Ever since humans have huddled around campfires for warmth, there have been ghost stories to rattle our bones.

Ghostly tales of our unquiet ancestors can be found in every culture across the globe—from the Onryō or vengeance spirit of Japan, to the spectral Grey Lady of the British Isles, and to the Latin American wailing woman, La Llorona—it seems there are more than enough spooks to go around the globe.

As we moved from our caves and open plains and built great cities to colonize, it seems our ghosts travelled with us and into our homes. Henry James’ 1898 novella The Turn of the Screw placed the haunting in the hearts of the children, whose governess is driven to the edge of madness by the idea that her young charges might be possessed by unclean spirits. The 1950s gave us The Haunting of Hill House, in which Shirley Jackson described the titular building as being, “Not sane.” The 1970s were dominated by the domestic terrors of the Amityville Horror and Enfield Poltergeist, with ensuing screams of terror heard from opposite sides of the pond. And who could hope to forget the horrible realization that property developers only moved the headstones (but not the bodies!) in Tobe Hooper’s 1980s chiller Poltergeist?

But how can ghosts continue to haunt us in our 21st century world? Surely we can’t be subject to hauntings in our modern, networked homes? How can we possibly be afraid of anything when a friendly face is just a click of an app away? Perhaps it’s that modern complacency about our safe spaces that gives ghost stories their enduring edge. Each new generation, however technologically advanced and scientifically savvy, is still subject to some sin from the past committed by our forebears. We keep pushing forward and pioneering, but we are doomed to glance back over our shoulders and into the shadows of the past.

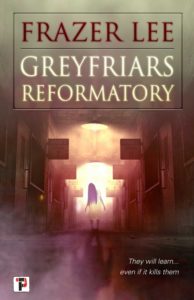

The collision of past guilt and present haunting is a core theme of my new horror novel Greyfriars Reformatory. Protagonist Emily is institutionalized at an experimental facility under the dubious care of the icy Principal Quick. Emily has vague recollections of having been to the reformatory before and, as such, is haunted by past events that she can’t quite remember. A major source of the fear in the novel is the isolation—not just the setting, but being cut off from the virtual world. After all, what nineteen year old wouldn’t find it terrifying to have no phone, and no internet, at her fingertips? Our reliance on technology has made us vulnerable when it is taken away from us. And if it becomes usurped by external forces, we are utterly helpless.

Modern ghost stories, rather than being exposed as bunkum by technology, have instead utilised that technology to create new sources of terror. Our baby monitors, camera phones, and laptop webcams have of course given us a window on a secure and happy world. But they have also provided the ghosts with a way in. Just in the same way that Shirley Jackson’s paranormal investigators found themselves possessed by the evil in Hill House, our need to connect with each other is now providing fertile ground for the ghosts to emerge. Poltergeist’s entry point for evil was the TV set in the corner of every living room, swiftly followed by Stephen Volk’s Ghostwatch (1992), which made us afraid to watch live TV broadcasts ever again. Koji Suzuki capitalised on this burgeoning techno-fear with vengeful Sadako Yamamura’s cursed videotape in his Ring series of novels (1991-2013) haunting VCRs across Japan—and beyond. Cameras were not to be trusted, as evidenced in the creepy movies Shutter (2004) and cellphones weren’t safe from hauntings either, as witnessed in One Missed Call (2003). In the supposed safety of our bedrooms, the night-vision camera footage from the Paranormal Activity series (2007-2015) gave new meaning to the old familiar refrain of, “They’re heeeeere.”

And, as the world wide web was switched on, we inadvertently unleashed a perfect storm of viral terrors. Social media has given rise to new anxieties as we await each new like and comment, increasingly hungry for attention, and confirmation. Scary stories such as Pulse (2001), my own novel and screenplay Panic Button (2011), and subsequent scary screencast horrors like Unfriended (2014) capitalise on that underlying paranoia in order to remind us that the virtual world can be just as terrifying, if not more so, than anything in the real one. Vengeful ghosts, in the tradition of Susan Hill’s character The Woman in Black (1983), are no longer confined to haunt the corridors of crumbling old houses. All they need to scare us now is a Wi-Fi connection.

In our current COVID-19 context, ghosts and hauntings have continued to have something of a field day. Alone in our rooms we have been forced to reach out on videoconferencing platforms such as Zoom, which the 2020 smash hit Shudder movie Host uses to haunting effect when a group of friends decide to alleviate the boredom of lockdown by hosting an online séance. This demonic ghost story, told in real time and in just under an hour, epitomizes how ghosts will never stop finding a way in to our lives.

However safe we feel, it seems it is only a matter of time before we look over our shoulders again—and find ourselves utterly haunted.

***