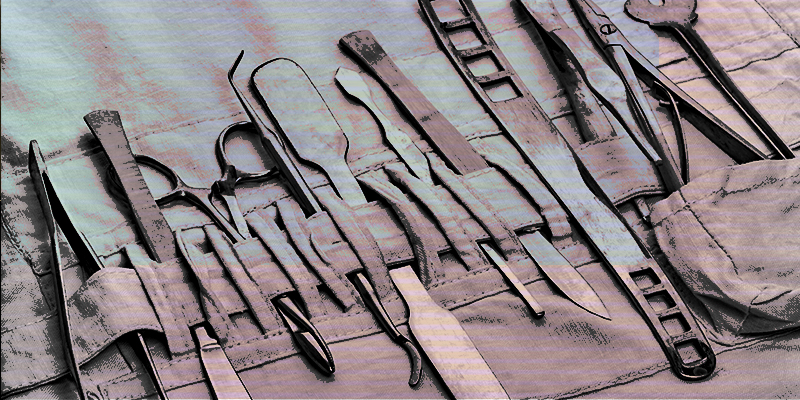

Imagine you’re an ambitious doctor in 1820’s Edinburgh. You don’t know anything about germs or anesthesia, but you have a medicine chest of calomel, blue pills, mercury and arsenic. You lance and bleed and carry a bag with all kinds of scalpels, forceps and syringes. Unlike the men you apprenticed to—army doctors, because you couldn’t afford university—you also carry a hollow wooden tube, a controversial innovation called a stethoscope. Many of your colleagues still listen to patients’ hearts putting their ears right on their chests, but this makes some women uncomfortable. A stethoscope gives better sound and protects their modesty.

You can amputate a leg in under five minutes, but unfortunately, that’s not enough to make a name for yourself.

Unlike some of your teachers, you have an astonishing knowledge of human and animal anatomy. In the last few decades, dissection has become a thing. You’ve taken apart dozens of dead bodies: men, women, children, pregnant women (these bodies are particularly expensive), rabbits, dogs, birds, even a platypus. You’re so good at dissection, one of these animals, carried across oceans and seas, was presented to you to disassemble in a public theatre. Other doctors are jealous.

Most of your income is made cutting apart dead things and selling tickets.

But dead things, astonishingly, are in short supply, and unless you have them, you can’t sell tickets.

This was the quandary of Dr. Robert Knox, of 4 Newington Place, Edinburgh. Like most of his colleagues, he counted on resurrection men, nighttime marauders with prybars and spades, to supply him with bodies stolen from local kirkyards.

Edinburgh was (and is) a leading centre for medical study. In Knox’s lifetime, numerous private anatomy schools offered classes and specialist lectures as well as the university. Knox himself taught hundreds of students each year and was known for the excellence of his lectures as well as his reliable supply of specimens for study. But everyone knew it was impossible to come by so many honestly.

On October 31, 1828, Knox’s suppliers, the infamous William Burke and William Hare, murdered their last victim, Margaret Docherty. In exchange for immunity from prosecution, Hare confessed that he and Hare killed sixteen people and sold their bodies to Knox over a ten-month span.

Burke was hanged and publicly dissected, but Knox was never called to testify. The medical fraternity, rightly concerned for their reputation, closed ranks to shield Knox, though Robert Christison, a physician and leader in the emerging field of forensic science, said that he considered Knox “deficient in principle and in heart.”

He certainly was. Though Knox may not have suffocated any of the sixteen known victims, their murders would not have happened without his greed, ambition, and appalling lack of compunction. But Robert Knox and the so-called Burke and Hare murders are not the only medical murderers worth mentioning. Cases of ‘Angels’ and mercy killers such as Charles Cullen show how vulnerable we truly are to ‘good’ nurses and doctors.

For example:

Dr. Harold Shipman, a UK physician, killed 218 patients (confirmed) but may have murdered as many as 250. All were female and elderly, and he was convicted of killing only 15.

Elizabeth Wettlaufer, a Canadian nurse, killed 8 long term care residents.

132 patients of Dr. John Bodkin Adams, an Irish GP practicing in Britain, died in comas between 1946 and 1956. Though charged with murder, Adams was never convicted. He was struck off the medical register in 1957 but reinstated in 1961.

These cases, and the personalities of Knox, Wettlaufer, and Adams—their astonishing immunity to detection and prosecution—are the inspiration of my new novel, The Specimen, a story I hope readers find as haunting as the truths that inspired it. Because we trust the women in the white coats and the men holding the stethoscopes. Or at least we tend to.

But maybe, sometimes, we shouldn’t.

***