For a country with a virgin queen, Elizabethan England was just stewing in sin. Or maybe it only seems that way from society’s portrayal in the books, plays, and pamphlets of the period. Maybe those authors, playwrights, and publishers understood the timeless craving for true crime stories, and happily fed people’s appetites. Whatever the reason, if you know where to look, there’s a wealth of material for anyone hoping to indulge in stories of rogues, witches, and knaves.

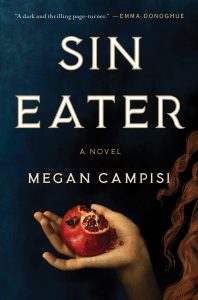

My debut novel, Sin Eater, is a historical mystery set in an Elizabethan England flush with true crime. One young woman is condemned to bear her town’s sins as a sin eater, but she turns her curse into an unexpected source of power when she uncovers and sets out to solve a series of gruesome murders. In crafting the world, I drew on true crime stories of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras. So, where did Elizabethans go for their true crime fix? Here’s a guide to seven delicious sources to transport you to the Elizabethan criminal underworld.

1. The Complete Cony-Catching (1592)

Robert Greene

Robert Greene’s tell-all pamphlets are a perfect starting point for descriptions of cony-catchers*, fool-takers, crafty mates, subtle companions, notorious varlets and their outrageous con games. Pamphlets functioned a bit like tabloid sites do today: cheap to produce, agilely responding to public mood, and ostensibly journalistic. Greene’s pamphlets were intended to “discover villainies,” like the methods of thieves called courbers who stole apparel and other household items out of open windows with extended hooks. Greene even describes a precursor to the letter bomb in which needles fly out of an opened envelope “as forcibly as if they had been blown by gunpowder.”

*Confidence men. Cony, meaning rabbit, is slang for the con’s victim.

2. A Caveat for Common Cursitors Vulgarly Called Vagabonds (1566)

Thomas Harman

Go to Harman’s pamphlet for a catalogue of criminal types and their trades, as well as a “lewd, lousy language of these lewtering lusks and lazy lorels” (thieves’ lexicon). His list includes priggers of prancers (horse thieves), bawdy-baskets (female thieves/prostitutes disguised as trinket sellers), and counterfeit cranks (people who pretended to be epileptics for alms). While Harman claimed to empower the public by exposing criminal secrets, questionable investigative techniques and the popularity of his pamphlets suggest entertainment was also on his mind.

3. Demonologie (1597)

King James I of England

How do witches and necromancers differ? James I was happy to elucidate. This is the book for a 16th-century perspective on witches and their craft. Demonologie describes dark magic of the time, such as thickening the air to obscure sight, concocting powders to inflict disease, and brewing “uncouth” poisons. James I was a staunch supporter and judge of witch trials, and his Demonologie is reputed to have inspired the witch scenes of Macbeth. Oh, and witches are the devil’s slaves, while necromancers are the devil’s masters—and both, James I noted, indulge often in pleasures of the flesh.

4. The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584)

Reginald Scot

Think of this as the Elizabethan precursor to a “Magic Tricks Revealed!” site. In contrast to James I’s work, The Discoverie of Witchcraft offers an exposé of certain supernatural acts commonly attributed to witches (and places credit for others where Scot thought it belonged: with the divine.) In delightful detail the book unmasks several famous magic acts of the time, like “John the Baptist,” in which a decapitated body and its severed head appear to remain alive. While James I was rumored to have burned all copies of the book when he ascended the English throne, thankfully, he didn’t succeed.

5. The Discovery of a London Monster, called The Blacke Dogg of New-gate (1638)

Attributed to Luke Hutton

Cannibal prisoners. An incarcerated wizard. The monstrous specter of a black dog. For your paranormal true crime fix, look no further than this ghost story, attributed to Newgate Prison inmate Luke Hutton. The story follows a scholar with occultist leanings who is imprisoned during a famine. Unable to fend off his ravenous fellow prisoners, the scholar’s spirit returns after his death to seek revenge on his killers, appearing as a “black cur ring’d about the nose with a golden hoop . . . two saucer-like eyes and an iron chain about his neck.” Part informational pamphlet, part poem, and part morality tale, Hutton’s story redoubled Newgate Prison’s already harrowing reputation.

6. The Roaring Girl (circa 1611)

Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker

It’s not reality T.V., but this play definitely has similar appeal. Real-life cross-dressing cutpurse, pimp, and bawd Mary Frith inspired the main character of Middleton and Dekker’s “city comedy.” Attempting to show more gritty realism than Elizabethan precursors, plays like The Roaring Girl looked to the local underworld for source material. In fact, the real Mary Frith is reputed to have performed at the Fortune Theatre around the same time The Roaring Girl was in production there. Historians believe she might well have played herself onstage.

7. The Alchemist (circa 1610)

Ben Jonson

Our scene is London, ‘cause we would make known,

No country’s mirth is better than our own.

No clime breeds better matter, for your whore,

Bawd, squire, imposter, many persons more

If you’re hankering for more than a list of con games, Jonson’s play will stage the scams for you. The Alchemist follows three cons as they dupe victim after victim. In writing his fictional play, Jonson took inspiration from real-life grifters around London. Subtle, the “alchemist” of the title, was probably based on Simon Forman, a self-professed prophet, diviner, and quack of the era (who may have used his own divining skills to ascertain whether women would sleep with him). The play’s scams are pulled from local con games, such as conjuring spirits to assure success at gambling and offering introductions (for a fee) to generous faerie royalty.

Hungry for more? Check out The Elizabethan Underworld by Gamini Salgado (Rowman and Littlefield, 1977) and Rogues Vagabonds and Sturdy Beggars, edited by Arthur Kinney (University of Massachusetts Press, 1990)