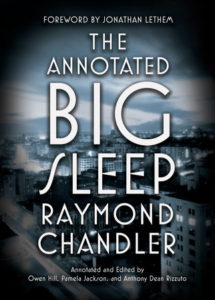

Excerpted and adapted from the editors’ introduction to The Annotated Big Sleep.

__________________________________

Raymond Chandler once wrote that “some literary antiquarian of a rather special type may one day think it worthwhile to run through the files of the pulp detective magazines” to watch as “the popular mystery story shed its refined good manners and went native.” He might have said, as the genre of detective fiction kicked out the Britishisms and became American. A chief agent of this transformation was Raymond Chandler himself. The Big Sleep was Chandler’s first novel, and it introduced the world to Philip Marlowe, the archetypal wisecracking, world-weary private detective that now occupies a permanent place in the American imagination. If Superman or John Wayne is the Zeus of American myth, and Marilyn Monroe is Aphrodite, then Marlowe is Prometheus: the noble outsider, sacrificing and enduring for a code he alone upholds.

But The Big Sleep does more than even Chandler intended it to do. Partially by design and partly by happy contingency, the novel dramatizes a cluster of profound subjects and themes, including human mortality; ethical inquiry; the sordid history of Los Angeles in the early twentieth century; the politics of class, gender, and sexuality; the explosion of Americanisms, colloquialisms, slang, and genre jargon; and a knowing playfulness with the mystery formula—all set against a backdrop of a post-Prohibition, Depression-era America teetering on the edge of World War II. For all this, The Big Sleep reads easy. And it’s a ripping good story.

In this annotated edition, we will trace the many veins of meaning folded into Chandler’s intricate novel. He didn’t think of himself as primarily a “mystery” writer—he called his stories only “ostensibly” mysteries—but consideration of his work was confined within the limitations of genre fiction during his lifetime and for decades thereafter. Chandler hated being restricted by such notions. In a late letter to publisher Hamish Hamilton he wrote: “In this country the mystery writer is looked down on as sub-literary merely because he is a mystery writer. . . . When people ask me, as occasionally they do, why I don’t try my hand at a serious novel, I don’t argue with them; I don’t even ask them what they mean by a serious novel. It would be useless. They wouldn’t know.”

Nowadays we don’t tend to be constrained by the same distinctions between “high” and “low art” that haunted Chandler. He is taught in university courses. He’s been canonized by the Library of America. Le Monde voted The Big Sleep one of the “100 Books of the Century” in 1999, and in 2005 TIME Magazine included it in its list of 100 best English-language novels since the magazine began in 1923. Before his death he would be lauded by authors as eminent W. H. Auden, Evelyn Waugh, T. S. Eliot, Graham Greene, and Christopher Isherwood. And The Big Sleep’s success moved from text to screen, with film adaptations eliciting iconic performances from two of Hollywood’s greatest leading men, Humphrey Bogart and Robert Mitchum.

***

Before the 1930s, Raymond Chandler didn’t appear to be headed for a career as a crime novelist. He wasn’t an ex-detective, like his greatest predecessor Dashiell Hammett, and there is no evidence that he associated with cops, racketeers, grifters, or the like. He was born in gritty, urban Chicago in 1888, but he spent much of his upbringing in Nebraska, England, and Ireland, and attended a good English public school, Dulwich College, where he studied languages and the classics.

After graduating, Chandler did embark on a literary career, writing reviews and poetry in a style that was a world away from “hardboiled.” Romanticism was in the air in the Edwardian England in which Chandler grew up. Retellings of the stories of the Knights of the Round Table and paintings of the knights and ladies of Arthurian England proliferated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and Chandler was unabashedly swept up in the prevailing vogue for “fairyland” and chivalry and courtly love. He later admitted that he produced fairly tepid, second-rate stuff, and he gave it up to move back to the United States in a rather aimless pursuit of an uncertain future. Amid a variety of odd jobs, he served in the Canadian Infantry in World War I. He later reflected that “once you have had to lead a platoon into direct machine-gun fire, nothing is ever the same again.” Needless to say, the world was transformed as well. Among the explosions, cultural and otherwise, the Great War blasted out of existence the prevailing predilection for nostalgic romance. In 1929, Virginia Woolf would ask where it all went, the thriving Romantic tradition of just a generation before: “Shall we lay the blame on the war? When the guns fired in August of 1914, did the faces of men and women show so plain in each other’s eyes that romance was killed?” Although the First World War, the literary Modernism it spawned, and Depression-era America seem perfectly antithetical to the Romantic tradition, certain key features of the form—especially the themes of chivalry and heroism—lay buried but alive in Chandler’s imagination. They would reappear, maimed and shell-shocked, in his first novel.

After short stints in St. Louis and San Francisco, Chandler moved to Los Angeles in 1913. Ever peripatetic, it took him six more years to settle permanently there. The city served not only as setting but in some ways as the other major character in the Philip Marlowe novels. Its character was set by its sudden expansion, and the self-promotion and greed that went with it. It was a city of excess, escapism (Hollywood!), tawdriness, exhibitionism, and corruption. In the nineteen-teens it was the fastest-growing city on earth, hyped and hustled like perhaps no other city ever had been. The population of Los Angeles ballooned threefold between 1910 and 1930, from approximately 310,000 to about 1,250,000, with the formerly barren greater L.A. County housing two and a half million. In this time, the streets were paved, automobiles replaced horse-drawn carriages and the electric railway system, and the Los Angeles Aqueduct was built to heist water from the Owens Valley 250 miles away. Corruption was rife, and politicians and law enforcement often worked in tandem with the LA “System,” the syndicate of organized crime. Los Angeles was also a city of sin, a proto-Las Vegas surfeited with prostitution and gambling. Journalist Carey McWilliams wrote that “Los Angeles is the kind of place where perversion is perverted and prostitution prostituted.” Chandler grafted this “vast melodrama of maladjustment,” as L.A. historian Richard Rayner aptly calls it, onto his fiction. This wonderfully dysfunctional backdrop beckoned many writers. Chandler would later proudly claim that before him “Los Angeles had never been written about,” but that wasn’t exactly true. Both Paul Cain and James M. Cain (no relation) had started publishing their brutally hardboiled Angelino stories in the early 1930s. Horace McCoy’s dark LA novel They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? was published in 1935. They were soon joined by Nathaniel West, whose Hollywood novel The Day of the Locust came out the same year as The Big Sleep. And Chester Himes’ critical look at race and class in Los Angeles, If He Hollers Let Him Go, would follow six years later. Mike Davis has said that LA Noir writers like Chandler, Chester Himes, and others represent an alternate public history of Los Angeles.

After arriving in Los Angeles, Chandler worked first as a bookkeeper and then as an executive for the Dabney Oil Syndicate. There he saw firsthand some of the corruption endemic to the oil industry and the justice system. He always saw his adopted hometown through the eyes of an outsider. In 1950 he would reflect, “I arrived in California with a beautiful wardrobe, a public school accent, no practical gifts for earning a living, and a contempt for the natives that, I am sorry to say, persists to this day.”

“I arrived in California with a beautiful wardrobe, a public school accent, no practical gifts for earning a living, and a contempt for the natives that, I am sorry to say, persists to this day.”Chandler was a successful executive in the oil industry as the Depression hit in 1929 and deepened in the following years. When he was sacked by Dabney Oil in 1931, it wasn’t because of the wider economic collapse, nor because he was “intrigued” out of the job, as he later averred, but because of unacceptable behavior and too many lost weekends. (See the note to Marlowe’s firing in Chapter Two of the novel). Finding himself out of work at the age of forty-three, two years into the Great Depression, it seemed that Chandler was in for hard times.

Chandler took it as an opportunity to do “what I had always wanted to do—write.” But he had to find a way to make it pay. He later recalled, “In 1931 my wife and I used to cruise up and down the Pacific Coast in a very leisurely way, and at night, just to have something to read, I would pick a pulp magazine off the rack. It suddenly struck me that I might be able to write this stuff and get paid while I was learning.” He never underestimated his chosen task. After the publication of his first story in December 1933 he wrote to friend William Lever, “It took me a year to write my first story. I had to go back to the beginning and learn to write all over again.”

***

The pulp magazines (so called because they were printed cheaply on wood-pulp paper) were ubiquitous at newsstands, bus stations, and drugstores. They were a cheap, gaudy source of popular entertainment that sometimes mixed in subversive social commentary with tales of adventure and derring-do. The format, invented in 1882 as a vehicle for children’s adventure stories, was tremendously popular when Chandler was growing up. By the 1920s there were pulps specializing in each popular sub-genre: detective stories, westerns, love stories, adventure stories, sea stories, stories of the occult, and so on. During the Depression these sources of cheap entertainment provided vital escape for the downtrodden and disenfranchised.

Black Mask was widely regarded as the best of the bunch. It was founded in 1920 by drama critic and editor George Nathan and journalist, culture maven, and scholar H.L. Mencken as way to fund their tonier magazine, The Smart Set. Its early subtitle announced “Western, Detective, and Adventure Stories,” but due to popular demand the crime stories—and specifically the newly-invented “hard-boiled” detective fiction—took over.

Hardboiled fiction was a revolutionary change in the mystery genre. Edgar Allen Poe generally receives the credit for inventing detective fiction (which he called “tales of ratiocination,” meaning, generally, stories of rational deduction) in three short stories in the 1840s starring the eccentric genius Auguste Dupin. Arthur Conan Doyle followed Poe’s lead when he invented his own brilliantly eccentric hero named Sherlock Holmes in 1887. Early twentieth-century crime fiction generally fell in step behind Poe and Doyle, giving us genteel amateurs like Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, Dorothy Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey, and the estimable Ellery Queen. The stories were often “puzzle mysteries” or “whodunits” where the reader played along with the detective to interpret the clues and solve the mystery. One of these authors, S.S. Van Dine (the pseudonym of American art critic Willard Huntington Wright), even published the rules for this type of literary game in his 1928 essay “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories.” (Rule number one: “The reader must have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery. All clues must be plainly stated and described.” Just try this with The Big Sleep!)

This is now considered the Golden Age of detective fiction. Chandler and his fellow hardboiled practitioners roundly rejected this legacy. When Chandler has Philip Marlowe trenchantly declare that “I’m not Sherlock Holmes or [Van Dine’s] Philo Vance” in Chapter Thirty of The Big Sleep, he’s making a statement as much about the genre that Marlowe is playing in as about the kind of detective Marlowe is. Chandler’s powerful manifestos on behalf of the American hardboiled rejection of “drawing-room mysteries” can be found in two key essays: his magnificent 1944 essay “The Simple Art of Murder,” and the introduction to Trouble Is My Business, with which we began our own introduction.

Black Mask and other hardboiled pulps like Dime Detective and Detective Weekly cut a new path. John Carroll Daly broke in the hardboiled style with his story “The False Burton Combs” in 1922; his success was enormous, and he was emulated by Black Mask writers throughout the decade. The style was less a continuation of the existing tradition of detective fiction than a critical reaction to the corruption and excesses of the 1920s and a stylized representation of the organized crime networks spawned by Prohibition. This social context gave rise to a widespread popular demand for crime-related stories in all forms: print, movies, word of mouth, newsreels, gangster films, true-crime journalism, novels, short stories—you name it. As Luc Sante puts it, “the art of lawlessness began a major upward trend all over the world” at this time.

Hardboiled captured the violence of the twenties and the desperation of the thirties in substance, and displayed them formally in a brutal, clipped, but—in the case of Hammett and Chandler, at least—distinctly poetic style.Hardboiled, as a subgenre, is infamously “American.” To recall Chandler’s terms: it is the mystery going native. Hardboiled captured the violence of the twenties and the desperation of the thirties in substance, and displayed them formally in a brutal, clipped, but—in the case of Hammett and Chandler, at least—distinctly poetic style. The phrase “hard-boiled” is itself an Americanism. According to Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, to be “hard-boiled” is to be “one who is toughened by experience; a person with no illusions or sentimentalities.” In the eloquent words of mystery novelist Walter Mosley, the hardboiled style is “elegant and concise language used to describe an ugly and possibly irredeemable world,” a style which captivates us “the way a bright and shiny stainless-steel garbage can houses maggots and rats.” As Mosley indicates, the world according to hardboiled is not only tough but vibrant: a gritty, profoundly urban setting teeming with underworld life—booze, sex, drugs, violence—and the decadence of the wealthy and powerful. Hammett elevated the form in a series of stories in the first half of the twenties, but truly revolutionized it with his novels Red Harvest, The Dain Curse, and The Maltese Falcon (all first serialized in Black Mask between 1927 and 1929).

Hammett and Black Mask editor Joseph Shaw derived a literary program to lend psychological and linguistic realism, not to mention literary status, to what was becoming a very formulaic, “lowbrow” form. Toward this end, Hammett mixed hardboiled with Hemingway—shaken, not stirred. For Chandler, as for Hammett, Hemingway was “the greatest living American novelist.” Hemingway’s 1926 The Sun Also Rises became the hardboiled touchstone, with its interior monologue, stark prose, and colloquial turns of phrase. “It is awfully easy to be hard-boiled about everything in the daytime,” protagonist Jake Barnes reflects, “but at night it is another thing.” (It’s tempting to consider Hemingway’s characters’ drunken quest for hard-boiled eggs a literary in-joke.)

In the “Simple Art of Murder,” Chandler establishes the genealogy of the form that he chose to work in. He links Hammett back to Hemingway, but Hemingway back to Theodore Dreiser, Carl Sandburg, and Ring Lardner—the sinewy tradition of the American literary vernacular mixed with social and psychological realism, which itself grew out of the nineteenth-century Naturalist movement. The key figures here are Frank Norris, especially for subject matter, and Stephen Crane, for substance and style. Norris wrote on corruption and greed among economic forces in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and Crane, generally underestimated as one of the influences in this context (and one of Hemingway’s greatest early influences) was the author of taut, ironic tales of impending violence. In “Simple Art,” Chandler calls this realistic style a “revolutionary debunking of both the language and the material of fiction.” “You can take it clear back to Walt Whitman if you like,” Chandler says—and probably further back than that, in England anyway, to Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, which famously announced a turn to “real language of men” in its Preface/manifesto of 1800. “It probably started in poetry,” Chandler says coyly; “almost everything does.”

If, for Hammett, the most important work was Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926), then for Chandler it was Hammett’s Maltese Falcon (1930). Yet for all their similarities—and we will note several places where Chandler overlaps with, and even lifts from Hammett, during the course of The Big Sleep—they are profoundly different. Chandler, coming after, can take Hammett’s realism and use of the vernacular à la Hemingway as given. He adds two crucial components that make him distinct: a dose of idealism and a strong strain of humor. Another key difference is between Hammett’s San Francisco and Chandler’s Los Angeles. For all their differences, Chandler made clear that Hammett paved the way for him. “I give him everything,” he wrote to Blanche Knopf in 1942.

***

Chandler became a regular contributor to the pulps beginning in 1933 with a short story called “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot.” “You’ll laugh when I tell you what I write,” he wrote William Lever shortly thereafter. “Me, with my romantic and poetical instincts. I’m writing sensational detective fiction.” He took the form seriously enough himself to thoroughly study and practice the craft of the Black Mask contributors, especially Hammett and Erle Stanley Gardner. He later wrote to Gardner, “I learned to write a novelette of one of yours about a man named Rex Kane. I simply made an extremely detailed synopsis of your story and from that rewrote it and compared what I had with yours, and then went back and rewrote it some more, and so on. It looked pretty good.” His stories were often featured on the lurid covers of Black Mask. They helped Chandler master the form and, crucially, build an audience as a crime writer.

By the late ‘30s, Chandler was ready to take on the novel form. In writing the full-length work Chandler undertook an extraordinary series of “cannibalizations” (his term), combining the plots of two of his Black Mask stories, “The Curtain” (1936) and “Killer in the Rain” (1935), adding a couple of scenes from a third, “Finger Man” (1934), and borrowing bits and pieces from other stories along the way. We provide extracts from these early stories in our notes so that the reader may see not just how extensively Chandler borrowed from himself, but also how carefully he rewrote and what he added (sometimes by subtraction) in the revision process. It’s tempting to compare Chandler’s method with Modernist exemplars like T. S. Eliot in his Waste Land and William Burroughs with his notorious cut-ups, although the effect is quite different. Chandler didn’t intend to disorient the reader or to break apart the conventional flow of narrative. Nonetheless, it was a significant way to work if only because it resulted in an emphasis on individual scenes over a seamlessly woven plot. His meticulous revision process shows also in the clipped, taut feel of the novel’s prose. By the time he was done, The Big Sleep was painstakingly polished, sleek, and streamlined. “I am a fellow who writes 30,000 words to turn in five,” he wrote in 1944. He had also invented a new name and provided a fuller psyche for his central character, who had had various names before (Mallory, Carmady, Dalmas), but now for the first time went by the name “Philip Marlowe.”

Chandler, writing to Alfred A. Knopf, remarked that “I have seen four notices, but two of them seemed more occupied with the depravity and unpleasantness of the book than with anything else.”The original cloth-bound novel sold about ten thousand copies for Knopf, in two print runs of five thousand apiece. Though this did not make it a bestseller, it did out-pace the average mystery novel, which sold about three thousand copies in cloth. Reviews were generally favorable but most were of the “round-up” type, paired with other new mystery releases in a single review. Chandler, writing to Alfred A. Knopf, remarked that “I have seen four notices, but two of them seemed more occupied with the depravity and unpleasantness of the book than with anything else.” Despite commercial success, Chandler was, in his word, “deflated” by the lack of serious attention. The Cleveland Plain Dealer, for example, published the kind of review that Chandler hated, noting the high points and asking, “What more do you want for your two bucks?” After the second cloth edition, Grosset and Dunlap brought out a discounted edition that sold another three and a half thousand copies. The first paperback edition was brought out by Avon Books in 1943: “A $2.00 MYSTERY for 25c.” It quickly sold 300,000 copies and turned Chandler’s fortunes around.

In the same year as the Avon pocketbook smash, Chandler went to work with Billy Wilder on the screenplay to James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity. After it was released by Paramount Studios the following year, it was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Screenplay. Chandler later derided the experience (“It was an agonizing experience and has probably shortened my life”), but it cemented his demand in Hollywood. By the time of the Howard Hawks filmed version of TBS in 1946, Chandler was an established name in Hollywood and in mystery novel circles. But he never shook the feeling that his true literary potential had gone unfulfilled. A few years before his death in 1959, Chandler declared to an interviewer from the London Times, “I’m not going to write the great American novel.” We think he already had.

__________________________________

From the introduction to THE ANNOTATED BIG SLEEP by Raymond Chandler, Annotated and Edited by Owen Hill, Pamela Jackson, and Anthony Dean Rizzuto. Introduction copyright © 2018 by Owen Hill, Pamela Jackson, and Anthony Dean Rizzuto. To be published by Vintage Anchor Publishing, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.