There is grim satisfaction in realizing, while sitting safely at your desk in rural Connecticut, that you know more than the Soviet secret police about an event recorded in their own archives. The satisfaction is all the greater when the documents in question concern the identity of a man who planned to strike a powerful blow against the Soviet regime, a man whom the GPU (an earlier avatar of the KGB) saw as one of its most dangerous enemies. In today’s world, punishing a national regime takes a bigger and stronger country, or even an entire alliance, as with the sanctions that the United States and NATO have been imposing on Russia. But there was a time when one determined man tried to do it singlehandedly and came within a hair’s breadth of succeeding.

This story begins in Genoa, the historic port on the Ligurian coast of Italy, where British Prime Minister David Lloyd George proposed holding an international conference from April 10 to May 19, 1922, to discuss the economic reconstruction of Europe after the Great War, and how to improve economic relations between Communist Russia and the Capitalist West. Lloyd George’s inclusion of Russia was a contentious decision in the view of France and some other countries because it implied de facto recognition of the Bolshevik regime at a time when none of the major European powers had yet recognized it. (Similarly, the French had been reluctant to include Germany, which they still saw as a pariah.) However, the Soviets were eager to participate, and the conference was crucially important for them because it would mark the end of their international isolation and promised to provide much-needed foreign capital. The country’s economy was devastated following the Russian Civil War, and the Bolshevik regime’s barbaric policy of grain confiscation aggravated a famine that affected some 35 million people and killed over 5 million.

The remarkable man who put himself in the way of the Bolsheviks was Boris Savinkov. Although he is largely forgotten outside Russia today, he was famous, and notorious, around the world during his lifetime (1879-1925). A complex and conflicted individual, he was a revolutionary terrorist who fought tsarist autocracy, a scandalous novelist, a friend of epoch-defining artists like Modigliani and Diego Rivera, a government minister during the revolutionary year 1917, and an advisor to Winston Churchill. He understood more clearly than most the threat that Lenin and the Bolsheviks represented to his ideal of a democratic, humane and enlightened Russian republic, and became their uncompromising opponent long before they staged their coup d’état in November 1917. He then fought them tooth and nail for seven years afterwards.

The Soviet delegation to Genoa was headed by Georgy Chicherin, the new regime’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs, and Savinkov’s plan was nothing less than to ruin the conference by killing Chicherin so that negotiations could not even begin. The outrage this would cause in Moscow would be a major setback for both the Soviet leadership and for Lloyd George’s hopes of integrating Russia into the life of Europe. It would also be a step forward in Savinkov’s ultimate plan to overthrow the Soviet regime.

To prepare the ground for the international scandal he wanted to cause, on Friday, April 7, 1922, the day after the Soviet delegation arrived in Genoa, Savinkov published an open letter to Lloyd George in the London Times in which he berated him for wanting to negotiate with the Soviet leaders rather than treating them like the criminals they were. He also made a thinly veiled threat, and in effect threw down the gauntlet to the Soviets and the Western security services guarding their delegation, by referring to the “compliment” the Soviets paid him by “regarding me as one of their most implacable enemies.” To someone like Lloyd George and Mansfield George Smith-Cumming, the legendary, monocled, one-legged head of MI6 in London known as “C,” who knew Savinkov’s reputation well, the implications of his remark were clear and precautions had to be taken to stop him.

The British government’s wheels began to turn in response. On the same day that Savinkov’s letter appeared in the Times, London telegraphed its Passport Control Office in Rome and requested that the Italian National Police be informed that Savinkov appears to have summoned several known Russian anti-Bolsheviks from Prague to Genoa “to commit terroristic acts against delegates of the Soviet government.” The telegram included the name of the man heading the group and described his physical traits. But there was nothing specific in it about Savinkov himself.

The Soviets also went into high alert. By the beginning of 1922, the GPU had begun to watch Savinkov with increasing attention and growing alarm. They had accumulated an enormous amount of material (still preserved in the archives of the FSB, successor to the KGB) showing that he was one of the most active anti-Soviet leaders in the emigration, and that fighting him would require great effort and resources.

But they did not know the half of it, because it would also require great imagination. For Genoa, Savinkov developed the most ingenious terrorist plot up to this point in his life. He intended to hide in plain sight and gain access to the Soviet delegation through their own back door. And for this he would need a special kind of disguise and document.

*

The primary burden of safeguarding the international delegations in Genoa necessarily fell on the Italian government, which took extraordinary precautions. An American newspaper reported that even before the conference began the police cleared out the city, raiding various “night haunts” and arresting 1,400 men and women who they thought might “molest or annoy” the visitors—criminals, fugitives from other cities, suspicious foreigners without papers, and beggars.

Tensions around the Soviet delegation were especially high. For security reasons and because of their delegation’s size they were not housed in Genoa itself but in Santa Margherita Ligure, a resort town on the coast fifteen miles to the east, near Rapallo (which would give its name to the important treaty that Soviet Russia and Germany signed on April 16, 1922). As the New York Times proclaimed, “Never even in the great days of Nihilism were the movements of the Czar of all the Russias so hedged about with precautions and secrecy as are those of his successors—Tchitcherin, Joffe and Litvinoff.”

When the delegation arrived by special train on the morning of Thursday, April 6, the four hundred yards between the station and the hotel were lined with Italian troops. The grounds of the Imperial Palace Hotel where the Soviets stayed (the Italian Communist Party did not fail to comment on the irony) were surrounded by a high wall and guarded by agents of the GPU and Italian carabinieri. Because the distance between Santa Margherita Ligure and Genoa seemed to create an opening for a terrorist attack, the Italian government arranged for the delegation to shuttle back and forth in a luxurious saloon car attached to a special train, one that would approach the conference site, the Royal Palace, on a private line that did not pass through city streets. And, as a final precaution, the Italian authorities even removed over two hundred Russian émigrés who were living peacefully in the small town of Nervi on the coastline between Rapallo and Genoa through which the train would pass.

*

But Savinkov’s plot to assassinate Chicherin in Genoa was not only the most ingenious one he hatched during his incredibly active life; it is also the second-most enigmatic (his final plot in 1924 is the most mysterious) because of the nature of the surviving documentation. The vast trove of documents about Savinkov in the FSB archive in Moscow is now closed to researchers. Nevertheless, something is known about the documents pertaining to Savinkov in Genoa because a very brief overview of them was published by two Russian historians who were allowed to peruse them when the archive was briefly opened. And despite the brevity of their overview (whose accuracy there is no reason to doubt), it is very striking that these documents do not refer to the most surprising aspect of Savinkov’s plot in Genoa.

To understand what is missing and how original Savinkov’s plan was, it is necessary to turn to Italy and several dozen documents in the Central State Archive in Rome (access to which is not restricted). When taken together, and despite some remaining lacunae, the Russian and Italian sources sketch a fantastic plot. But it is one that the Soviet secret police do not appear to have fully understood.

Genoa was in a state of feverish excitement during the conference and the streets in the center were crowded with more kinds of security personnel than anyone had ever seen before—police in frock coats, gendarmes in operatic tricornes, guardsmen, soldiers in full military gear, and even airplanes flying overhead. In order to evade all the security agents who were looking for him and defending his Soviet target, Savinkov decided to assume the identity of another Russian who had also come (or been summoned) to Genoa—one, moreover, of similar build and whose face looked very much like his own, at least from certain angles. This important fact—that Savinkov found an actual physical “double”—is not mentioned in the short summary of FSB documents about Genoa, which simply refers to his assuming a fake, paper identity (and which Savinkov had done routinely for years during his earlier plots). From the available evidence it also appears that the FSB archive has neither copies, nor any other knowledge, of the Italian archival documents about the confusion that the physical resemblance between Savinkov and the Russian would cause the Italian police and that almost allowed him to get away with murder.

The man Savinkov chose as his double was an émigré from Constantinople (where some two hundred thousand Russians, including the remnants of the “White” Army, had sought refuge from the Bolsheviks during and after the Russian Civil War, 1919-1923). He arrived in the Italian port of Brindisi in early February of 1922, and travelled to Rome before coming to Genoa. In Italian sources his name is given as “Elia Golensko Gvosdovo,” or “Gvozdavo-Golenko,” in addition to other spellings. In Russian sources his surname is simply “Gulenko.”

Gulenko came to Italy as a journalist with an interest in religion. He presented himself as a former member of the Orthodox Church who had converted to Catholicism and written a book urging conversion, and who had a connection to an Apostolic delegation and the Vatican. But this may have been a cover because there is some evidence suggesting he had a connection to Generals Denikin and Wrangel, both of whom were still involved with Russian émigré military organizations hoping to resume the fight against the Bolsheviks. He also had a connection to General Anatoly Nosovich, who was a notorious “White” agent in the Red Army during the Russian Civil War. Very little else about Gulenko is known.

Why Savinkov decided to assume Gulenko’s identity is clear enough because of the physical resemblance between them; but how he did so is not. It is possible that Savinkov acted without Gulenko’s knowledge or cooperation, although in the past Savinkov had always taken great pains not to compromise the owners of the papers he borrowed as parts of his disguises. Using another person’s papers and identity can also cause obvious problems when both people are in the same place. But it is also possible that Gulenko was in some way connected with Savinkov’s plot and was an accomplice or a decoy.

Whatever the case, by pretending to be the journalist Gulenko, Savinkov was able to establish contact with no less a personage than the GPU’s Station Chief in Italy. To win the man’s confidence, Savinkov passed himself off as a Bolshevik sympathizer, gave him a number of confidential documents of mostly historical significance that he probably got from his own archive, and in a crowning gesture of bravado offered his services to the GPU. The Station Chief fell for it and met with Savinkov on several occasions. Savinkov’s charade progressed so incredibly well that he was almost included in the team of Soviet guards assigned to protect Chicherin and the rest of the delegation.

Had Savinkov succeeded in killing Chicherin, it would have been the most significant assassination of his life in terms of the actual consequences.

But then something happened and the plot was spoiled. On or shortly after Tuesday, April 18, Savinkov was arrested by the Italian police as he tried to force his way into the Imperial Palace Hotel where the Soviet delegation was staying. He presented papers showing that he was Gulenko, and since he had established a relationship with the GPU by using this identity, he must have thought that they would lead to his release.

However, chance and the GPU’s alertness spoiled his plot. With the help of a local police officer, agents of the GPU in Berlin managed to get a copy of the temporary identification papers that Gulenko had been issued by the Italian consul in Constantinople and that Savinkov had used to travel to Italy from Berlin. These papers included a photograph of . . . .

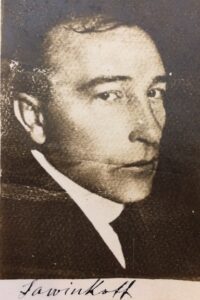

The two Russian historians who summarize what they read in the FSB archives say it was a photograph of Savinkov. But this is very doubtful because the GPU was unaware that Savinkov had a “double” in Genoa and consequently had no reason to try to distinguish the two men physically. Supporting this conclusion is that the man in a photograph the historians did include in their volume of selected FSB documents (which focus on Savinkov’s death) is misidentified as “Savinkov . . . photographed in prison in Genoa.” Even from the vantage point of rural Connecticut, it is clear that the man is Gulenko.

The photograph that the Soviet agents obtained in Berlin was sent to the GPU Station in Italy and, not surprisingly, initiated a period of great confusion on the part of both the GPU and the Italian authorities as they tried to figure out if the detained man presenting himself as Gulenko was actually Savinkov.

This confusion was compounded by the arrest in Genoa around the same time, Tuesday, April 18, of the real Gulenko on suspicion of being the notorious terrorist Savinkov. He naturally insisted on his innocence, leaving the police with the quandary of figuring out who was who. They took the new prisoner’s fingerprints, but this could not resolve the matter because Savinkov’s were not immediately available for comparison. The police were left with relying on photographs and on people who thought they knew what Savinkov looked like.

Because the one photograph of Savinkov in the possession of the Italian police showed his face at a ¾ turn, they photographed Gulenko from the same angle for comparison. In these photographs (see below) the two men resemble each other to a considerable extent, so that only someone who knows them well could tell them apart (among other features, their ears, earlobes and nostrils are noticeably different). In full face photographs their resemblance is not nearly as close.

(L) Savinkov. (M) Gulenko, who was made to pose in a way that matched the photograph of Savinkov; this is a copy of the same photograph that was misidentified in the volume of documents from the FSB archive compiled by the two historians. (R) Gulenko full face. Ministero dell’Interno, Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome.

Gulenko’s photograph was shown to several Russians in Italy, including the Soviet Ambassador in Rome and members of the Soviet delegation in Genoa. All of them confirmed that the man in the photograph was actually Savinkov. However, Italian experts on photographic identification were not convinced and sent Gulenko’s photograph to Edvard Beneš, the Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia because he knew Savinkov personally, and to the French Foreign Ministry, because it was known that Savinkov had lived in France. Both denied that it was Savinkov.

It took several days, but by Saturday, April 22, the Italian investigators had figured out the truth with the GPU’s help. Savinkov was already in their custody and the following day they arrested four of his confederates, who were found to have a plan of the Imperial Palace Hotel in their possession. As for Gulenko, the GPU apparently remained ignorant of his actual existence.

The Soviet regime was delighted that Savinkov had been arrested and tried to have him extradited to Russia as a major terrorist and criminal. They reasoned that putting him on a show trial in Moscow would generate useful propaganda and be far more “civilized” than having him killed abroad, which would harm the regime’s reputation.

However, the attempted extradition failed, and by the end of April, Savinkov was back in Paris. It is likely that someone with connections—perhaps Mussolini, whose power was rising, and who had met with Savinkov a month earlier to discuss an anti-Bolshevik alliance—had pulled strings on his behalf. In June, the Italians allowed the real Gulenko to take a ship from Naples back to Constantinople, despite their lingering suspicions about him.

As a direct result of how dangerously close Savinkov came to assassinating Chicherin, and what this augured about other attacks he could stage on the regime’s representatives when they went abroad, the Soviet secret police decided that he had become an intolerable threat. On May 6 to 8 the GPU Directorate met in the Lubyanka headquarters building in Moscow and established a new Counterintelligence Section specifically to combat him and his ilk.

*

That the GPU was unaware of the full extent of Savinkov’s plot in Genoa is a credit to his cunning as a conspirator. Moreover, knowing what the GPU missed provides a modicum of schadenfreude, which is not a trivial feeling considering the organization’s bloody role in one the worst regimes in the twentieth century. But knowing about Gulenko’s mysterious involvement does not change how Savinkov was thwarted and Chicherin escaped. And unless a cache of previously unknown documents is discovered or revealed somewhere someday, we may never understand any more about what additional ingenious twists Savinkov might have had in mind.

However, Savinkov’s experience in Genoa does resonate in a curious way with the last great plot of his life two years later, when he conspired to be captured by the Soviet secret police, and made headlines around the world by proclaiming that he accepted the Bolshevik regime. A close reading of the relevant published documents, drawn from both Soviet and other sources, strongly suggests that he was actually trying to deceive his captors under the guise of colluding with them, and that he intended to shake the regime by assassinating one of its leaders, if he could succeed in being released. Part of the evidence for this inference is that during his notorious show trial he repeatedly lied about his past, and when asked about his plot against Chicherin, replied “I was absolutely never in Genoa. It’s a mistake that I was supposedly there.”

Why would he have said something so egregious? Perhaps to bolster the illusion that he had renounced his former life and joined the Bolsheviks; or, in terms of his plot in Genoa, created a compliant “double” of himself to conceal his true nature and commitment to striking one last blow against the tyrannical regime.

________________________________________________