The more you look, the more you see.

Take the paintings of the Belgian Surrealist artist René Magritte. They draw you in, distort your perception of reality, make you question what you are perceiving.

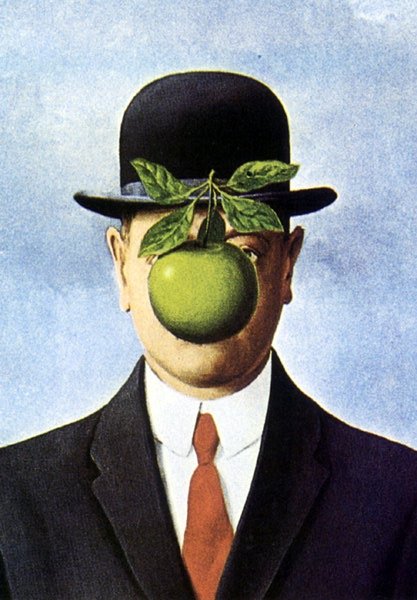

In 1963 Magritte painted The Son of Man. His take on the self-portrait features a lone man wearing a red tie and a bowler hat (a frequent motif in Magritte’s work), while a green apple partially obstructs the subject’s face. We glimpse the corner of his left eye. Even with the knowledge that this is the artist himself, we still see him as faceless and without identity.

Of his painting, Magritte said:

“At least it hides the face partly. Well, so you have the apparent face, the apple, hiding the visible but hidden, the face of the person. It’s something that happens constantly. Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.”

Article continues after advertisement

The push-and-pull between concealed and revealed is always exciting in crime films. There is great excitement in witnessing the role-play of dual identities, secret personas, and shifting allegiances. There is also great entertainment in seeing something very familiar, be it a piece of pop culture or artwork, functioning as a tool to wield power and corruption. In John McTiernan’s 1999 remake of The Thomas Crown affair, Thomas Crown (Pierce Brosnan) utilises The Son of Man’s anonymity to orchestrate his perfect heist by deploying Magritte imagery as his modus operandi.

The push-and-pull between concealed and revealed is always exciting in crime films. There is great excitement in witnessing the role-play of dual identities, secret personas, and shifting allegiances. There is also great entertainment in seeing something very familiar, be it a piece of pop culture or artwork, functioning as a tool to wield power and corruption. In John McTiernan’s 1999 remake of The Thomas Crown affair, Thomas Crown (Pierce Brosnan) utilises The Son of Man’s anonymity to orchestrate his perfect heist by deploying Magritte imagery as his modus operandi.

While remakes can often be contentious, the great strength in this one is how it utilises themes and concepts from the original Thomas Crown Affair and makes them unique, while toying with Surrealist imagery in the process. In the 1968 original version directed by Norman Jewison, Steve McQueen stars as the cunning businessman who steals $2 million from a Boston bank, while Faye Dunaway portrays Vicki Anderson, the insurance agent tasked with investigating the crime. The result is an incredibly stylish and sexy neo-noir filled with gorgeous cars — something that feeds into McQueen’s real-life passion for motor-racing— and fabulous fashion.

Brosnan, meanwhile, portrays Crown with a Bond-esque flourish, depicting him as a sophisticated and suave billionaire-playboy-thief, in possession of self-confidence that might verge on smarmy were it not for Brosnan’s self-awareness and vitality in the role. Crown doesn’t need to commit the crime; it’s purely for his enjoyment. What better place to steal than inside a world-renowned art gallery with a million dollars’ worth of art under one roof?

Crown is a man who will stop at nothing to get what he wants. His disposable wealth allows him to employ men to participate in a bogus offence, which, in turn, will cause a distraction enabling the billionaire to engage with the actual crime: the procurement of a single Monet painting from inside New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s a perfect strategy, as the noise on the one side enables Crown to swiftly, expertly, steal the item in broad daylight. In seconds, Crown has whipped the painting off the wall, broken off the frames, and opened up his Bond-meets-Inspector-Gadget briefcase, placing the artwork inside and folding up the case again in a deft moment of sleight of hand. As Crown emerges from the gallery, he walks past a museum poster advertising a Magritte exhibition to take his place amongst the crowd. Of course, the Son of Man as it’s chosen image. Once again, he is faceless, anonymous, one of many suited businesspeople in the city.

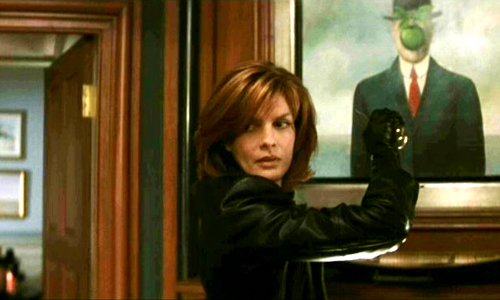

As Catherine Banning, the insurance agent sent to investigate the heist, Rene Russo is a caffeine-guzzling, no-bullshit, match for Crown, who takes matters into her own hands by bypassing the police’s too-slow methods. Banning knows the power and potency of her sexuality, and how men like Crown operate. She is introduced to us in typical femme-fatale style as the camera pans up from her black-stockinged ankle to the top of her thigh. She wields this power to her advantage, to get her man, and get her man, with the wiles to play Crown at his own game.

“A worthy adversary,” as Crown’s therapist, Faye Dunaway in a charming cameo, comments. We cannot help but link Dunaway to her role in the first film, and in many ways, this enables her to see through Crown’s antics; she knows how men like him operate having engaged with a Thomas Crown of her own. Surrealist art is filled with repetition: certain themes will be repeated, motifs will reappear, and themes will run throughout artists’ works. Dunaway is only known as The Psychiatrist — Surrealism is rooted in psychology and freedom of the unconscious mind. It was also a movement filled with men who possessed bloated egos, and women who triumphed over their muse associations. You can see how much the Psychiatrist enjoys hearing about Banning running rings around Crown with great success, stumping this infallible man.

Both Brosnan and Russo ooze confidence and self-assurance that is intoxicating to witness. It is much a game of seduction as it is between a criminal and investigator attempting to outsmart each other. You are never quite sure who is pursuing who. The result is potent chemistry between the leads that is even more powerful when you remember that both were in their forties at the time, slightly older than McQueen and Dunaway were when they played the roles. In the remake, you watch two actors who know their craft immerse themselves in their roles with stunning confidence. They appear to be enjoying themselves, this game of cat and mouse, both playing each other, to smouldering effect. Have we seen two actors, both in their mid-forties, in such a potent film since this time? By Hollywood standards, if made today, there would undoubtedly be a substantial age-gap between the leads, with the role of Russo’s character going to a younger woman, and no doubt dulling the effect of their chemistry.

At the time of filming Brosnan had already portrayed James Bond twice, first in Goldeneye in 1995, and Tomorrow Never Dies in 1997. He would again appear as Bond in The World Is Not Enough, released the same year as The Thomas Crown Affair, making his final appearance as the spy in Die Another Day in 2002. I think that this filmography is crucial to understand his impact as Crown; both are rich, charismatic charmers with panache and a roving eye. The Irish actor demonstrated a knack for delivering innuendo laced one-liners with sly humour, and whose Bond demonstrably enjoys what he is doing. Brosnan always looks like he is having a tremendous amount of fun. As Bond he could drive his car from his phone (an update on the ever popular remote-control vehicle), which would, in turn, become invisible. This penchant for gadgets certainly extends to Crown, who seamlessly channels Bond in a stylishly choreographed heist scene that utilises Brosnan’s legacy as Bond to full effect. Brosnan is essentially the faceless businessman, peeking from behind his apple to carry out his perfect heist inside the MET.

The choice of the Monet was a smart choice, revealing the film’s most potent sting. While Venice’s St Mark’s square is the apparent location in the painting, there are also buildings in the frame’s background, initially floating shapes that take a firmer outline as soon as you set your eyes on them. Like Magritte’s work, they draw you in, and we become interested in what is both visible and made hidden. This is certainly a reoccurring theme in Surrealism: the hidden is as potent as what remains on view.

The painter and writer Dorothea Tanning, for example, painted a series of doors in her self-portrait Birthday (1942): she stands by an open door, her hand on the doorknob, which reveal a never-ending series of open doors. It’s alludes to Alice in Wonderland, and we fall down the rabbit hole with her. Tanning once said, that “enigma is a very healthy thing, because it encourages the viewer to look beyond the obvious and commonplace.” Crown as a man, and as a criminal, is an enigma: he toys with images, leads us down one path, then another, and we go along with him because it is so fascinating. All of these angles make the final scene’s reveal — of the Pissaro’s paint washing away to reveal the “stolen” Monet underneath — all the more effective. It’s a trompe l’oeil, deceiving the eye, and the audience, into what they think they have and are seeing. Very similar to Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks, it brings us back to Surrealism and the visual puns the movement was always so fond of exploring.

Magritte’s habit of repeating the same figures and motifs in his painting is something that we see deployed in full effect at the film’s ending. With the final reveal, comes a gallery-wide search for Crown, dressed as Magritte’s The Son of Man, right down to the red tie and bowler hat. However, others dressed in the same manner in the gallery, making it challenging to locate Crown amongst this sea of Magrittean imagery. The painting that comes to mind here is Magritte’s 1953 painting Golconda, as identical men (in the same image) fall from the sky. There is anonymity in repetition, and in duplicity. Tricking you throughout, and toying with images and mind, Thomas Crown has committed a perfect Surrealist crime.