I pull up in front of a complex of endless Soviet-style apartments and walk over to the immaculate traveling hardware store that is the STC van, where I am handed a white disposable jumpsuit. The packaging species the garment’s “application” as follows: Asbestos Removal, Abattoirs, Painting, Forensics, Insulation, Laboratories, Factories, Food Processing, Waste Control, Medical, Law Enforcement, Pesticide Spraying. I am also given a disposable respirator mask and a pair of blue rubber gloves. Four of Sandra’s cleaners are there: Tania, Cheryl, Lizzie, and Dylan, everyone reduced to a small cheery face sticking out of a white disposable hood. Dylan, tall and still baby-faced, hands me two at white things that look like chef hats but turn out to be shoe covers. I glance at the others to figure out how to put them on.

With our hoods up and our blue gloves on, we stand there looking like something between Smurfs and astronauts. Except for Sandra. Sandra is wearing a slim-line purple parka—ironed—with jeans and spotless white canvas sneakers. Sandra looks like she should be enjoying a Pimm’s after a walk along the beach.

Instead she leads us through the security gates, into an elevator, and up one floor to an apartment where a young woman died of a heroin overdose and lay undiscovered for two and a half weeks in the summer heat. Sandra will collect the deceased’s personal items for the family, appraise what needs to be done to rent the apartment again, and supervise the cleaning.

A man on the ground floor looks up and asks what we are doing. “Just some maintenance, darl,” Sandra reassures him, which, in its way, is the truth.

One of the cleaners unlocks the door. Sandra has a quick look inside. “Ugh. Stinks,” she says. “Right. Masks on, breathe through your mouth!” She warns everyone to watch out for syringes while helping Tania don her mask. Tightening it, Sandra says to her wryly, “You may never breathe again, but don’t worry about it.”

Cheryl takes out a small jar of Tiger Balm and rubs it into each nostril before slipping on her mask.

Sandra remains unmasked. “Been doing it for so long, I don’t bother . . . Grin and bear it!” she sings.

It is not her most visible trait—you would miss it altogether if you did not know her well, if she had not let you in sufficiently to welcome your calls with a sweetly rasping, “Good morning, my little dove”—but that is what makes it her strongest: a bodily fortitude so incredible that it cannot be ascribed to mere biology. Aside from carrying around with her a lime-colored leather handbag of fine quality in which she keeps an electric-blue tin of mints, six lipsticks, three jail-sized key rings, tissues, a camera, a little black diary for notes, a pen to write them with, a Ventolin inhaler, a mascara, a bottle of water, her iPhone, and a cord with which to recharge it, Sandra also carries the burden of lung disease so severe that she cannot take more than a few steps, however slowly, without fighting for breath. And though you will hear this struggle, and though the sound of it is excruciating (even if it doesn’t descend into one of the frequent coughing fits so powerful it seems like it will turn her inside out), she will get on top of it as quickly as possible, accept no concern or special treatment, and resume whatever activity or conversation was interrupted with such competent dexterity that, if you remember it at all, the interruption will seem as significant as one sneeze in a cold.

***

In addition to severe pulmonary disease, Sandra also has cirrhosis of the liver. The causes of her conditions are various and not susceptible to confident isolation. The chemicals she used in the early years of her cleaning business may play a role; so, too, her decades of double-dosing female hormones. Then there are viruses and biology and a factor euphemistically known as “lifestyle,” which carries with it specious overtones of culpability. Her drinking, and her years of heavy drug use earlier in her life, conform with the fact that trans people have higher rates of self-medication.

I once mentioned to her how I read that, even on the normal dose of hormones, the medical recommendation is to stay as healthy as possible through diet, exercise, and abstaining from cigarettes and alcohol. Her thoughts on this were expressed by a prolonged period of deep laughter and, as she finally dabbed at her eyes, the comment: “Fuck me, that’s a bit like a comedy routine.”

***

Sandra’s lifestyle is not what runners would call a suicide pace. On the contrary, it is deeply sustaining. “I like to keep busy,” I heard her explain to a client once. “Having a terminal illness, I find that it keeps my mind busy, I don’t think about it, and I stay positive.” She has no more chances for a lung transplant. “None at all. Signed, sealed, and delivered. How many times have they had me dead and buried? They should name me Lady Lazarus,” she laughed. I had seen for myself the months of deep depression that followed the panel’s final decision. The months when she found that the less she did, the less she wanted to do, until she was, yes, willing herself to die.

“Breathe through your mouth! Concentrate on it!” Sandra commands as she turns the doorknob and leads the charge straight ahead into the dim apartment.

The first thing I notice is the flies. Their papery corpses are crisp underfoot. I wouldn’t say that the place is carpeted with flies, but there is a pretty consistent cover of them on the tiles. It is a small apartment. The laundry cupboard is in the tiny foyer, and the dryer door is opened wide. A basket of clean clothes is on the floor beside it.

I walk past a bathroom and two small bedrooms and into a living room–kitchen area. The TV has been left on and is playing cartoons. There is a balcony at the far end of the apartment; a breeze blows in through the open sliding door and over the sofa, which has been stripped of its cover but not the person-shaped rust-red stain spread across the seat nearest the window. The stain is shocking and frightening but not as frightening as the tableau of life suddenly interrupted.

Cheryl is in the main bedroom guessing about the face of the woman whose underwear drawer she is emptying. Tania is making an inventory of the kitchen. She opens drawers and cupboards, taking photos of everything inside. The top drawer has the full complement of cooking utensils owned by high-functioning adults. The cupboard has a big box of cereal, a jar of Gatorade powder. A plastic shopping bag of trash is suspended from the handle of the cupboard under the sink.

“Everything has to go,” Sandra says, striding through.

“The fridge comes with the apartment,” Lizzie reminds her.

“Ah.” Sandra is dismayed. I watch her mentally tick through the library of disinfectants in her van. “What else comes with the apartment? We need to be clear or else we’ll throw everything out.”

***

The cleaners are quiet and efficient; quick and respectful. They remind me of nurses. Black mounds of dead flies are pooled in the light fixtures. I scan the bookshelf. There is Narcotics Anonymous. There is Secrets of Attraction. Taking Care of Yourself and Your Family and When Everything Changes, Change Everything. There are DVDs. There is Bridesmaids. An ad for Big Hugs Elmo, the toy that hugs back, comes on the TV. I go into the main bedroom.

A copy of The Instant Tarot Reader holds a piece of black fabric in place over the window near the bed. There are bottles of Ralph Lauren perfume and a pink salt lamp and an organic lip balm from Miranda Kerr’s line.

“Anything that’s personalized, anything that’s got her handwriting, her name . . . ,” Cheryl reminds Lizzie as they squat to sort through the desk at the foot of the bed. They are winding up her phone charger and putting her handbag near the front door.

Sandra instructs Dylan to take the clean syringes and seal up the yellow plastic container of dirty syringes on the coffee table for the police “as evidence of drug activity.” Although the police do not disclose investigative details to Sandra, she knows this death is not being treated as a homicide. Still, she suspects the woman was not alone when she died. “You do your own Sherlock Holmes. You play detective all day long,” she told me once.

I cross the hall. The bathroom cupboards are open. There are the usual creams and appliances. Fake tan. The same brand of exfoliator I use. I go back into the living room and force myself to look around slowly. I see two scattered bed pillows covered with the same red-brown stain as the one on the couch. Drying blood. I see a viscous smear of human shit on the floor under the couch. I see a big bottle of Diet Pepsi, still full, and a pack of cigarettes on the coffee table, also full. I do not see any living flies. The apartment is simultaneously so full and so empty; absence is a presence like dark matter and black holes.

Sandra places a birthday card with a sassy cat on it into a white trash bag full of personal items and then instructs Dylan to look carefully through all the books to see if there are any photos between the pages. The family want anything that’s personalized. It’s important.

The four small rooms are an encyclopedia of striving and struggle. The basket of clean laundry. The elliptical machine painted thick with dust. The kitchen drawer of grocery bags at the ready for reuse. The Narcotics Anonymous handbook and Secrets of Attraction. The clean syringes. The smell of death, un-noticed for two and a half weeks at the height of summer, which is seeping through my mask and into my mouth.

We step outside for a moment. There is blood on Lizzie’s gloves; redder—fresher—than the blood on the fabric of the couch. Someone asks Sandra where it came from if the house was locked up.

“Maggots,” she replies dryly. “Cycle of life. It’s quite amazing.”

While Sandra teaches Dylan how to double-bag the personal items so they don’t smell, how to wrap tape around the top in a way that is easy for the family to open, I stare across into the windows of the identical apartments surrounding us.

This is how it ends, sometimes, with strangers in gloves looking at your blood and your too-many bottles of shampoo and your now-ironic Make Positive Changes postcard of Krishna and the last TV channel you flipped to on the night you died and the way the sun hits the tree outside your bedroom window that you used to wake up looking at. This is how it ends if you are unlucky, but lucky enough to have someone like Sandra remember to go through your books for pieces of you to save before strangers move their furniture into the spots where yours used to stand.

__________________________________

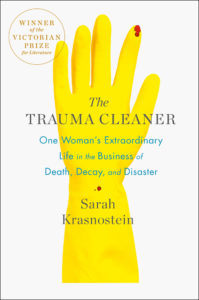

From THE TRAUMA CLEANER: One Woman’s Extraordinary Life in the Business of Death, Decay, and Disaster by Sarah Krasnostein. Copyright © 2017 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.