 5, 1926).

The theater critics also seem tired of the genre’s attempt to startle and amaze the audience, such as when Butler reviews “Rear Car” (1923), a melodrama in three parts by Edward E. Rose. Of this “completely idiotic mystery play” he writes: “Folks, villainous and otherwise, pop out from under the seats [of a railway car] and other likely places, and this one or that is always either disappearing or being murdered. Between murders the ladies of the party change their gowns, preparatory to developing new ecstasies of fright. A gorilla drops in, with electronic lights for eyes, and shortly thereafter steel panels turn the place into a prison, while a portentous voice announced that death waits in the valley below…” (Chicago Daily Tribune Feb 27, 1923, pg. 21).

The detective and the butler were so prevalent that actor Reynolds Denniston, the chief detective in “Whispering Wires,” had the wild idea to create the “stage detectives association.” Not to be left out, this venture was soon followed by the establishment of the “stage butlers association” by Stanley Harrison, who plays a butler in the same play. (Unfortunately, I could find no clues as to what may have happened to either of these associations.” (Washington Post, April 29, 1923, p.64).

However, many of these plays were warmly received by audiences and critics alike, with a few standouts among them:

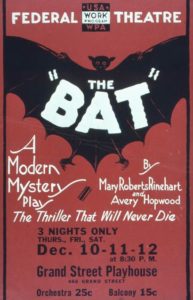

“The Bat” (1920) was one of the most notable mystery plays of the era. Written by novelist Mary Roberts Rinehart and Avery Hopwood, and adapted from Rinehart’s novel The Circular Staircase, the play features a young woman spending a dark and stormy night at a summer home, trying to find stolen money hidden on the premises. The play enjoyed highly successful runs in London, New York and Chicago, and part of the fun and buzz seemed to be about keeping the story line secret. As a Los Angeles critic wrote on February 11, 1923, “Just what ‘The Bat’ is all about—that’s a secret. In fact, wherever ‘The Bat’ has been played, the audience and critics are earnestly requested not to disclose the secret of the story and they never do.” (p. III29). The play spawned three film adaptations, including “The Bat” (1926), “The Bat Whispers” (1930), and “The Bat” (1959), as well as influenced the development of DC comic book character Batman.

Two others were drawn from real-life murder trials, which may have helped their popular appeal. The first of these is “Chicago” (1926). Written by crime reporter Maurine Dallas Watkins, “Chicago” is based on the cases of two women who were tried and acquitted of murder in 1924. It ran on Broadway for 172 performances and had great success in other major cities, including the Windy City. In addition to becoming a hit Broadway musical in 1975, it was adapted to film several times, with a silent version by Cecil B. Demille in 1927, an upbeat version in 1942 starring Ginger Rogers, and a much-acclaimed version in 2002 which won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Similarly, The Letter” (1927) by British playwright and writer Somerset Maugham, was based on a short story he had written about the real-life murder trial that occurred in Kuala Lampur (Malaysia) in 1911, which scandalously captured the imagination of British colonialists. The London production starred Nigel Bruce (of Dr. Watson acclaim) and ran for sixty weeks and lasted on Broadway for over 100 performances. The play was later adapted for film and television.

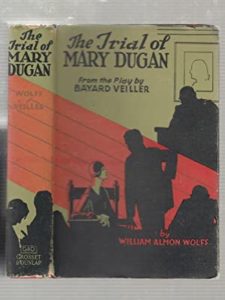

Finally, “The Trial of Mary Dugan” (1927) by Bayard Veiller, an American playwright, is written as a trial, with evidence emerging through the three acts. Throughout, the audience is addressed as if they were members of the jury. The play was also made into a novel by William Wolff in 1929 and adapted for film in 1929 and 1941.

Mystery plays continued to be popular in later decades—Agatha Christie’s works, for example, were waiting in the wings. However, fewer mystery plays were produced overall, most likely due to the rise of the Hollywood film industry. Scripts that might have once been turned into theatrical productions, moved to the silver screen, with several hundred mystery films produced in the 1930s alone.

But there was something special about these early mystery plays that may have gotten lost in translation. Those early mystery plays had it all…characters disappearing through trap doors…fake blood…villain’s eyes that could glow red…detectives who talked straight to the audience. As critic Herbert Moulton commented on the 1924 film adaptation of “Nightcap”: “…[N]othing has yet been discovered which will give hardened theatergoers quite as great a thrill as a darkened stage and fifteen minutes of half-audible whisperings from the lips of spookish players.” (Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1924, B12). The vicarious sensations of these plays, which required a different type of imagination, must have been quite thrilling indeed.

***