Like most people who grow up to be writers, I went through childhood with the constant feeling that I had one less layer of skin than the other kids. My mind was sticky, and I tried my best to dodge most of what the world threw at it. Each summer, my parents and I would leave our home in San Francisco’s Castro District so we could spend hot, thunderstorm-filled days in the sprawling suburbs of Dallas, Texas, time spent in the company of relatives whose emotional restraint and apparent ease with the aspects of life I found anxiety-inducing—Yard work? We might uncover a snake!—made me feel even more like an alien stranded on this planet.

My mother and father left Texas for San Francisco soon after graduating high school, both chasing dreams of becoming professional writers. Decades later, as their ambitions were being realized, their only child was a strutting, lecturing, protesting, chest-beating product of the Bay Area in the mid-1980’s, the proud student of a lesbian-run Montessori-style school that dismissed letter grades as hierarchical engines of soul-killing competition, and started each day of classes with a round-robin session of “sharing” that vaguely mirrored the format of a 12-Step meeting. At an age when most children were being introduced to team sports, my idea of a school field trip was linking hands around the Capitol Building to protest the CIA’s suspected involvement in the La Penca bombing in Nicaragua. I talked a mile a minute, mostly about drama-filled scenes from my favorite movies and television shows, and I discussed them as if the characters in them were as real as my classmates and teachers. My mother would often ask me to slow down so she could be sure I was detailing an episode of Dynasty and not something that had happened at school. The Rices of Texas, by contrast, seemed to operate at about half my speed, and with a quarter of my emotional mood swings. Up until his death from brain cancer in 2002, my father could do an impersonation of a phone call with his mother that would reduce most of our family members to stitches. It went like this. He’d open with, “Hi, Momma. How you doing?”, to which she’d swiftly respond, “Oh, I’m fine. I’ll let you go now.”

And so, sporting a rat tail and draped in baggy tie-dye T-shirts, I would arrive in the Dallas Metroplex each summer possessed of a level of self-actualization (and self-righteousness) that most would find bracing in a grown man, let alone an eight-year-old.

Texas never seemed ready for me, and I was never quite ready for Texas.In other words, Texas never seemed ready for me, and I was never quite ready for Texas.

Almost instantly upon my feet hitting the ground at DFW Airport, the prairie stoicism of my father’s family engirded me in constant exhortations to not talk quite so much and to “not be so sensitive”. Both dictums felt insurmountable. I vividly remember looking up one day during some lecture I was delivering at the children’s table to see a cousin of mine had stuffed little bits of paper napkin into his ears to muffle the sound of my apparently unending words. True to form, I sobbed theatrically and ran from the room, my grandmother’s by now familiar admonishment, “Don’t be so sensitive, Christopher”, following me out of the house. This is the part of the story where my mother likes to cut in and remind me that same cousin showed up at our door to apologize moments later and the two of us spent the afternoon in my room reading comic books aloud to each other. Still, the basic fact remains the same. In the Texas of my childhood, I was the tornado blown in from the West Coast, upsetting the orderliness of the Rice family’s quiet life on the shores of Cedar Creek Lake.

As if all this weren’t noisy enough, when faced with a visual trigger that mirrored something I’d seen in a scary movie, I would immediately devolve into hysterics. During a school trip to a Northern California lake around this time, I had to be carried screaming to shore when I realized the inflatable yellow raft we’d just set out in was starkly similar to one the giant killer shark devours in Jaws 3. “Your parents should not be letting you watch those movies,” I remember one teacher wailing as I writhed in her arms like a worm on a fishhook. But my father was insistent that adolescence and it’s resultant bursts of hormones would cure me of these episodes, and my mother believed there were too many benefits in cultivating a vivid imagination for them to aggressively police the pop culture I consumed . And both of my parents would frequently reassure me that while a vivid imagination might seem like a curse when you’re young, one day it could be a strength. Or an income stream.

Sometimes the images that triggered my meltdowns weren’t intended to be frightening at all. I remember the frustration in the voices of my Texas kin as they tried to explain how the brief glimpse we’d been given of Cheech Marin hollering and trapped inside of a working dryer in the commercial for his new film was supposed to be comic, not a scene of gruesome torture.

But nothing held a candle to the poster in the window of the video store we had to pass during our frequent drives between Dallas and my grandparents’ lake house, a totem of such paralytic terror I had to hide under the backseat of my aunt’s van until she assured me we’d left the store in the dust. In it, the cannibalistic, buzz saw-wielding Sawyer family posed for a gruesome family photo beneath the blood dripping words The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. I hadn’t seen one frame of the film (I still haven’t), but had managed to extract some of the specifics of the plot from a relative—a family of lunatics that killed and ate people. And they lived in Texas! Were they our neighbors? The line between fantasy and reality—already razor thin in my young mind—seemed to shrink even further. Even now, years later, I can still picture that lone video store on the side of a four-lane highway, beneath a huge sky piled high with cumulous clouds. It’s an image that embodies so much of my response to Texas at that age, a place of vast mystery, studded with frequent stark terrors, where the price of admission was a form of silence and restraint that challenged my nature to its core.

In retrospect, there’s a dreadful irony to my having made Texas the center of so many of my childhood fears. In our neighborhood back home, in a city where I felt considerably more valued and understood, a very real monster was gathering force and claiming victims, first made evident by the grown men lining up to buy diapers at the Walgreen’s on Castro Street and the stores throughout our neighborhood that were suddenly closing without notice because the owners had become rapidly and terribly ill. But even after it was given a name, AIDS seemed like an adult horror, whereas Leatherface’s buzz saw, despite being a Hollywood invention, looked capable of slicing through generational divides.

I chose to see sadistic monsters where others just saw shadowy roadsides because shadows alone don’t produce a hot, enervating rush of adrenaline.Around this time, a loving aunt identified my propensity for fearful outbursts for what it was—an aversion to boredom that was turning into an addiction. I chose to see sadistic monsters where others just saw shadowy roadsides because shadows alone don’t produce a hot, enervating rush of adrenaline. After all, wasn’t I the one who’d asked just enough questions of my relatives about the plot details to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 to fuel my nightmares? If this is true, and I believe it might be, then it was the symptom of a larger addiction, an addiction to fantasy, specifically movies and television. The more spectacular and dramatic the action on screen, the more my guard came down, and I went from feeling like I lacked a layer of normal skin, to trying to shed the remaining ones so I could merge with what I was seeing. When the lights went down and the first frames of film began to play, my often debilitating emotional sensitivity transformed from a disability into a passport to potential ecstasy. If I picked the right movie, that is. I wasn’t just in love with the images on screen; I was vulnerable to them, beholden to them, and at eight-years-old, I was painfully learning which ones triggered an excited thrall and which ones brought on a full blown panic attack. Disaster movies, mostly from the 1970’s, ended up providing the perfect blend of dazzling spectacle, high stakes drama, but without the rageful, mutilating sadism that defined the slasher film in the 1980’s. Because as childlike and irrational as it might have been, a moral point of view was being seeded in me at the time, and it’s stayed with me ever since.

Sadistic monsters who desire the suffering of others for its own sake are an abomination unlike any other. This is not to diminish the crimes of the murderer who does not abduct and torture, but the one who does steals their victim’s humanity along with their life. And like so many children who were assured “it’s only a movie”, I went on to read numerous articles detailing how real-life serial killer Ed Gein inspired the creation of the very Sawyer family who seemed to menace me from that video store window. I’m now forty-two and just the other day a writer friend of mine, a veteran journalist who covered a fair amount of hard news, described the extent to which he’s still haunted by what he saw inside the case file for serial killer William Bonin, who tortured and murdered young men throughout Southern California during the late 70’s and early 80’s.

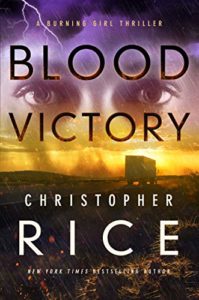

As formative as those Texas summers were on me creatively, it would be years into my career as a novelist before I would invent a heroine who seemed capable of targeting the type of killer whose Hollywood reflection I learned to both fear and despise as a young boy. And when I did, I knew she’d need to have one foot in the world of comic book superhero stories if she was going to truly punish those monsters in the way I deemed fitting. The Burning Girl series is what they call a genre mashup, my attempt to send the hard bitten heroes and heroines of the crime novels I love in pursuit of the Hollywood slice-and-dicers who menaced my nightmares. But in order for my heroine to succeed, she’d need a tool at her disposal, a drug that turned her fear into a sustained burst of superhuman strength, and an organization behind her with an obscene amount of resources.

It wasn’t until the third and most recent entry in the series, Blood Victory, that I allowed the story to take me back to Texas, where I was forced to assess the extent to which those summers in the 1980’s not only crafted the series, but my perspective as a writer of tall tales. In it, my heroine’s target is a family of psychopaths who have concocted a diabolical method for vanishing their victims and permanently stealing their voices. Following the through line from Cedar Creek Lake to the pages of my most recent novel doesn’t require a therapist’s eye. But disclosing the other connections between the series and my childhood carries some measure of discomfort.

Those of us who write about monsters both human and otherworldly want to believe we’re peeling back the layers to reveal something primal and dark, and essential to our understanding of human existence. But the blanket dismissals of our genre—and our genre mash ups—paint us as arrested adolescents who put horned demons in closets when we should instead be writing thoughtful meditations on the characters whose clothes actually hang within. Admitting that a novel you wrote in your forties was fueled by some incident, preferably traumatic, implies a certain degree of literary sophistication. But admitting your current novel is in large part a wishful fantasy dreamed up to comfort a much younger version of yourself who hid under the backseat of a car to avoid the sight of a movie poster risks your marginalization at the hands of self-described serious artists.

Oh, well. If there’s one thing I still have in common with my eight-year-old self, it’s that neither one of us is very good at fitting in with the crowd. And neither one of us can bring himself to watch The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2.

***