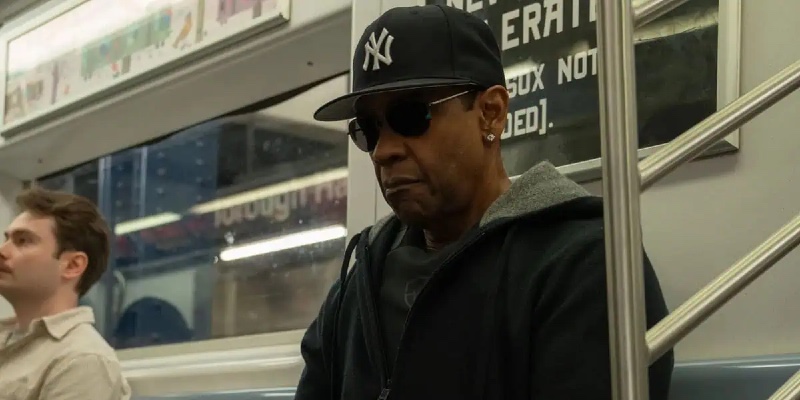

Roughly an hour into Highest 2 Lowest, the latest Spike Lee joint, the wildly successful owner of the record label “Stackin’ Hits” David King (Denzel Washington, in the duo’s fifth go-round) boards a 4-train from Brooklyn’s Borough Hall in a hoodie-ballcap-pulled-low–dark sunglasses ensemble. King is a kingmaker, a “Babyface” Edmonds/Timbaland level producer, who boards the subway incognito because he’s carrying a black Air Jordan backpack loaded up with $17.5-million in Swiss francs. He’s headed to the Bronx to pay off kidnappers who mistakenly snatched up the son of King’s chauffeur-right-hand man Paul Christopher, played with jittery stoicism by Jeffrey Wright, whose real life son Elijah, plays Kyle in a small but pivotal role as a ducktaped victim, with an ear for hip-hop, trapped in a bathtub out of the Saw franchise.

Up to this point, Highest 2 Lowest, now streaming on Apple TV, has been a slow burn as King, who would’ve spared no expense to get his own son Trey back, dithers on delivering the enormous ransom. Paying up means liquidation, jeopardizing his plan to take back full ownership of Stackin’ Hits and get the slumping label back on track. The pacing up to the train sequence is methodical: Paul begging (and Trey demanding) King do right by Kyle; The patriarch realizing his life’s work is doomed if the kidnapper is serious about killing the hostage; and the investigative unit mapping out how following the money through tracking services and undercovers will save the kid and recover the bag of currency beloved by money launderers the world over.

As the train heads north to the Boogie Down, Highest 2 Lowest inverses its name and the momentum goes to eleven. Lee choreographs a rollicking three-borough under-and-over-ground ride that sits smack dab in between The French Connection and Taking of Pelham One Two Three, the Gotham chase scene GOATS. It’s thrilling, layered-upon-layered loud kinetic energy at every stop. The car fills up with rowdy Bronx Bomber fans on their way to a Yankee Stadium matinee against the hated Red Sox. (A frighteningly amped-up in-your-face Nick Turturro was born ready for his “Boston Sucks!” close-up.) Gameday coincides with the Puerto Rican Day Parade, all soundtracked to the pulsating Latin jazz of the great Eddie Palmieri. (R.I.P. to the “Madman of Salsa.”) The kidnapper is sharp, the dropoff in all the chaos is intentional. Once the bag tumbles from the train platform, the scenes hit the streets–including the now repainted to deter touristas “Joker” stairs–and becomes a zig-zagging cross-cutting cat-and-mousing game between an armada of mopeds, a brigade of cop cruisers, and a mob of sweaty summer party people cha-cha-ing the day away.

The fascinating parallel is that the money-thrown-from-a-moving-train sequence is also the highpoint of High and Low, the underappreciated 1963 Akira Kurosawa film that Lee re-imagined and reconstituted in gilded 2025 New York City. In the black-and-white postwar Tokyo-set predecessor, it’s a Kodama #2 express train with a window that opens exactly 2.75-inches, enough space for two bags containing $25,000,000-Yen apiece–roughly $150,000 total 1963 US dollars if my math is right, doubtful–to be chucked over a bridge to a waiting kidnapper and Shinichi, the chauffeur’s son. It’s a quieter, less anarchic, but no less riveting sequence. It’s also the one that sends High and Low on a totally divergent path from Highest 2 Lowest. Or vice versa if you’re caught up in the whole Criterion chicken-or-egg thing.

Stolid by-the-book adaptations and pointless remakes–ahem, Mr. Washington–don’t do much for our shared cultural betterment, but stories that evolve over time and mediums to become their own unique thing are always worth a look. Neither Highest 2 Lowest or High to Low are peak mountaintop Lee or Kurosawa, but when the movies start cooking, they elicit glee found when one-of-a-kind filmmakers conjure on-screen magic. Only these two idiosyncratic masters could have made their respective versions. All the more intriguing given the basic story was cribbed from a pulp novel of middling renown.

Ed McBain is among the more prolific novelists in crime writing annals, penning some eighty pulps, including 55 in the “87th Precinct” series. The streak started in 1956 with Cop Hater and ended in 2005, the year he died at 78, with Fiddlers. McBain is one of a handful of writers who created and defined the mid-century American police procedural. You know, the backbone for the Law & Order, CSI and NCIS multiverse juggernauts airing on some random channel 24-hours a day since the days when pagers were sophisticated technology.

Published in 1959, King’s Ransom is the tenth in the series, and its main strength is the framework for the movies to follow. The story takes place in the city of Isola, a thinly-fictionalized Manhattan, at the estate of Douglas King, an executive at the Granger Shoe Company who started at the lowest stockboy rung and worked his way up to the highest executive suite. King has been quietly buying up stock to take over Granger. There are some business-guy shenanigans going on as King attempts his takeover, which in all three versions, is muddled and an afterthought once the criminality kicks in.

(The one fun corporate chatter exception is the livid High and Low reaction of Kingo Gondo, played by Kurosawa stalwart Toshiro Mifune, at the other executives suggestion that they eschew quality to make cheaper, crappier, oft-replaced women’s footwear in booming post-WWII Japan. The fury bubbling up as Gondo says “it’s not like a hat, shoes must carry.. A woman’s weight!” while destroying a garbage high heel is priceless.)

In King’s Ransom the kidnappers demand $500K–$5.9-million today, I think– but of course, they’ve taken the chauffeur’s boy, not King’s young scion, Billy. From here, McBain’s work becomes a parallel tale of bumbling hooligans and the lawmen working the case, but without a kick-ass midpoint motorized urban pursuit. Douglas is also a much more cynical asshole than David or Kingo. He has few qualms about sacrificing an eight-year-old boy, going so far as to explain how guilt-free and “tickled to death” he was when a fellow serviceman bought it in combat because “the bullet hadn’t clipped me.” And Billy, well as he tells his bereft wife Diane, “I don’t even like him, do you know that?”

(Speaking of Diane, King’s Ransom suffers from the B-grade misogyny of the day as “sex dripped from her curvaceous frame in bucketfuls, tubfuls, vatfuls.” I did get a juvenile chuckle at one detective’s exhortation that a fellow officer’s wife has “knockers out to here.” Ahhhh, youthful memories of Playboy jokes from lucky stashes found in the woods goneby.)

I read King’s Ransom a few weeks ago and am already fuzzy on how it wraps up. One of the kidnappers has a homemade radio device that plays a part, Billy messes around with a shotgun at one point, and Douglas almost strangles a guy to death… No matter. In the end, the kid is fine, Granger Shoe Company is under King’s control, and the squadroom cops are drinking coffee and telling dirty jokes. Outside of 87th Precinct sickos, King’s Ransom would be a forgotten dime-store diversion if not for the “we kidnapped the wrong little dude” premise that led first-time screenwriter Alan Fox to advance the story’s evolutionary journey.

“I get up really early to start writing and one morning, I’m in Los Angeles, I get a call at like 4 a.m. from a number I don’t recognize so I let it go to voicemail,” says Fox, 37. “It’s Denzel! I called him right back because he’s one of the greatest to ever do it and wants to discuss ideas at this hour? I was so excited, I had to let him know I’m also awake and on it.”

In his early 20s, Fox signed a “360 deal” with the hip-hop label Cartel Records, in which cash is advanced to the artist and in exchange, the label gets a piece of everything including merchandise, touring, publishing, media appearances, etc. Not that long ago, the label primarily took its cut from album sales, but when CDs fell off a cliff in the 2000s, the 360 deal came into being. In an ideal world, an equitable structure with binding legal protections could work for both sides, but this is the music business–the hip-hop music business, specifically–and like many other young broke artists with little recourse, Fox was pressured into signing a bad exploitative contract. He did himself no favors and his music career ended up going nowhere, except into litigation.

“I wanted to make storytelling music that was at least somewhat socially conscious, like Lupe Fiasco. I had elements of how life is now lived through our screens and fake online personas, the effects of technology and where social media was heading,” says Fox. “Cartel wasn’t having any of it, in part because I look like a boy band reject.”

In reaching out to Fox, I aimed to get the inside scoop on how a handsome white boy ended up penning a screenplay for three of America’s foremost Black artists, the third being A$AP Rocky, who plays aspiring rapper-novice kidnapper Yung Felon. (Check the infectious “Trunks”, declaring it “the song of autumn.”) What I got was so much more, as Fox’s burgeoning career is already a banging memoir in its own right.

Backing it up a few years prior, here’s his life in short order: Fox was an all-state 6’0” point guard in North Carolina whose claim to fame was beating Steph Curry’s team for the 2006 “Little Four” title. He went on to play for a spell at UNC-Greensboro, but the re-aggravation and misdiagnosis of a groin injury suffered in high school turned his hoop dream into a nightmare right quick.

“I was sort of like {former Florida Gators quarterback} Tim Tebow in that people were like, ‘I think he’s good because they keep on winning?’ but the ceiling was play overseas for a few years and maybe become a coach,” says Fox. “Instead, I became a degenerate and drank my way out of school, problems compounding upon themselves. It was my cry-me-a-river Boobie Miles story.”

Unlike the cursed star of Friday Night Lights however, Fox soon had a Lana Turner at the malt shop moment. Out of the blue, someone came up and asked if he’d ever considered becoming a model. Next thing you know, he’s living in a Miami Beach house filled with too many hot broke-ass dudes.

“It was a bleak world, an orphanage of square-jawed urchins, none of whom were on their way to becoming doctors or lawyers,” says Fox. “It was all guys like me who just wanted a way out of something, a lot of them from other countries who saw America as their salvation. Tangentially, you are part of this glowing ritzy world, but usually you’re just part of the catering staff, taking leftovers home because you can’t afford to eat.”

Fox wrote a novel based on his modeling experiences that never sold. And by 2008, was already feeling like has-been with no idea of how to put his life back together.

And then Taylor Swift came calling.

“Here I was this failed basketball player from a small southern town and then I got booked to be in the “Fifteen” video. Even back then, it was like Taylor and Jesus in the pecking order, and today, she’s somehow even bigger than social media,” says Fox. “I was just a day player for $600, but it was still such an amazing experience. Taylor was great to everyone involved, she was so friendly and clever. She was a supernova but on the shoot, we all felt like we were in the same orbit. The video brought me a lot of attention, all kinds of people from high school, college, girls I grew up with reached out. And yet I’m still in a bunk bed with another miserable model, but it was a bridge to what I loved, making music.”

Sort of. An amazing experience, but nothing gelled from it. It got him to Cartel, but since after that flopped, Fox moved to New York City and got a degree from Hunter College. Still not 30, Fox would’ve been back to square one, except his lawyer in the 360 deal fiasco represented a number of Hollywood writers and encouraged him to give it a shot. Fox didn’t really know anything about screenwriting, so he tried his hand at penning a play. On Microsoft Word. In 2019, “Safe Space,” a dark drama work about political correctness turmoil, debuted at Sag Harbor’s Bay Street Theater with Mercedes Ruehl, 1992 supporting actress Oscar-winner for The Fisher King, playing the head of a fictional elite American college.

“Safe Space” was purchased by big-time Sony Pictures executive Amy Pascal, which started Fox’s screenwriting gig in earnest. Things were finally looking up.. Until an airborne virus sent the entire planet into hibernation.

Fox took the hits. And stacked them.

It would take a few years and a handful of non-starter projects before Fox hit the jackpot. A script for a High and Low remake had been kicking around Hollywood for years. At various points Fox believed it was in the hands of David Mamet, Richard Price, Mike Nichols, Martin Scorsese and Chris Rock, among others. Be it superstition or producers’ covering-their-expensive-asses, it’s often the case that dead screenplays remain comatose. Fox saw an opportunity.

One of the first major changes he made from the McBain-Kurosawa pipeline was to kick off the shoe business and place it in a greasy world he knew, the music industry. (Ultimately, $10-million was put up to buy the option and to clear the previous iteration decks, which is why Fox has the sole screenwriting credit on Highest 2 Lowest.) He kept at it.

“Maybe I was tapped on the shoulder to take a shot at a fresh take on a script that’s been mothballed for twenty years, because I was green, but I stopped trying to rationalize anything in my life,” says Fox. “I do know that I had never seen High and Low, was hardly aware of Kurosawa, but I had a solid plot framework in place and an idea to explore, a phrase going around after Nipsey Hussle was murdered that ‘you might be done with the ‘hood, but the ‘hood isn’t done with you.’”

And then Denzel Washington came calling.

In a recent WTF with Marc Maron interview, Spike Lee said Washington called him before he even finished reading Fox’s version. Lee hadn’t realized it was eighteen long years since they last worked together—on the brilliant bank job movie Inside Man—and since neither of them is getting any younger…

Fox’s screenplay served his leading man in one major swerve from the Kurosawa version. High and Low is an oddity in that Mifune disappears an hour into the movie. The long second act is a brick-by-brick police investigation Gondo isn’t involved in. It’s intense, within the McBain structure, and he does reappear for act three, but it’s still super weird to a modern movie sensibility when the star on the poster goes AWOL.

“When you have Denzel, you have Denzel. If he leaves at the 64-minutemark, so does the audience,” says Fox with a laugh. “We’ve all seen him in the Equalizer movies. So even as a wealthy aging record producer, it works when he and Jeffrey Wright go back to their old Bronx stomping grounds to confront Yung Felon and retrieve the loot.”

Two other important Fox alterations were aging up the kidnapper and making the crime more of more personal, and in a true modern vibe, parasocial vendetta. The villain in High and Low doesn’t get much screen time until late and barely mumbles a line or two until the powerful mano-a-mano jailhouse scene. He explodes in brain-rotting rage at Gondo’s wealth, snatching Shinchi as revenge for living in squalor, looking up from his tiny shack (and from a harrowing heroin alley setting not found in Lee’s film) at the shoe maven’s literal mansion on the hill.

Yung Felon however, is at least theoretically in the same musical universe as Wright, and thinks he’s owed for having his genius denied. In his mind, payment should be rendered for the record deal he never got. He also perceives the kidnapping as a guerilla marketing strategy. He demands Wright strike while the iron and tabloid backpages are hot, because they have captured the only thing that matters in this economy, attention. The climatic two-hander scene with A$SAP and Denzel trading barbs is riotous. It’s a real kick watching the 70-year old Washington in a loosey-goosey smiling one-upmanship bout of improvised wits (hell yeah Denzel goes bar-for-bar with the “Babushka Boi”), a small battle in the generational hip-hop wars. One will remain on top–true Spike Lee heads will catch the Easter Egg where Denzel looks down from his perch on high into the famous “clockface” Damon Wayans Bamboozled apartment, the physical pinnacle of Brooklyn high life a quarter century ago–the other left with nowhere to go but down into the outer-borough muck from which he’ll never rise.

As important a role as Fox played in shaping Highest 2 Lowest, he understood when the two longtime film companions came on board that he would be in a standby plot-problem-solving-when-necessary role. As a young white man, he can’t speak to the questions of the role older successful Black artists should play in the lives of Zoomers on the come-up, and also because well… It’s freaking Lee and Washington together again.

“There’s plenty of my script in there, but of course Highest 2 Lowest was Spike-ified, as it should be. The incredible Puerto Rican Day parade was sprung from the mind of one of the greatest chroniclers of New York City in film history,” says Fox. “These guys are legends. I have zero ego about it. My job as a screenwriter is to do whatever it takes to help get a movie made. Once a point guard, always a point guard.”