“Vigilante” has long been a negative word in our culture, conjuring up images of KKK riders, Dirty Harry, and the oh-so-privileged Batman. A vigilante is one who assumes the right to punish the wicked, whether or not they have earned it, and whether or not those they take down are, in fact, wicked. A typical vigilante is often one who believes they have been wronged, but have little awareness of how their victims have been wronged.

But now, all that’s changing, as women, people of color, and other members of marginalized and discriminated against communities (and their taciturn, well-armed allies) are crafting a new wave of thrillers where the oppressed get some well-earned revenge.

In the 1980s and 90s, extralegal allies could be found mainly in the pages of Andrew Vacchs’ Burke novels, featuring a gruff veteran of the Biafran War who mainly cares about saving vulnerable women and children and very large dogs. My favorite detail of the Vacchs novels: Burke runs an ad in Soldier of Fortune magazine recruiting mercenaries for the racist Rhodesian government. Those interested in learning more send a few bucks in an envelope to what they believe is the recruitment office. Instead, Burke pockets the change and uses it to fight against the very people who gave him the cash. I really hope that there’s some Antifa folks out there carrying on the legacy of scamming the hateful.

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, Burke helped many a crime victim exact their revenge, but usually his clients had at least tried (and failed) to get police assistance first before turning to a private investigator with a Very Scary Dog. The archetypal vigilante is stepping in to help the police, not to remind them of their failures. But for the new wave of vigilantes, the cops don’t even factor in, except as potential hindrances to the growing scope of their plans. While the conservative vigilante laments the power of defense attorneys and the lack of funding for increased policing, the vigilante of the oppressed knows that it is the system itself that allows villainry to go unpunished.

The oppressed have, of course, always existed in the literature of vengeance—just look at any trickster tale, or (don’t) look at any 1970s rape-and-revenge thriller. So what is the difference between vigilantism and run-of-the-mill revenge? A vigilante hunts down those they perceive as threats to their community, seeing themselves as objective enforcers of justice that cannot be achieved by other means. The revenge thriller is more intimate—vengeance is satisfying for the personal release it brings, but needs to go no further than a simple eye for an eye. And of course, likes squares and rectangles, there’s plenty of room for personal vengeance within the wider scope of the vigilante narrative. The vigilantes of the oppressed have one more thing going for them—unlike Batman, they don’t come from money, and they’re not averse to making a buck in the course of their plans.

Amy Gentry, Last Woman Standing

In Amy Gentry’s sophomore novel, Last Woman Standing, a comedian and a programmer team up to get revenge on Very Bad Men in this ode to Strangers on a Train. The programmer agrees to bump off the comedian’s foil, and vice versa, but the programmer has a larger plan than just personal vengeance. She’s going to bring technology into the game. She’s designed an app that will create a network of women in need of vengeance, executed by randomly selected other users of the site. Seems like a pretty good idea, n’est-ce pas? But of course, all goes to shambles.

Wendy Heard, The Kill Club

In another fantastic modernized take on on Strangers on a Train, Wendy Heard also takes Highsmith’s concept to its logical conclusion, this time through an anonymous network of “helpers” who take care of people’s problems for them, as long as those people give a little something back. Jazz just wants to protect her diabetic brother from a foster mother who refuses to give him his medication, but when she receives a call offering assistance, she finds herself seriously considering the offer of help, as long as she gets rid of someone else’s problem. Permanently.

David Heska Wanbli Weiden, Winter Counts

This one’s noir to the bone, even moreso because the need for a vigilante is based in real life circumstances. David Heska Wanbli Weiden’s stunning debut, Winter Counts, follows Virgil Wounded Horse, who acts as kind of enforcer for those who are caught in a legal no-man’s-land on their tribal reservation, and need some major ass-kicking on their behalf. He usually spends his days delivering beatings to pedophiles and wife-beaters and caring for his orphaned nephew, but when he reconnects with a old flame and is hired by her father to investigate an uptick of youth drug use, he finds himself tested to protect his community in a whole new way.

Layne Fargo, They Never Learn

The author thinks this one is more of a serial killer novel than a vigilante thriller, but luckily, as readers, we can place any interpretation on a text we want (hence the enduring popularity of Freudian literary criticism). I was actually inspired to write this post because of Fargo’s novel, which I adored to the max. In Layne Fargo’s sophomore crime thriller, a professor at a university eliminates one male predator from the campus per year. She’s careful to frame each act as a suicide or accident, but eventually, the number of popular male students killing themselves begins to alarm the administration, and the professor must think quickly—and dispatch of some urgent matters—before anyone can cotton on.

Halley Sutton, The Lady Upstairs

Halley Sutton follows in Vacchs’ footsteps with her politically minded scam artists, but goes much further with the concept. The Lady Upstairs features a blackmail agency staffed with beautiful workers skilled at engineering compromising situations for Hollywood Bad Men and then capturing them on video. The mysterious Lady Upstairs determines assignments and hands them out via an enigmatic intermediary. A brooding enforcer serves as a willing sex partner in the off hours, and in general, everyone is super hot and has sex with each other. In between screwing over powerful predators, of course. QUITE the satisfying thriller.

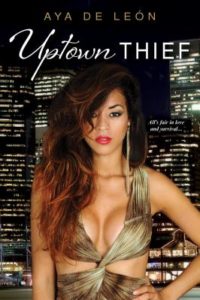

Aya de Leon’s Justice Hustler Series

Aya de Leon’s sultry and revolutionary heroines aren’t out to make money—they’re out to steal from those who have too much money, and, um, donate it to a nonprofit health clinic for sex workers. One of the taglines for the series reads: “Sometimes the best donor to a nonprofit is the unintentional donor.” They also use the money they take to support unionization efforts for sex workers and dancers, and to provide opportunities for their families and communities. And when they can’t steal from Peter to pay Paul, well, I guess they’ll have to just get rid of both. Uptown Thief, the second in the series, is the one the fits best with my theme, but the whole series is brilliant, political, and SO. MUCH. FUN.